“A Great Deal Of Rough Treatment” — When The Rolex Explorer 1016 Went Caving

This is a story of pioneering adventurers. It is a tale about a group of expert cave divers that may never have surfaced if not for the tireless efforts of volunteers at the Oxford University Cave Club. It was also an opportunity for the watch brand Rolex to test out its Explorer 1016 on the expedition. This is the adventure tale behind a tiny Rolex Explorer ad clipping from the 1960s.

The Rolex Explorer is one of the most iconic sports watches The Crown has ever made. After debuting in 1960, the sturdy 1016 Explorer was a mainstay for the brand until 1989. Besides a few technical updates, including an updated movement and solid bracelet design, the basic recipe remained the same. In 1971, Rolex introduced the Explorer II as an additional model in its sports line. That watch, reference 1655, was specifically for cavers, also known as spelunkers.

A caving adventure for the Rolex Explorer 1016

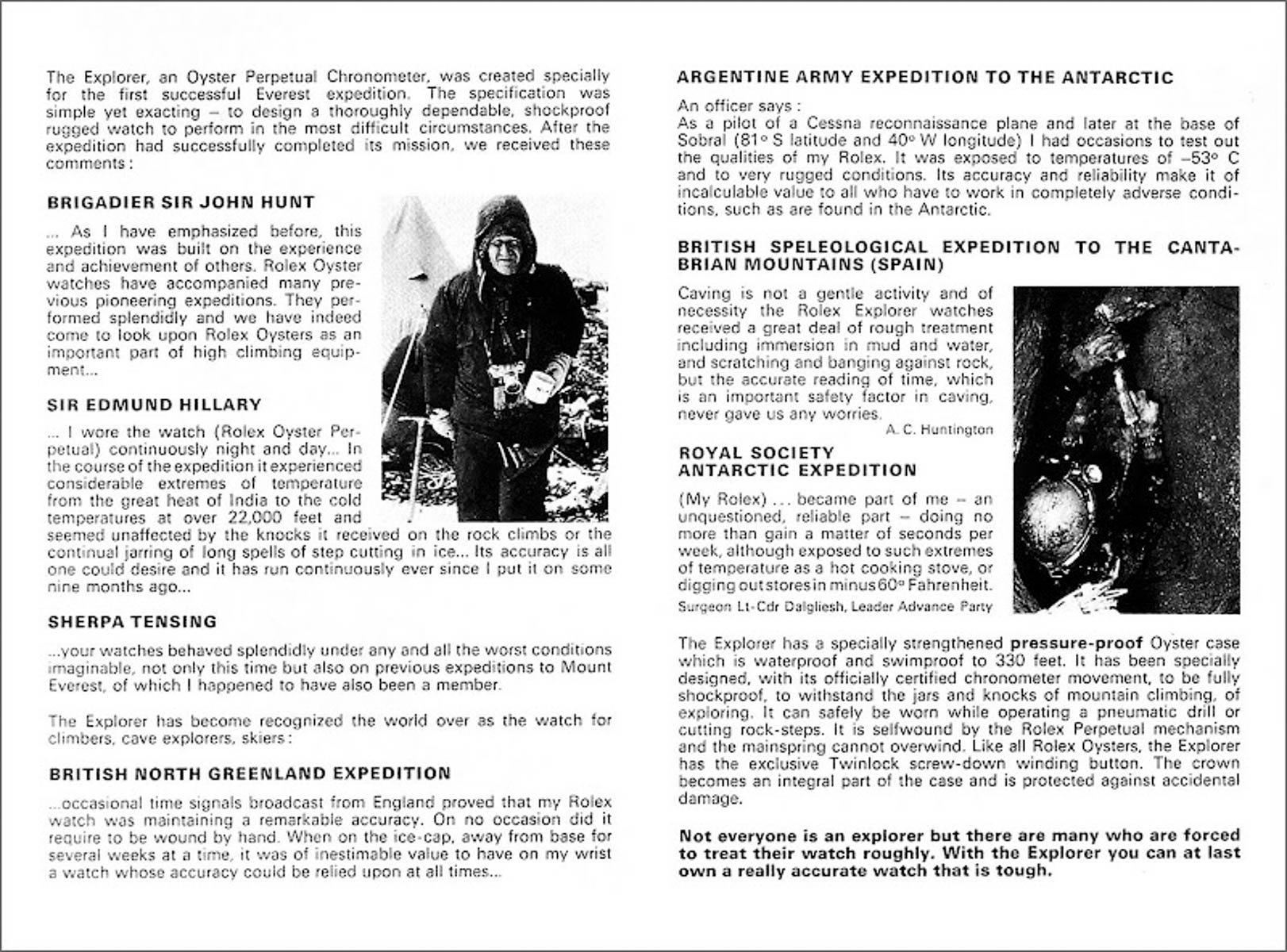

Perhaps Rolex found inspiration for the Explorer II in the success of its Explorer 1016 when British cavers used it in the 1960s. You see, some advertisements of the Rolex Explorer 1016 in the mid-to-late 1960s featured a tiny clip dedicated to an obscure caving expedition.

Today’s story, therefore, is about the Explorer ref. 1016 and how it went on its very own caving adventure in 1965. It is the story behind that tiny ad, which may have disappeared into history if not for the dedicated efforts of volunteer archivists at the Oxford University Cavers Club. We extend our thanks to them for archiving images of their expeditions for the public record. Read on.

It all begins in the Cantabrian Mountains

“The Cantabrian-Asturic Mountains cover an area of approximately 200 miles by 60 miles and run along the northern coast of Spain west of Bilbao,” starts the diary entry of what would become the official account of the British Speleological Expedition to the Cantabrian Mountains of Northern Spain. “This is [our] hunting ground,” it continues.

