A Brief History of Time: Audemars Piguet’s Complete Brand History — Part Two: 1968–2021

Welcome back to another installment of A Brief History of Time: Audemars Piguet. When I left you, it was 1967. Haute horology honchos Jaeger-LeCoultre, Audemars Piguet, Vacheron Constantin, and Patek Philippe, had just developed the thinnest centrally wound automatic movements. Known by Audemars Piguet as calibers 2120 and 2121, these movements were the next level of both elegance and reliability. It was this combination of refinement and robustness that would not only ensure the calibers’ 54-year production run but also place them at the heart of some of the most game-changing, iconic watches of all time. Before that could happen, however, the watch world would need a good shakeup.

And a good shakeup it received. On Christmas Day in 1969, Seiko released its first quartz watch, the Astron. Although it was gold and sold for 450,000 yen (the price of popular cars at the time), the battery-powered movement inside of it was virtually shockproof and accurate to +/-5 seconds per month. This was not just groundbreaking, but also futuristic. Even the name, “ASTRON”, sounded futuristic (as most things ending with “-tron” tend to do). Following its release, Seiko divulged many of the secrets behind its quartz patents, allowing and even encouraging competition. Quartz quickly became not only easy and quick to produce, but cheap. This changed the way the public thought about watches. No longer would a watch need to be expensive to be accurate. No longer would centuries-old traditions and skilled craftsmen be necessary to tell the time. Quartz was the future.

And the future beckoned

Asian watch manufacturers were quick to adopt quartz technology. The Swiss, however, extremely reluctant to relinquish their traditions, were left to watch their horological empire crumble. With the demands of worldwide markets rapidly changing, many Swiss brands either would not or could not keep up. By 1971, Audemars Piguet realized it needed a new strategy. The night before the Basel Watch Fair, managing director Georges Golay surveyed the brand’s offerings. He came to the sobering realization that there was nothing in its lineup that could offer what the market wanted. Despite all of its past achievements, if something didn’t change, there would be no place left for Audemars Piguet. So the brand, with a track record of pushing boundaries, decided to forge its place.

Golay had heard rumors that the Italian market was expecting an “unprecedented steel watch.” It needed to be not only masterfully finished, but also suitable for any occasion. Golay called Gérald Genta. A blossoming watch designer who had cut his teeth in the industry designing the Universal Geneve Polerouter, the Patek Philippe Golden Ellipse, and the 1959 refresh of the Omega Constellation. After relaying his demands, Golay gave the designer just one night to rise to the challenge. And rise to the challenge he did. The next day, Audemars Piguet displayed the sketches of the watch that would shake the industry to its core: the Royal Oak.

The birth of a legend

Prototyped and developed in time for Basel 1972, the Royal Oak reference 5402 was a kick in the throat to industry standards. Not only was it “jumbo” at 39mm, but it was also angular in form, highly complex in finishing, and most importantly, STEEL. A high horology timepiece from one of the world’s most prestigious manufactures, produced in such a pedestrian metal? It was utter blasphemy. Nevertheless, Audemars Piguet owned its resolve. Placing their pride-and-joy ultra-thin caliber 2121 at its heart, Audemars Piguet priced the Royal Oak at 3300 Swiss francs. That was higher than a time-only gold Patek Philippe. It was ten times the price of a Rolex Submariner. And yet, they didn’t even bother to “hide the screws.” Everything about it left the watch world aghast.

The Royal Oak was by no means an overnight success. On the contrary, it would take Audemars Piguet a full three years to sell the first 1000 pieces. Historically a stylistic influencer, however, the brand doubled down on its message: steel and status were, in fact, not polar opposites. By 1975, its persistence paid off, and the message began to stick. That year, Girard Perregaux released the Laureato, which also featured an octagonal bezel, an integrated bracelet, and a very similarly engraved dial. A year later, Patek Philippe released what would become its own steel Genta-designed icon, the Nautilus. It used the same movement as the Royal Oak, doing duty as Patek’s caliber 28-255. As more brands followed suit, the outcome was clear. The Royal Oak had not just spawned a new genre of steel luxury sports watch, no. It had made luxury watches, mechanical watches, desirable again.

