A Brief History Of Time: Bvlgari’s Watchmaking History — Part One: 1884–2010

OK, be honest with me. When you hear the name “Bvlgari”, what are the first things that come to mind? Gold? Diamonds? Snakes? A “funny name” spelled with a V instead of a U that’s pronounced like a U anyway? Or, dare I suggest, high horology? If you’re reading Fratello, it’s probably safe to assume you’re at least somewhat familiar with Bvlgari watches. However, I’d be willing to bet every last penny of my lunch money that “high horology” was not the right answer to that question.

I’ll be honest with you. As a child of the ’90s, for the longest time, I merely associated Bvlgari with Colosseum-shaped rings and boldly branded bling. And therein lies a dilemma. How does a legendary jewelry brand cross over into the horological landscape, wriggling its way into the hearts of watch lovers worldwide? It’s a formidable task that several in the luxury world have undertaken, but few have accomplished. And yet, Bvlgari has been making remarkable headway in horology in recent years. In 2021, for the first time in my watch-collecting career, I see Bvlgari watches making the grail lists of industry pros and casual enthusiasts alike. So how did Bvlgari do it? What, exactly, led up to the brand’s immense crossover success? That, dear Fratelli, is what we’re here today to find out. Join us, as we discover the watchmaking history of the Italian powerhouse, Bvlgari.

Born of silver

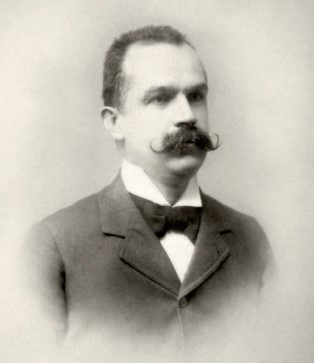

Bvlgari was founded by Sotirios Voulgaris, a creative and ambitious craftsman from the renowned silversmithing region of Epirus, Greece. Born in 1857 and the only survivor among his parents’ 11 children, Voulgaris spent his childhood in the family’s shop in the town of Paramythia. There, he learned the silversmithing arts under the tutelage of his father, who made belt buckles, sword sheaths, and silver jewelry. In 1873, however, oppressive Ottoman rulers set fire to Paramythia, destroying the entire town and the family’s shop in its wake. Voulgaris and his father fled their home, spending four years on the road between Greece and Albania, and selling their silver creations wherever they could. In 1877, the family finally settled on the tranquil Greek island of Corfu. There, they opened a new shop, where the 20-year old Sotirios met Macedonian goldsmith, Demetrios Kremos.

Kremos became Voulgaris’s mentor, and in 1880, the pair felt Italy calling their names. The two men left Corfu and settled in Naples, where they opened a small shop selling their crafts. Though the shop was successful, its success made it a target for theft. In 1881, thieves robbed Voulgaris and Kremos of everything, and the pair decided to leave Naples for Rome. Though he arrived in Rome with only 80 cents to his name, Voulgaris’s dream of prosperity motivated him.

In Rome, the pair struggled initially. However, thanks to a Greek storekeeper who allowed them to display their wares in his sponge shop window, Voulgaris and Kremos were able to sustain themselves. Over the next three years, the pair were able to save enough money to open their own shop.

The first shops in Rome

Voulgaris and Kremos opened their first shop in Rome in 1884 at 75 Via Sistina. After a few months, however, they decided to part ways. More motivated than ever, Voulgaris went into business for himself. Romanized his name to “Sotirio Bulgari”, he opened his own shop selling his silver creations at 85 Via Sistina, and worked relentlessly to grow his business. He even set up a seasonal point-of-sale in ritzy St. Moritz, Switzerland. In 1894, he opened a second location in Rome at 28 Via dei Condotti. People on their way to the St. Peters Basilica passed the shop, and the silver jewelry, artisanal silverware, antiques, and “curiosities” in the window attracted plenty of wealthy patrons. Over the following ten years, Bulgari’s business boomed. He hired Greek artisans and even his own relatives to help with his expansion.

