#TBT Jenny Caribbean 1500 for Philip Watch

Today we’ll take a look at a significant watch in the history of dive watches: the Jenny Caribbean 1500. Just to clear the air preemptively, the name on the dial states “Philip Watch”, but as I’ll touch upon later, Jenny did build the watch. Perhaps innovation was easier in the 1960’s because the market was comparatively wide open and hungry, but with the Caribbean, we shall see how David actually stood up to the Goliaths of the era. #TBT is here and it’s time to go deep!

The Jenny Caribbean 1500 is from the family of the first commerically available 1000M divers

Jenny (as always said, pronounced like “Yenny” and not like the character in Forest Gump) was founded in Switzerland in 1963 and basically focused on dive watches. While a 700M model was released at first, the Caribbean 1000M, Ref.702, came soon thereafter. It was closely followed by the watch you see here, the slightly rarer and larger (by 2mm) Jenny Caribbean 1500, Ref.715. It’s a bit of a debate within some forums as to whether Jenny or Aquastar offered the world’s first 1000M dive watch in 1964, but most people side with Jenny.

It’s interesting to think today that a relative “nobody” in the watch industry in the 1960’s debuted the first 1000M watch. At the time, work was underway on the future Rolex Seadweller, but 300M was really the standard for a deep diver. Listing all the watches available today that can safely reach massive depths would probably fill a book, but I do think it’s cool that the Jenny Caribbean 1500 is closely related to the first. So, how did Jenny achieve this and what else did they invent?

First of all, the Jenny Caribbean 1500 is a front-loader (for photos, see this great article), which simply means that there’s no caseback and, in turn, one less seal to be breached under water. This design was complemented by a set of no less than 3 different gaskets between the crystal and case. Speaking of the crystal, it’s a 5mm (!!) thick piece of acrylic that barely domes above the case. The other water-sealing device employed is a screw-down crown.