Dipping its toe into the quartz pool

This did not mean, however, that Audemars Piguet was too proud to experiment with quartz at all. Backtrack a bit to 1974, and you’ll find the quartz-powered reference 6001. While inspired by the design of the Royal Oak, with a blue tapisserie dial and integrated bracelet, it is distinguished by its unique elongated octagonal case, the lack of screws on the bezel, and the rectangular brick-style bracelet links. The movement, a Swiss-made Beta 21 quartz caliber, was developed by some of the biggest players in the Swiss watch industry. It was the most accurate Swiss movement at the time, with some claiming precision as good as +/-1 second per month. This variance was easily corrected with an inset friction pusher located next to the crown. The watch was available in stainless steel, yellow gold, or white gold.

And simply because the first Royal Oak reference 5402 was released in stainless steel, it did not mean Audemars Piguet was too stubborn to utilize other materials. Ironically, the first Royal Oak ever sold (to the Shah of Iran, no less) was specially produced in white gold. By the late 1970s, AP released both two-tone and solid gold variants of the Royal Oak 5402. It was clear that the aesthetics of the Royal Oak had transcended its original medium of execution. Thus, the model became a strong foundation on which to experiment. Quartz calibers also found their way into the Royal Oak line as well. The watch became an icon of style and luxury with a multitude of variants for any taste. Despite its immense popularity, however, the Royal Oak is actually not the model the brand credits with its survival.

Remaining true to Audemars Piguet tradition

That watch, released in 1978, was the reference 5548, the world’s thinnest perpetual calendar wristwatch. At just 7mm in total thickness, it utilized the same ultra-thin base movement from the Royal Oak, with an in-house developed perpetual calendar module. The entire movement itself measured just 3.95mm thick. It sat in a 36mm gold case with a white lacquer dial, which was quite cleanly set up despite its four sub-dials. The 5548 cost roughly four times the price of the Royal Oak, but it was an instant hit. While AP produced 2,183 examples in its 14-year run, it sold as many as 400 per year at its peak. With this record-setting timepiece, in the midst of the quartz crisis, Audemars Piguet would proudly and elegantly proclaim a future for not just mechanical watches, but expensive, complicated ones.

In 1986, Audemars Piguet set another record with the release of the thinnest automatic tourbillon. The final watch, just 4.8mm in thickness, was absolutely remarkable. Its tourbillon carriage was not only the smallest ever made, at just 7.2mm, but it was also the world’s first titanium one. Non-traditional in its design, the movement was actually completely one with the watch itself. With the case back functioning as the top plate, jewels for the gear train and winding system were actually set into the case back itself and visible from the outside. Rather than a rotor, an arc-swinging hammer wound the watch, with its movement visible through the aperture at six o’clock. Other than the dial, crystal, and strap, the watch was entirely movement. Collectors today refer to this watch as simply “caliber 2870.” For an in-depth look at this fascinating watch, check out this article on TimeZone.

Wandering hours

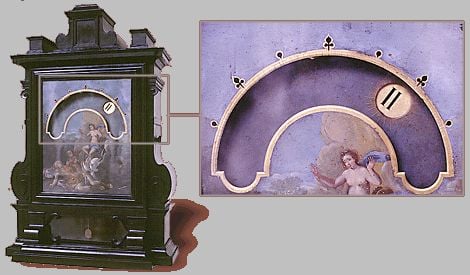

In 1991, Audemars Piguet released the Star Wheel. This watch was responsible for reviving the wandering hours display in modern horology. First designed in the 1650s for a night clock commissioned by Pope Alexander VII, the wandering hours display did away with the traditional hour hand, replacing it with a rotating disc. This disc, with numerals indicating the hours visible through an aperture on the dial, arced along a semicircular minute indicator. In the 17th century, the display was illuminated with an oil lamp, and as it was concentrated in one area rather than a whole dial, it was easy to read in the dark.