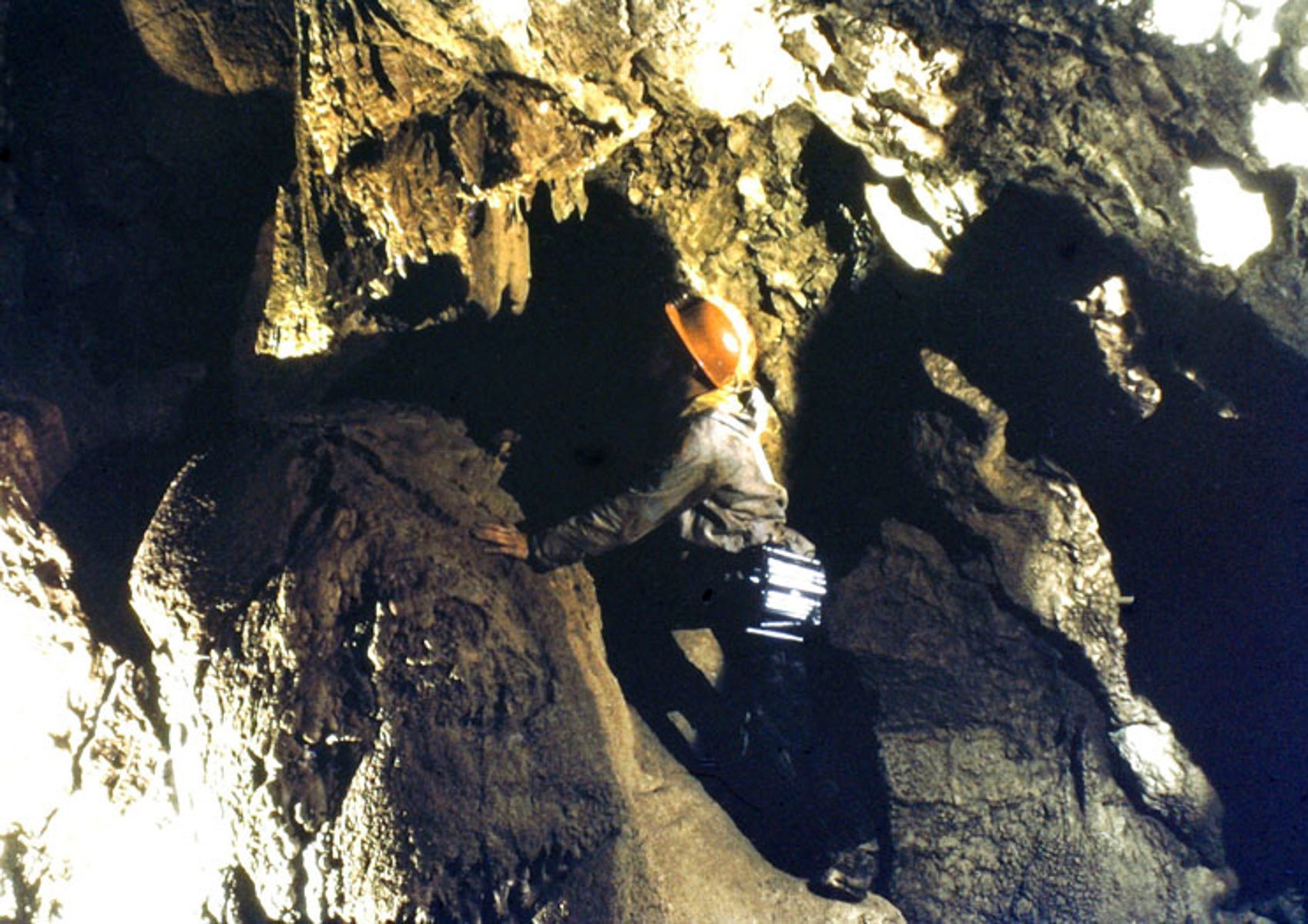

The forbidding peaks of the Cantabrian Mountains can rise to more than 8,000 feet, the writer notes. But this is no expedition for mountaineering. Rather, it is the inverse — cave exploration, also known as spelunking, the elite sport of mapping, marking, and admiring the world’s known and unknown depths. The central group of the Cantabrian Mountains goes by the name Picos de Europa. This place, with a rabbit warren of unexplored cave sites, is the setting of this tale.

An ambitious Anglo-Spanish expedition

In 1965, a group of British and Spanish spelunkers, many of whom were university students, embarked on the most ambitious expedition to the Cantabrian Mountains to date. In 1961, 1962, and 1963, expeditions by Oxford University uncovered hints of what could be a vast cave network with the prospect of large caverns, one of the underworld’s true wonders. The British cavers had heard from Spanish counterparts from León that several large underground systems were still out there, beckoning exploration.

While they knew the approximate location of these systems, no one could tell how large or lengthy they might be. An expedition started to gather momentum, but it would need extensive planning and preparation. Around 30 cavers from 16 clubs across the UK would team up with a further 15 Spanish cavers from León. With the possibility of many deep caves, it would be necessary to provision for manning an underground camp. The expedition would last for as long as university breaks would allow — between July 26th and August 20th.

Rolex watches for a tough journey

In going through the official account of this expedition, it is clear that it involved a significant logistical effort. Many leading brands received acknowledgment for their help in providing supplies. These were everything from tough Levi’s jeans to Bovril (presumably, jars of the vegemite/marmite-like substance for the trip). One of the companies in those acknowledgments was Rolex. This is because the brand provided the still relatively young Explorer ref. 1016 to the British members of the expedition.

In the official advertisement for the Rolex Explorer, Antony C. Huntington, chairman of the Oxford University Cave Club and a lead member of the expedition, noted how these watches survived significant abuse in the unfolding adventure. “Caving is not a gentle activity and of necessity the Rolex Explorer watches received a great deal of rough treatment, including immersion in mud and water, and scratching and banging against rock, but the accurate reading of time, which is an important safety factor in caving, never gave us any worries,” he explained.

Not a walk in the park

It was an ambitious trip, even for the dedicated cavers. The Oxford University Cave Club, which was taking a leading role in the expedition, had previously gone caving in nearby Wales, Somerset, and Derbyshire, but this remote part of Spain was different. Smaller expeditions had been attempted but nothing on this scale.