An Iconic Decompression Bezel

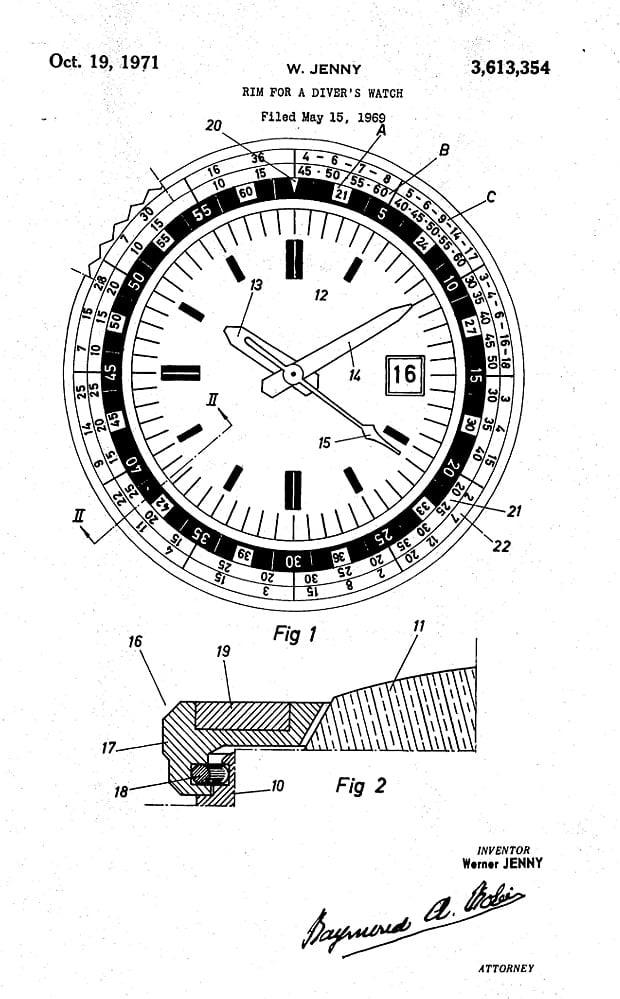

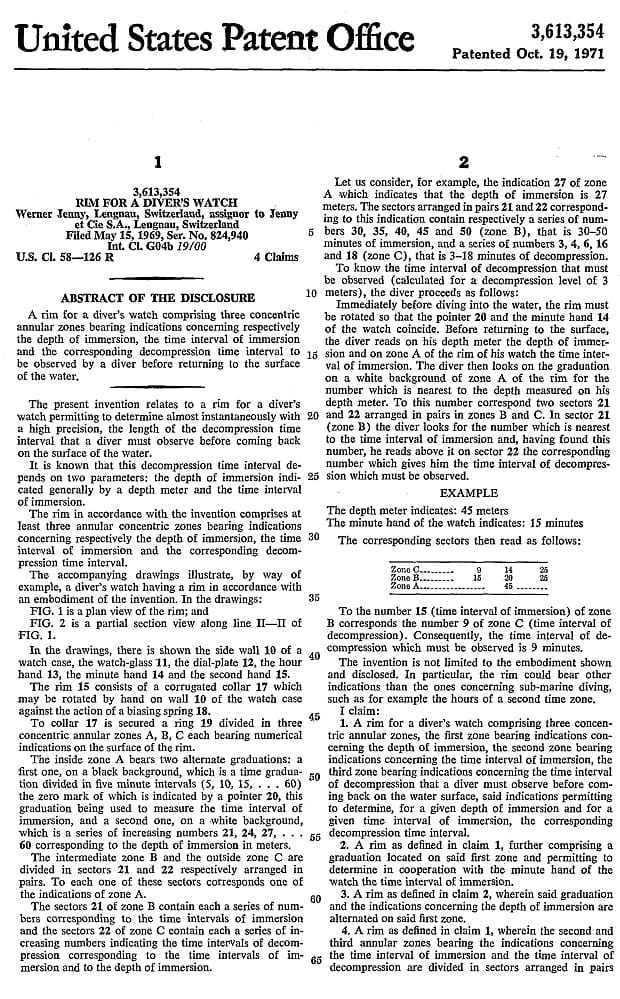

My online searches on “first 1000m dive watch” actually gathered relatively little information. However, when I started looking under “Jenny Caribbean 1000”, the thing that almost always came up was the iconic bezel. When I initially purchased the piece you see before you, I shot a picture to Jason Heaton as he seems to like crusty old dive-related gear. Sure enough, he’s a fan of the Jenny, but he did ask about how to use the crazy bezel. So, I searched and the official Jenny website gives an explanation via its original 1971 U.S. patent filing. I’m not sure what’s happened to legalese since the 1970’s, but the patent filing is incredibly clear and easy to understand. The bezel, as it turns out, is actually quite easy to use and the three concentric rings are used when the diver knows the amount of time under water and the depth. The ring then helps determine the amount of decompression time necessary.

I’m not finished with the bezel yet! The bezel of the Jenny Caribbean 1000, while absolutely stunning detail wise, is a bit curious. First, it’s nicely detailed, but the numbers are extremely small. I’m not a diver, but I have read enough stories about clarity and brightness at depth once the sunlight peters out and this tool strikes me as something very difficult to use at depth. Also, the innermost ring shows a “60” within a blue box. This refers to a depth of 60M, which is the maximum that the ring can calculate. So, I am sure that a more experienced diver will help with this, but unless calculating decompression stops are linear, this suggests that the tool really couldn’t be used below the depth of 60M. I also get that humans really aren’t and weren’t diving much below this depth, but I come back to deep diving in the early 1960’s when divers were basically breathing normal air. Prior to the use of what is known as “tri-mix” (replacing some nitrogen content with helium), divers often suffered narcosis at depth. Here again, reading the bezel of the Jenny at depths of 60M would have been difficult at best, but I’d guess that diving at these depths was and is quite dangerous no matter the tools employed.

We’re also faced with the question of why a company wanted to make a dive watch capable of 1000M. The answer is probably the same as today and that means “because they could”. I’d guess that when the Jenny Caribbean 1500 was released, dive watches capable of a stated 150M were even questionable reliability-wise. Therefore, the claim of 1000M of water resistance was likely produced to give divers that ultimate sense of security and also to show the engineering and quality capabilities of the manufacturer.