Audemars Piguet recognized the beauty in the mechanics of this unconventional display. The brand was not content, however, to hide it behind a dial. Thus, AP mounted three clear sapphire discs atop the dial on star-shaped wheels and connected them to a rotating cage. This setup allowed the wearer to see the discs indicating the next and previous hours rotate both into and out of position.

Although Breguet and a few others used variations of the wandering hours display sparingly since its inception centuries ago, the Audemars Piguet Star Wheel set a precedent for its use in the modern era. Since the Star Wheel debuted, brands such as Hautlence, H. Moser, Arnold & Son, and most notably Urwerk have all adapted this display to varying degrees in their watches.

Renaud & Papi

In 1992, Audemars Piguet invested further in the future of high horology. That year, it became the majority shareholder of complications specialist Renaud & Papi. The workshop was founded in 1986 by former Audemars Piguet watchmakers Dominique Renaud and Giulio Papi. The two had left AP when they were told it could take them decades to start working on high complications. Since then, through projects with other brands, including the development of a minute repeater for IWC’s Grande Complication, the duo had gained a reputation for their amazing work.

The duo had even worked with Audemars Piguet as a client, so when they approached the brand seeking an investor, then-CEO Georges-Henri Meylan felt it was right to incorporate their expertise back into the company. On the condition that Renaud & Papi could still take on outside clients, Audemars Piguet purchased 52% of the company. It became Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi (APRP), and it has since served as a breeding ground of talent in high horology. Industry greats such as Stephen Forsey and the Grönefeld brothers would even get their start there. Today, APRP is Audemars Piguet’s go-to source for highly conceptual proprietary movements.

The next generation of an icon

In 1993, Audemars Piguet released the Royal Oak Offshore. Nicknamed “the Beast” at 42mm wide and 15mm thick, its dimensions were unthinkable in 1993. The rough-and-tumble younger brother of the Royal Oak was designed by Emmanuel Gueit. The final design was the result of a four-year journey marked by doubt and criticism from within AP itself. Tasked, however, with creating a more masculine Royal Oak even better-suited for sport, Gueit maintained a strong conviction in his jarring design. You can read all about the ROO “The Beast” in this 25th-anniversary overview we did in 2018.

The Offshore featured not only a bulkier case and bracelet but also a visible rubber gasket between the bezel and the case, as well as a rubber-coated crown and pushers. The watch utilized the JLC 889-based caliber 2126/2840 with Dubois Dépraz chronograph module. To reduce the visual impact of the thick module on the date display, a magnifier actually sat within the dial itself. Like the original Royal Oak, which had similarly garnered plenty of initial criticism, the Offshore went on to become a best-seller for Audemars Piguet, and has become a canvas for countless limited editions and collaborations with athletes and celebrities.

Still much more than just the Royal Oak

In 1995, Audemars Piguet debuted the Millenary as an early celebration of the new millennium. Another brainchild of Guiet, the Millenary featured a unique 39x35mm oblong oval case. Earlier models in steel featured relatively simple black military-style dials, large luminescent Arabic numerals, and luminescent sword hands. The line expanded to include precious metals and complications, including chronographs, perpetual calendars, and even the wandering hours display. After the new millennium arrived, the styling became even more unique. Cases came in a variety of sizes up to 47mm, and asymmetric dials gave the impression of an offset display. Years later, the Millenary 4101 would receive a true offset time display and an exclusive ovular movement. This caliber, with its reversed architecture, allowed the balance wheel to be viewed from the front. Today, the 4101 is the most emblematic model within the Millenary collection.