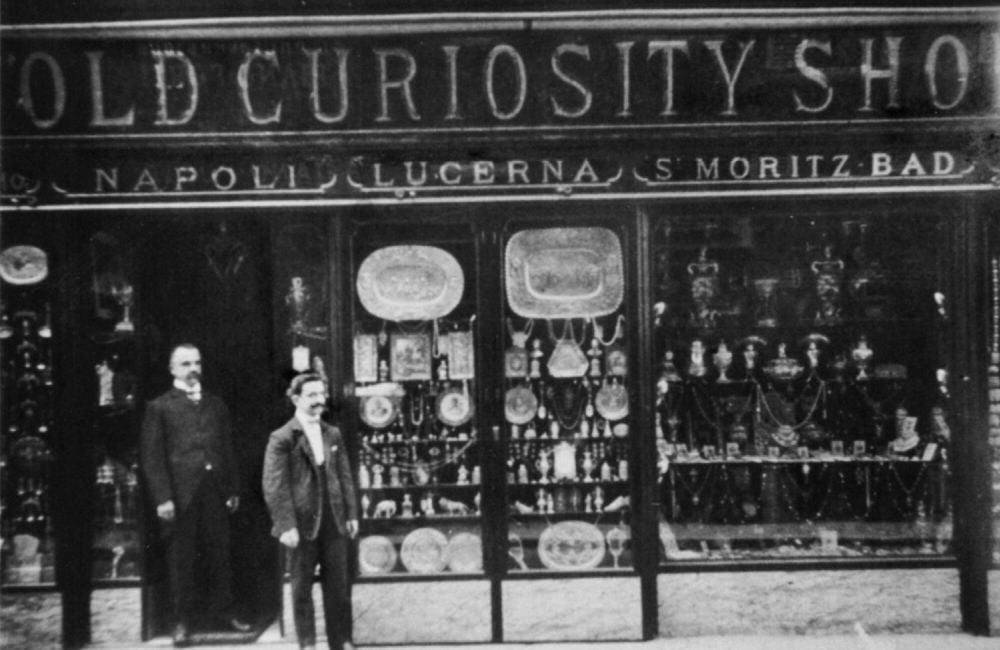

As the Bulgari name garnered more and more acclaim, he expanded further. In 1905, he opened another larger shop in Rome at 10 Via dei Condotti, originally naming it the Old Curiosity Shop to attract wealthy tourists. This location remains the brand’s flagship store to this day. By 1908, there were seven permanent Bulgari shops and two seasonal points of sale between Italy and Switzerland.

In the 1910s, Bulgari’s sons Giorgio and Costantino joined him in the business. Around this time, Bulgari’s focus turned completely to jewelry. As Giorgio and Constantino Bulgari took over their father’s role, the brand produced lavish jewelry inspired by Parisian trends. Sotirio Bulgari passed away in 1932 at the age of 75. In 1934, his sons renovated the brand’s flagship location and adopted the BVLGARI trademark written in the classical Roman alphabet. Under the sons’ leadership, Bvlgari would become an international phenomenon.

Bvlgari’s first watches

In the 1920s, the brand made jewelry watches for ladies. These “wristlets” very much echoed the Art Deco styling cues of Bvlgari’s jewelry in that era. Many featured platinum cases and bracelets, completely set with diamonds. As wristwatches began to catch on, Bvlgari even produced some timepieces for men.

The watch seen here is the only example of a men’s piece from this era that I have seen. Set in a platinum case, the dial uses a Greek key motif, paying tribute to Bvlgari’s Greek heritage. At the heart of the watch lies a jump hour movement. Since Audemars Piguet produced the first jump hour wristwatch in 1921, the jump hour complication had surged in popularity. Though the supplier of the movement in this watch is unclear, Bvlgari often used movements from esteemed Swiss makers like Jaeger-LeCoultre, Vacheron Constantin, and Audemars Piguet. Interestingly, the watch also has an error on the dial, with the numerals for “30” where “35” should be.