“The first few days were spent acclimatising to the extremely high daytime temperatures and arranging methods of exploration with the Spaniards. This had to be done in two ways: firstly, caves reported by the Spaniards had to be thoroughly investigated by us, and secondly, the surface had to be searched methodically in the hope of finding new systems. The first provided many disappointments as most of the caves did not realise their full potential,” the expedition’s account reads. Besides the sheer 8,000-foot peaks, which meant a reasonable risk of rock slides, weather conditions could be treacherous. The British found it hard going in the heat during the day and the cold at night.

The exploration begins

The cavers set up camp at the Spanish village of Valporquero, near the entrance to a large known cave site. From there, they would explore the surrounding terrain, pockmarked by caves and cliffs, for two weeks before reassessing their location.

“Two weeks had passed, and by splitting up our members into small groups, the caves and the area between the rivers Bernesga and Porma had been fairly thoroughly searched. The expedition’s potential had not been fully realised, and the chance of finding any other large caves in the area seemed remote,” the official account of the expedition reads.

“To the cast of the area we knew of a large shaft ‘Jou Cabau’ which had only been partly explored. In 1963 it had been located by a small reconnaissance party with neither the equipment nor time to make the full descent. In moving to Cangas de Onis we could thoroughly investigate this shaft and, by remaining semi-mobile and working from a central campsite, explore the locality.”

Into the cave’s maw

After these two weeks, the British team discovered some of the largest and previously unexplored cave sites in Northern Spain. The expedition moved to the site near the town of Cangas de Onís, north of the Picos de Europa. Most of the caves found there were completely new, the account says. However, there was one, reported on a previous expedition, that required investigation. Called Jou Cabau, it was reportedly a large-diameter shaft high in the mountains to the east of Cangas de Onís.

“This was found on inspection to consist of a cylindrical shaft, about 150’ in diameter, between 175’ and 200’ deep, filled with 15’ of snow at the bottom. The perimeter of the cylinder on one side was riddled with smaller shafts, which were connected at their bases to the bottom of the main shaft. As these were on the uphill side, they probably took most of the surface water in times of heavy rainfall,” the expedition’s account states.

Tough conditions, even for experienced cavers

It would be hard going with much water and snow in parts of the cave systems. This undoubtedly would have put the cavers and their Rolex Explorer 1016 watches to the test. “On the opposite side of the cylinder, a small, well-decorated passage led to a thin, but very tall, rift. This was descended in stages, using 175 feet of ladder, to a narrow stream passage at right angles to the rift. Upstream probably led back to the bottom of the main shaft, but the way was stopped by a difficult climb. Narrowing of the passage stopped any progress downstream. The total depth of the pot was estimated at 500 feet.”

The team would explore many different cave entrances in the last days of the expedition before returning home in August. In doing so, they had to battle strong winds capable of extinguishing carbide lamps and large variations in temperatures, making conditions quite uncomfortable at times. At some stages, the gaps to the roof were so small that the team would have to engage in uncomfortable, muddy crawls. Some of the passageways were quite tight, and some entrances were as small as five feet.

The expedition comes to an end

Having explored dozens of cave systems over several weeks, the cavers were getting increasingly tired in their efforts. Much had been explored, but much had yet to be mapped and surveyed. However, according to their account, they had achieved the first and main aim of the 1965 British Speleological Expedition to the Cantabrian Mountains — “to explore and survey the caves in the mountains to the west and south of the Picos de Europa, and do this in collaboration with the local speleologists and geologists from León.”

At an early stage, the cavers had hopes of finding caverns of great length and depth, perhaps even record-breaking sizes. “But our hopes for depth did not materialise. We did, however, find many interesting and quite large systems during our extensive search of a hitherto unknown caving area,” their account states.

Closing thoughts

Thankfully, this would provide momentum for the club to continue adventures in Spain in the following decades. “We feel, in fact we know, that there are many more caves yet to be found in this part of Spain. Some may even be open to the surface, but many more will not be entered unless some digging is undertaken,” the account reads. And the Rolex Explorer 1016 was an invaluable part of that early foundational expedition.