Examples from the Jules Audemars and Edward Piguet lines. Image credit: Timeline.watch and Veryimportantlot.com

It was in the 1990s, however, that Audemars Piguet placed particular emphasis on sorting its catalog into distinct collections. While the watches within each of them featured a range of complications, each collection followed a general theme. Of course, the Royal Oak would serve as the versatile, always-appropriate icon. The Royal Oak Offshore would be the brand’s rugged sports watch. The Millenary collection would be distinguished by its oval shape, complementing the classically styled Jules Audemars and Edward Piguet collections. These last two collections utilized round and rectangular cases respectively. While there were some outliers, models from these core collections would make up the bulk of releases for the next two decades.

“Sunrise, sunset… Swiftly fly the years”

In 2000, Audemars Piguet celebrated its 125th anniversary. Several models, such as the Millenary Star Wheel, were introduced in commemoration. Two models from that year, however, were particularly historic for the brand. The first was the Jules Audemars Equation of Time. The watch combined an automatic perpetual calendar with an equation of time complication. This somewhat impractical but nevertheless impressive complication indicated the +/-15-minute difference between true solar time and Earth’s “civilian” time with a beautiful sun-tipped hand.

This watch was also the first wristwatch ever to include locally specific sunrise and sunset indicators. As a special-order exclusive, these were custom-manufactured based on the longitude and latitude of the client’s specified location. To this day, should the client relocate or the watch change ownership, Audemars Piguet has them covered. The brand will manufacture new sunrise/sunset indicator cams for any location in the world, albeit at a significant cost.

The ultimate chiming watch

The second groundbreaking model released in 2000 was the Jules Audemars Dynamographe. The watch featured the manually wound caliber 2891 with petite sonnerie for chiming hours on passing, a grande sonnerie for chiming hours and quarters on passing, and a minute repeater function for chiming hours, quarters, and minutes on command. The watch used a “carillon” mechanism with three hammers and gongs to chime three different pitches, rather than the standard two found on most minute repeaters. The sonnerie functions could also be switched on or off at will. On the dial were both a power reserve indicator for the repeater’s mainspring and the watch’s namesake dynamograph complication.

This world-first, developed by in-house specialists Renaud & Papi, used a direct force sensor to let the wearer know how much torque the mainspring was producing at any given moment. By winding the crown, the wearer could adjust the torque either up or down to an optimal middle ground, thereby increasing the accuracy of timekeeping. Manufactures like Jaeger-Lecoultre and Richard Mille would also go on to produce their own takes on this complication.

The Royal Oak gets a futuristic facelift

2002 was the 30th anniversary of the Royal Oak, and Audemars Piguet marked it with the daring release of the Royal Oak Concept Watch 1. This next-generation re-imagining of the Royal Oak featured a behemoth of a case. It measured 44mm wide, 18mm thick, and 57mm lug-to-lug. Constructed from a cobalt/chromium/tungsten alloy called “alacrite 602,” it was twice as hard as stainless steel. Atop it lay a grade 5 titanium bezel that curved with the contour of the case itself. Inside the watch, however, was where the real goodies lie. The Renaud & Papi-engineered caliber 2896, unhindered by a dial, was on full display. It featured a dynamographe, a linear power reserve indicator, an indicator for the crown’s time-setting/neutral/winding modes, and a tourbillon. The unique snake-like tourbillon bridge made it extremely resistant to shock.

Many watch collectors who were active at that time recall the Concept Watch 1 as the release that defined high horology for the new millennium. It forged an avenue for not just the tried and traditional, but also the audacious and avant-garde. The model even spawned a collection of its own. True to its “Concept” name, it serves as a platform to test Audemars Piguet’s latest and greatest complications and construction.

Always pushing the boundaries

2007 saw the release of the Royal Oak Carbon Concept. This was the first watch to feature a case made entirely from light and durable forged carbon. In 2015, AP released the Royal Oak Concept Laptimer. Requested by racer Michael Schumacher, it allowed the mechanical timing of laps using the APRP triple-column-wheel 2923 caliber. The movement featured dual central chronograph seconds hands with alternating flyback capabilities. This capability truly distinguished the watch from a standard split-second chronograph. In 2016, the Concept Supersonnerie set a new standard for minute repeater sound quality using a variety of innovations absolutely undeserving of summary and detailed brilliantly here. The watch also featured a tourbillon and 30-minute chronograph.