The Jenny Caribbean 1000 Details

Still with me? Now that we’ve taken a look at some of the most notable technical characteristics of the Jenny Caribbean 1000, let’s talk about the watch itself. At first glance, the Jenny looks like a typical dive watch at 40mm and in stainless steel, but a view from the side reveals a very thick, 16mm case. Credit the thick crystal for contributing to this. Another distinctive feature is the lug design. The lugs are angled on the inside and this requires, if a bracelet is fitted, some rather uniquely shaped endlinks if a flush fit is desired. I checked on eBay and it seems that someone markets period beads-of-rice bracelets to fit this case. Otherwise, a 20mm strap looks pretty good.

Moving on, the Jenny Caribbean 1500 contains a nice case and while they did beat Rolex to the bunch with a seriously deep, commercially available, diver, no one would mistake the finishing on this watch for a piece coming from “the crown”. The case contains matte surfacing on its sides, rougher lines on top and what I’d call some questionable finishing where the sides of the case meet the bezel. It also contains a large pointed crown with the Jenny “fish” logo on it. Action on unscrewing the crown is what I’d call a bit tough. It’s not overly precise and has a little lateral slop once extended, but it does the job and might be a bit stodgy from sitting for so long. The case back contains a lot of information such as the water resistance and the Swiss “Brevet” patent numbers.

Bracelet wise, this Jenny Caribbean 1500 as made for Philip Watch contains a very period-esque attachment. It’s cuff like with large plates instead of smaller links. Adjustment wise, there’s little work with here aside from the micro-adjust on the snapping clasp and at its tightest, it just fits me. Unfortunately, the links are a little thick for the clasp and it makes fastening the bracelet difficult. It’s a neat, heavy, and very original bracelet, but I may have to spring for a beads-of-rice bracelet in order to provide a better fit.

A Sparkling Dial

Returning to the dial of this watch, Philip Watch chose, or Jenny offered, a really novel look for this watch. The version you see here, in blue (it was also offered in yellow, orange, and perhaps other colors) contains what looks like metallic flake on the dial. It’s an amazing surface that some refer to as “Scotchlite” but, to me, it reminds me of 1960’s/70’s hot rods. Whatever it’s called, it’s definitely striking and in the right light, which is difficult to catch in photographs, it’s positively dazzling. Otherwise, the design is simple with white font, white lumed hands, white markers and date wheel. It’s different than anything else I own and reminds me somewhat of the colorful Squales from the same era.

ETA’s First High Beat Movement

Inside the Jenny Caribbean 1500 lies the ETA 2724. The “HI-SWING” as noted on the dial of the watch actually refers to the fact that this movement is a high frequency automatic. In fact, adding to the innovation of the piece, it was ETA’s first high frequency movement and it runs at 28,800 bph. The movement’s brief production run from 1969-1972 also helps give us some relative indication of when this watch was produced. It’s a nice movement as it features a quickset date and has a power reserve of 42 hours. My experience shows it to be an accurate runner as well.

Many Brands Used the Jenny Case

The Jenny Caribbean 1500 is principallyfound as a Jenny or a Philip Watch. It’s smaller relative, the 1000 can be found under many brand names much like watches made by Squale and Aquastar. The 1500 had what seems like a relatively short production run as noted by its movement and this in contrast to the 1000 with its relatively long production beginning in roughly 1963 and lasting until the early 1980’s. As this great article on an early Ollech & Wajs Caribbean 1000 shows, there were variations in movement, dial, hands, and even bezel with some brands opting for a standard diver’s 1-60. Pricing is really all over the map with pieces starting at roughly $800 and topping at roughly $1800. I’ve not seen a huge difference in pricing versus the 1000 or the 1500 but I’m sure sellers would try to tout the rarity of the larger model. Parts aren’t the easiest on these watches if we start with the bezels. The inlays are bakelite and while a plastic bottle may last for a gazillion years in a landfill, plastic bezels seem to exhibit the opposite behavior. They’re brittle and very hard to find. The positive is that the movements employed on the entire series of watches are highly serviceable once your watchmaker opens the front.

I bought the Jenny Caribbean 1500 because I always wanted one. The bezel fascinated me and this was before I even knew about the historical significance of this watch. The dial makes it a real standout and far different than other divers I own. As mentioned, it’s fascinating that such a small company could introduce such an innovative piece. If you’re a fan of early dive watches, the Jenny is a truly affordable and important piece to consider. Until next week….