As was widely accepted in the jewelry industry at the time, Bvlgari also sold double-branded timepieces. In the example seen here, circa 1941, an Audemars Piguet movement is set within a French 100 Franc coin from 1863. The double-branding strategy was likely mutually beneficial, lending more repute to both Bvlgari and its collaborators in their complementary industries. Bvlgari would continue this practice for several decades.

The first iconic Bvlgari watch

In the 1940s, Bvlgari introduced a watch that would become an icon of style — the Serpenti. The unique design drew on ancient Greek and Roman tradition, in which snakes were symbols of vitality, good fortune, fertility, and protection. As snakes had been a motif in Mediterranean jewelry for millennia, Bvlgari drew on both its Greek roots and Roman surroundings to create an unmistakable design. A flexible Tubogas (“gas pipe”) bracelet coiled around the wearer’s wrist. Decorated with intricately textured snake scales and a diamond-set serpent head and tail, the Serpenti was both edgy and elegant. The snake’s mouth opened and closed on a hinge, which the wearer could flip to reveal the dial.

Over the following decades, the Serpenti design would evolve as Bvlgari utilized new materials and design elements. The use of enamel became a colorful and popular theme. Bvlgari used colorful gemstones like sapphires, emeralds, and rubies for the serpent’s eyes. The brand continued to use high-quality mechanical movements from Movado, Jaeger-LeCoultre, and others to power the watches. While some dials were double-branded, many were often signed with only the movement maker’s name.

Double-branded Vacheron Constantin and Bulgari Tubogas watch, circa 1960s. Image credit: Thekeystone.com

In the 1960s and ’70s, Bvlgari complemented the ornate offerings in the Serpenti line with simpler variations. These featured visible dials in a variety of case shapes. The bracelets of these models highlighted the Tubogas manufacturing technique, in which two strips of gold are first wrapped around a core. The edges of the strips interlock, resulting in a design almost completely free from soldering. The core is then removed, leaving the resulting product incredibly flexible.

A turning point for Bvlgari watches

Bvlgari’s Serpenti watches surged in popularity thanks to movie stars like Elizabeth Taylor. By the 1970s, the brand had really settled into its own design language, which now drew heavily on Roman architecture and heritage. The turning point for Bvlgari’s watches would come in 1975 when the brand produced the Bvlgari Roma. Its design linked past and present, with a flat, yellow gold case inspired by ancient Roman coins and the digital display so en vogue at the time. The strap was a combination of leather and hemp macrame with a yellow gold buckle. Bvlgari only produced 100 pieces of this watch as a gift to its most loyal clients. Nevertheless, the design drew massive amounts of critical acclaim, and Bvlgari brought an analog version to market that same year.

In 1977, according to the vision of third-generation CEO Gianni Bulgari, the brand released its first larger men’s watch, the Bvlgari Bvlgari. Very similar in design to the Roma, the bezel featured deeply engraved Bvlgari branding, once again inspired by ancient Roman coins. The first models were 33mm, and as popularity surged, 30mm, 26mm, and 23mm variants were also added to the collection. The design of the bezel and the 12 and 6 numerals would influence the design of nearly all of Bvlgari’s watches for decades thereafter. Like the Serpenti, the Bvlgari Bvlgari remains in the brand’s collection to this very day. It has seen variations in steel, platinum, and rose gold, with both metal bracelets and leather straps, with and without date windows, and even a chronograph complication.

In 1984, Bvlgari opened a branch in Switzerland called Bvlgari Time to oversee the production of its watches. All Bvlgari watches would go on to bear the Swiss Made label.

The first Bvlgari sports watches

In 1988, Bvlgari introduced the Diagono. It was the brand’s first foray into the realm of sports watches. The name reportedly came from both the diagonal slope of the bezel and the Greek word agón, meaning “contest.” Produced in steel with a quartz chronograph movement, the design was notable for its use of the Bvlgari logo on the bezel and its integrated strap/bracelet design. The original chronograph models were available in 35mm cases. Not long after, 38mm three-hand variants would follow.