Many releases throughout the 2000s and 2010s further expanded on the collections by infusing them with a range of complications. In 2013, the super-sporty Royal Oak Offshore was even fitted with the super-traditional grande complication. The collections also saw a vast array of materials and finishes, with Royal Oaks in titanium, full ceramic, and frosted gold. Not all of the collections survived, however, with the rectangular Edward Piguet collection falling out of favor first, later followed by the Jules Audemars collection. While the Millenary collection remained in the catalog, it also remained overshadowed by its more iconic Royal Oak stablemates. Audemars Piguet, a victim of its own icon’s success, gradually became known for the Royal Oak, its variants, and nothing more in the modern era. In 2019, however, the brand took a stab at changing this perception by launching an entirely new collection, the Code 11.59.

The first new collection in years

In a potential throwback to the Jules Audemars collection, the Code 11.59 utilized a round case with a highly polished bezel. This case appeared very simple from the front. Indeed, almost too simple. Upon rotation, however, the case revealed a brushed octagonal middle and skeletonized lugs with hexagonal screws. Simple stick hands made their way around a large, open dial. Applied numerals and a date window at four-thirty complemented the baton hour markers. The dial displayed a beautiful sunburst finish in a variety of vibrant colors, with a double-curved sapphire crystal shielding it.

The Code 11.59 seemed to fuse elements of the Royal Oak with those of more classically styled pieces from the brand’s back-catalog. Like its more iconic brethren before it, was met with criticism immediately following its release. While people had criticized the Royal Oak and Royal Oak Offshore for their “overwhelming” design, they now criticized the Code 11.59 for an “underwhelming” one. Nevertheless, the brand forged ahead, doubling down in true Audemars Piguet fashion. The brand continues to expand the collection, equipping it with its signature complications. The Code 11.49 collection now includes perpetual calendar chronograph, tourbillon, and even grande sonnerie calibers.

Throwback to the ’40s

In 2020, Audemars Piguet reached back into its 1940s catalog for inspiration and pulled out the 500-piece limited edition [Re]Master01. Aesthetically based on the reference 1533 from 1943, the automatic chronograph’s mostly stainless steel case features a rose gold bezel, crown, and pushers. A yellow gold dial, rose gold time-telling hands, and thermally blued chronograph hands give the watch a truly vintage aesthetic. The AP 4409 caliber inside, however, is modern in every way. It beats at 28,800 vibrations per hour, has a 70-hour power reserve, and includes a flyback chronograph complication. At the time of writing, this model is the only one in the series. With Audemars Piguet’s catalog listing the [Re]Master as its own collection, however, it will be interesting to see how the brand expands this line.

Onward and upward

And so, as we reach the end of our journey through the history of Audemars Piguet, I ask you, dear Fratelli, to take a moment to recall all of the historic achievements the brand has fought hard for in its 146 years. From its execution of the most challenging complications to the development of completely new ones, from the pioneering use of experimental materials to an impressive list of world firsts, the brand’s history is far too rich to write it off as a single model success story. The question now is, just what will the 2020s hold in store for the manufacture from Le Brassus?

With its milestone 150th anniversary on the horizon in 2025, will we see a thrilling new horological masterpiece, years in the making? Will the Code 11.59 catch on, serving as the brand’s icon for the next generation of watch enthusiasts yet to be born? Or will Audemars Piguet find the most success in returning to its roots in classical design thanks to modern manufacturing? It’s hard to say, but whatever happens, you can be sure to hear about it here on Fratello. Thanks again for coming with us on this journey through time, and let us know what your favorite Audemars Piguet watch is in the comments below!