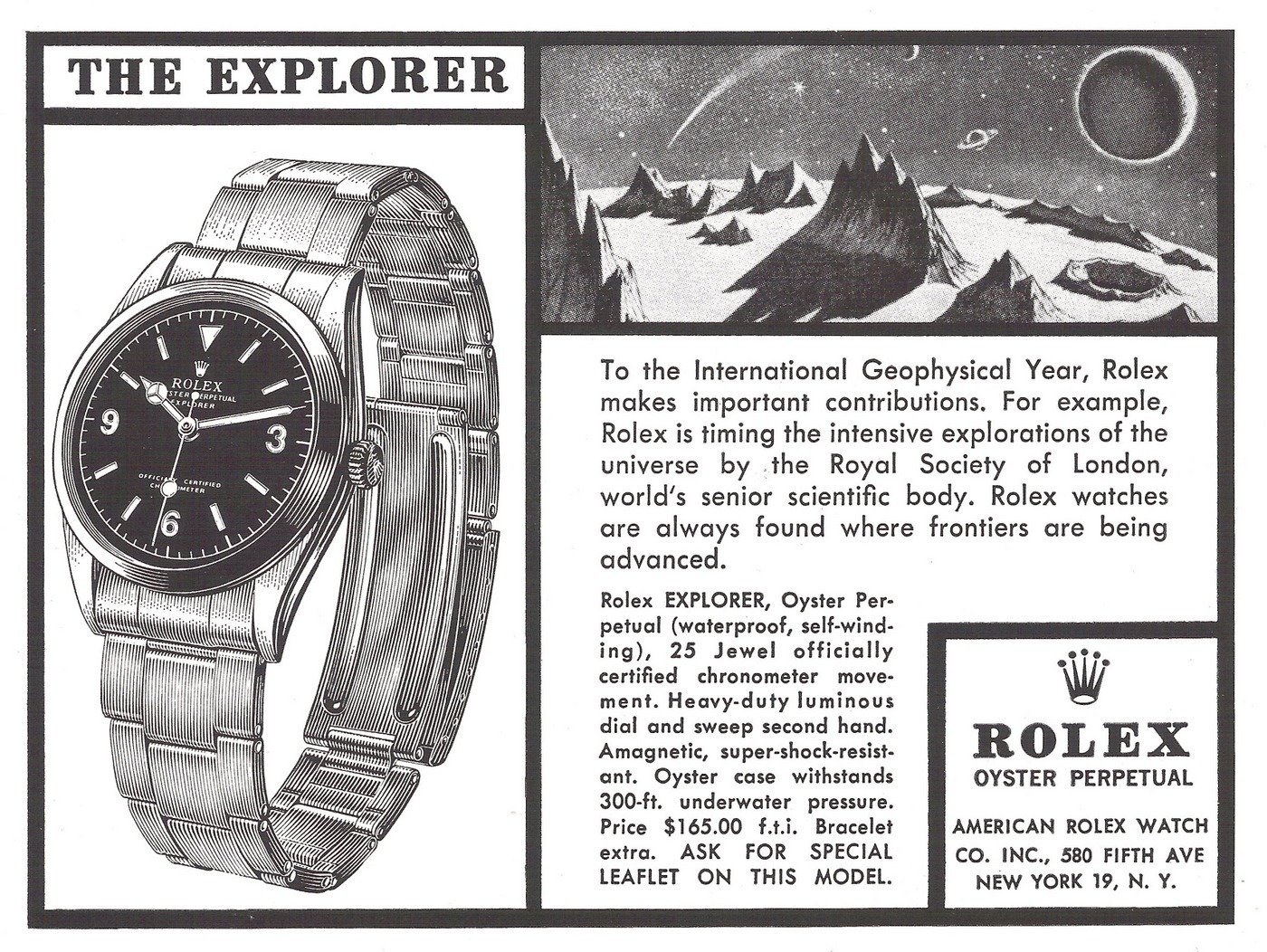

I would love to read your thoughts on this early adventure, Fratelli. How do these marketing campaigns compare to the modern ones by Rolex? I feel these stories of adventure and battling extremes recall Rolex’s heritage as the premier maker of fine tool watches. Let me know what you think in the comments. In the spirit of earlier adventurers, I leave you with an old Rolex ad from the International Geophysical Year (1957–1958).