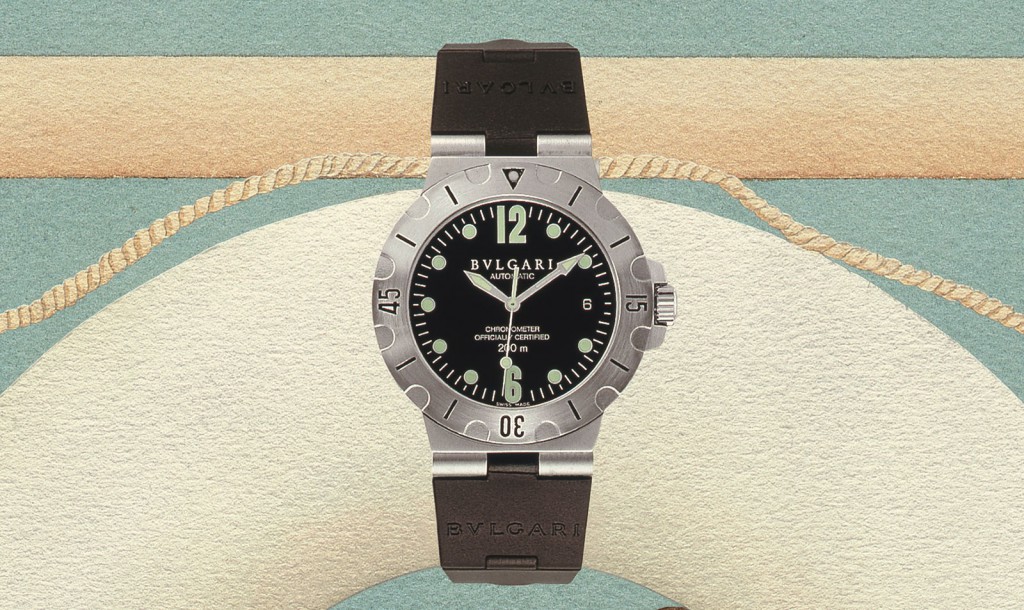

In 1994, the Bvlgari released its first dive watch, the Diagono Scuba. Even sportier than the previous Diagono, the Scuba featured an automatic, COSC-certified movement, luminescent hands and indices, 200m of water resistance, and a unidirectional bezel. The Diagono Scuba came on a unique rubber strap, with two hinged trapezoidal links on either end echoing the stainless steel bracelet of the previous Diagono.

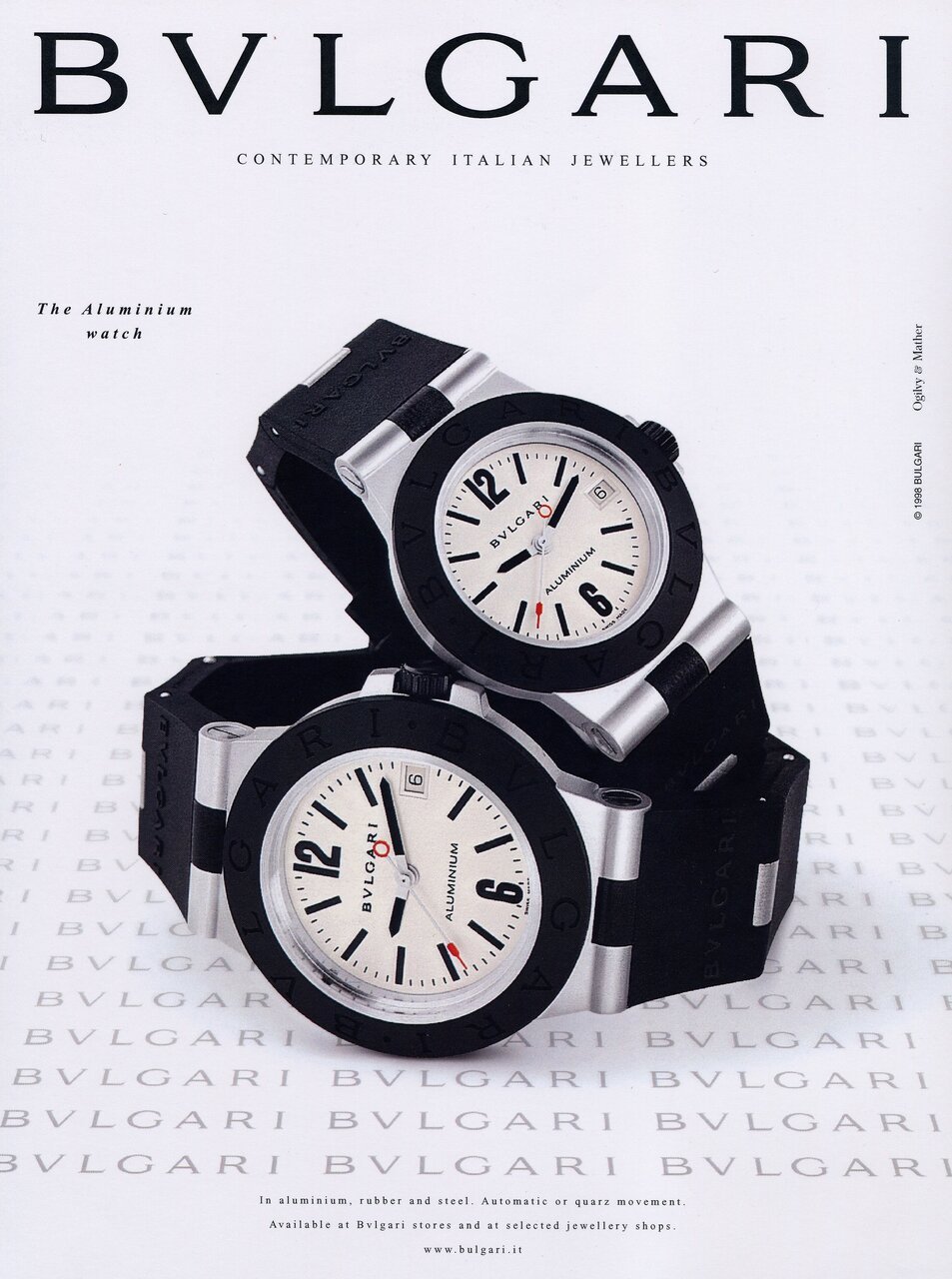

Then, in 1998, Bvlgari released another future brand icon, the Aluminium. An evolution of the original Diagono, the Aluminium featured an aluminum case, rubber bezel, and rubber strap with rubberized aluminum links. The watch came in small, medium, and large sizes for men and women. The Aluminium was available in both three-hand and chronograph models, powered by quartz movements. The daring combination of materials rocked the high-end fashion world. Though no one may have guessed at the time, it also foreshadowed the future of Bvlgari sports watch design, as the brand would later embrace several alternative materials.

Gérald Genta Bi-Retro and Daniel Roth Double Dial Regulateur Tourbillon. Image credit: Christies.com

Pursuing high horology in the new millennium

With its stylistic icons having developed a huge following, Bvlgari turned its focus to the pursuit of true watchmaking excellence. In 2000, Bvlgari acquired both the Gérald Genta and Daniel Roth brands from The Hour Glass, one of the leading watch retailers in Asia. Gérald Genta, the famed designer of both the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and the Patek Philippe Nautilus, had started his own brand in 1969. Several of his designs featured an octagonal case, and in the ’80s and ’90s, he excelled in the production of jump hour/retrograde watches. Daniel Roth, the man responsible for revitalizing Breguet’s design language in the 1970s, had started his own brand in the late 1980s. His signature “double ellipse” case housed everything from simple three-hand movements to chronographs, retrogrades, repeaters, and tourbillons.

In terms of horological prowess, both Gérald Genta and Daniel Roth were at a level that Bvlgari itself had not yet reached. Thankfully, with their acquisition, Bvlgari also assumed ownership of the Genta and Roth manufacturing facilities in Le Sentier, Switzerland. Realizing the massive opportunity that lay before it, Bvlgari made a decision to invest in not just watches, but in watchmaking. Rather than immediately absorbing the brands into its own collection, Bvlgari would let Gérald Genta and Daniel Roth continue producing watches under their own labels for several years. Learning from them and developing its own watchmaking know-how, Bvlgari would choose to produce its first high horology pieces under its own name alone.

The first big development

Over the next decade or so, Bvlgari would forge a path into the realms of high horology, while simultaneously continuing to develop its high fashion designs. We see examples of this from 2004 when the brand released both the Ergon and the Bvlgari-Bvlgari Grande Complication. The Ergon featured a new, ergonomically styled case with an integrated strap, and it was produced in both white gold and steel. The watch came in both three-hand and chronograph automatic variants, with ETA movements at their core. On the other end of the spectrum, the Bvlgari-Bvlgari Grande Complication featured the brand’s signature case and its first proprietary high-horology movement. The caliber boasted a 64-hour power reserve, a variable inertia balance, and a tourbillon. The Bvlgari-Bvlgari Grande Complication was produced as a limited edition in yellow and white gold.

Bvlgari’s offerings start to heat up

In 2005, Bvlgari purchased 50% of Cadran Designs, a Swiss dial specialist, and 51% of Prestige d’Or, a manufacturer of steel and precious metal watch bracelets. Then, in 2006, the brand really brought the heat, releasing two new pieces in their brand new Assioma case with complicated new movements. The first of these releases was the Assioma Tourbillon Multi-Complication. The case featured a unique rotated tonneau shape with double Bvlgari signatures. Bold, sloping bars accentuated its lines and formed filigree-like lugs for a whole new look. Inside the watch was the brand-new caliber BVL 416. This impressive automatic movement consisted of 416 parts with a tourbillon, perpetual calendar, and 24-hour dual-time complications. Additionally, it was assembled and finished completely by hand. The Assioma Tourbillon was produced as a limited edition in white, yellow, and rose gold.

The second major release of the year was the limited edition Assioma Heures Retrogrades. It featured the same Assioma case with the BLV 261 movement. The inspiration for this caliber can be seen in Daniel Roth Premier Retrograde watches from the 1990s. These watches featured “6-to-6” retrograde hours and either a pointer date or sub-seconds sub-dial at six o’clock. While Bvlgari’s take on the design also featured retrograde hours and sub-seconds, the caliber distinguished itself with an additional AM/PM indicator. Like the movement in the Tourbillon Multi-Complication, all of the 261 movement components were assembled and finished completely by hand.

More pieces of the puzzle

In 2007, Bvlgari purchased 100% of Finger, a Swiss company specializing in the production of cases for high-horology timepieces. The brand also set to work developing its very own in-house base caliber, to eventually be used throughout its men’s watch collections. The culmination of this effort came in 2010 when Bvlgari unveiled caliber BVL 168 in the Sotirio Bulgari line. Having been introduced in 2009, the Sotirio Bulgari watches marked the brand’s 125th anniversary and paid tribute to its founder. The new case featured the familiar round coin shape, but with a more contemporary, cleaner bezel and angled screw-bar lugs. Roman numerals also replaced the typical 12 and 6 Arabic numerals found on most Bvlgari dials.

The BVL 168 caliber inside the Sotirio Bulgari was the first movement designed and manufactured completely by Bvlgari’s own design team. It featured central hours, minutes, and seconds, as well as a central pointer date. The 25-jewel movement had a 42-hour power reserve, 4Hz frequency, sturdy nickel silver construction, and a finely adjustable balance with a full balance bridge for high impact resistance. Diamond-polished bevels complemented its Côte de Géneve and perlage finishing. Interestingly, the 100% Swiss caliber featured a 3/4 bridge design, which many enthusiasts associate with German movement design.

Complete, vertical integration

2010 marked several other significant milestones for the brand. That year, it acquired the remaining stakes in its dial and bracelet manufacturers, Cadrans Designs and Prestige d’Or. This brought 100% of Bvlgari’s watch manufacturing processes under one figurative roof. Also in that year, Bvlgari CEO Francesco Trapani, a fourth-generation descendant of the Bulgari family, announced that the Gérald Genta and Daniel Roth brands would finally merge with the Bvlgari collection. The watches would feature both the Bvlgari and respective Daniel Roth and Gérald Genta logos on the dials. Additionally, the brands’ aesthetic cues, such as octagonal and elliptical cases and unconventional displays would live on in the Bvlgari lineup. This announcement raised many eyebrows in the watch community. However, it was a critical step in solidifying the brand’s reputation in watchmaking.

Complications galore

Bvlgari marked the occasion with 19 total double-branded releases. These pieces brought a vast array of complications into the Bvlgari collection, including chronographs, moonphases, jumping hours, retrogrades, tourbillons, and minute repeaters. A standout from the Daniel Roth offerings was the Tourbillon Rattrapante. It featured the classic double-ellipse Roth case design in a 46mm size well-suited to the times. In addition to an offset time display, the proprietary caliber DR 8300 provided a single 30-minute chronograph register, power reserve indicator, and 60-second tourbillon.

The Bvlgari Gerald Genta Grande Sonnerie Magsonic was the brand’s top-of-the-line offering. Powered by the incredible GG 31001 caliber, it featured a total of 923 components, and it was entirely handcrafted. The watch featured three chiming complications — a petite sonnerie (which automatically chimed hours on passing and quarters on passing), a grande sonnerie (which automatically chimed hours on passing, repeating them with quarters at every quarter-hour), and a minute repeater (which chimed hours, quarters, and minutes on command). With four striking hammers and four gongs, the watch rang out with the melody of the famous Westminster chimes. Employing two mainsprings for the main power reserve and chiming functions, the Magsonic was equipped with dual power reserve indicators on its reverse side. And if all that wasn’t enough, it was also a tourbillon, with a retail price of around $1,000,000 USD.

The golden design: a taste of things to come

As amazing as the Magsonic was, however, no single watch line would end up doing more for the Bvlgari brand in the coming years than the Octo. Its case, having been designed by Genta in the 2000s, was a legend in the making. The Bi-Retro, in steel and ceramic with a jumping hour display, retrograde minutes, and retrograde date, was a blend of modern aesthetics and classic Genta complications. The Quadri-Retro in rose gold added even more complexity to it, with a chronograph featuring retrograde 30-minute and 12-hour counters. An Octo Tourbillon and Minute Repeater (not pictured) brought true high horology complications to the line. Finally, the Octo Grande Sonnerie in white gold combined retrograde hours and a scrolling minute display with the most complex chiming functions the brand could offer. Equipped with proprietary and in-house movements, the watches were serious horology in every sense.

Whether Bvlgari’s management knew it in 2010 or not, the Octo design would serve as the bedrock for the brand’s watchmaking identity 10 years later. The Octo would become the foundation for the brand’s most incredible innovations in both movements and external construction. It would set world record after world record, propelling Bvlgari to the top levels of the watch industry. And perhaps most importantly, it would be the ace in the hole that would finally make casual watch enthusiasts stop and take notice of Bvlgari watches.

The story doesn’t end here

Tune back here in two weeks, as we explore the final decade in Bvlgari’s watchmaking history. If this article managed to intrigue you, you’ll definitely not want to miss Part Two. Trust me, my friends — the best of Bvlgari awaits us! Let us know what you think of Bvlgari watches in the comments below. Until next time!