An IWC Manufacture Visit 80 Years In The Making

It is a spring morning (April 1st, 1944, to be precise), and members of a US Air Force bombing squadron have set their sights on what they believe is their target — the German town of Ludwigshafen am Rhein near Mannheim. Unknown disaster looms for the Swiss town of Schaffhausen…

The group of 15 from a larger squadron of 50 or so B-24 Liberators, each plane with its four massive supercharged 14-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-1830-35 Twin Wasp engines, could be heard long before the planes were seen in the sky. At 10:58 AM, the combined payload of the heavy bombers, amounting to 371 incendiary and high explosive bombs, is dropped. Sixty tons of munitions hurtle down on the unsuspecting town of Schaffhausen near the Swiss-German border. The bombers have mistakenly released their deadly payload on the wrong country.

How did they get so lost? According to an article that refers to an interview with one of the bomber crew’s squadron commanders, new radar technology malfunctioned, and weather hampered a visual reference to make any corrections. As the formations of heavy bombers moved across France and into Germany, they ran into cloud cover as high as 21,000 feet (6,400 meters). That’s where the radar should have saved the day. Except it malfunctioned, which meant the B-24s had to guess whether they were bombing the right place without visual reference to the terrain, and the lead navigator had to rely solely upon prebriefed estimates of winds aloft to carry out his dead-reckoning type of navigation. It was practically guesswork.

A day of infamy

The bombers are a full 235 kilometers (146 miles) off target. As Schaffhausen sits on the north side of the Rhine River, the pilots assume that it is the German town of Ludwigshafen am Rhein. Crowds have gathered on the streets of Schaffhausen to see the planes in the sky, alerted to their presence by not only the sound of the engines but the town’s air raid sirens too. The air raid alarm sounded over 500 times in Schaffhausen during the war. Almost every time, nothing happened, and the population got used to it. But this would not be one of those false alarms. Because the air raid sirens have sounded so many times before without an attack, and Switzerland is a neutral power, many feel safe and don’t take cover until it’s too late.

It’s now 11:00 AM. Bombs start making impact everywhere, ripping through stone structures and turning buildings into rubble. Within minutes, dozens are killed (some estimates put it as high as 60), hundreds are homeless, and a thousand are now without work because the factories are smoldering ruins. Fire crews rush to put out the fires. At the International Watch Company (IWC) factory in Schaffhausen, a bomb smashes through the rafters but fails to detonate. The flames from incendiary ammunition exploding nearby threaten to engulf the building. Members of the watch company’s fire brigade just manage to put out the flames before they spread. The level of destruction can be clearly seen in these remarkable historical images.

This map shows where the bombs fell on the town. The damage is so severe that a secret document written later in the war reveals American concerns over the country’s future relationship with the Swiss after the accidental bombing.

A family connection

Schaffhausen — and, by extension, IWC — is wrapped up in my extended family’s history. Among those killed that day in 1944 was my great-grandfather Jules Meister. He is commemorated along with the other 39 individuals officially killed in the 1944 American bombing of Schaffhausen. According to his grandson Gerry Meister, he was standing on the steps of the post office when “he saw the bombs dropping. He ran for safety into the underground passage leading to the railway station. The post office was spared, but the station and the underground passage were destroyed.” In this map, you can see the locations where civilians were killed, including Jules Meister.

Jules’s son Fritz Meister married my grandmother Wendy in 1972. My grandfather Fritz also happened to love watches. Fritz was a sharpshooter in the Swiss Army. He joined at age 17 when there were constant concerns that Switzerland could be invaded. It was a time when many in Switzerland genuinely feared that they too could become an occupied people and join the likes of The Netherlands, France, Czechoslovakia, and many others under Nazi rule. Fritz was born in 1918 in Schaffhausen, and he had a fondness for IWC because of the connection it had with his birthplace. He enjoyed a sense of pride that a company from his hometown made such great watches. As a result, his constant companion on any and every task was an IWC Caliber 89.

My grandfather Fritz and his steel IWC Cal.89

Sadly, I don’t remember too much of my grandparents, including Fritz, as they were all quite old by the time I was a young boy. As they were based in New Zealand, and I was in Australia, I didn’t get to see them that much. But I do remember seeing Fritz with his watch in the last years of his life and spending family visits catching up with all four of my grandparents, though those memories are somewhat distant and clouded by the intervening years and my relative youth at the time. If I have one regret, it is not having spent more time visiting them and connecting with that element of my family history. Thankfully, my parents did and can share stories with me.

Fritz was a practical man and always had his trusty wristwatch as well as his Swiss Army-issued pocket knife on hand. Both would get daily use on the farm in New Zealand. Fritz’s prowess with a rifle still came in handy. In NZ, where possums are pests, no possum — or indeed rat — was safe from my grandfather. “I remember Fritz slinging the .22 rifle over his shoulder and taking the dog with him out at night to shoot possums. He always got them!” my mother recalls.

Family heirlooms

Fritz had many hobbies. Aside from being an excellent sharpshooter, he was a master painter and paperhanger by trade. He loved classical music and played the violin. Sometimes he played duets with my grandmother, who was a viola player in the NZ orchestra. He made yogurt and grew his very own vegetables too. His IWC watch always remained on his wrist as a practical memento of the world he’d left behind.

Until one day in his later years, that is, when Fritz was speaking to my mother and suddenly decided that it was time to pass it on. “He gave me his watch from his wrist as I was talking to him one day. It was his daily watch. He wound it at the same time every morning,” my mother recalls. The watch has stayed in the family. So has Fritz’s Swiss Army pocket knife, which is still sharp and is another family heirloom.

My father and an IWC Mark XV

Some years later, in July of 2017, another IWC watch was passed down in the family. This time, it was from my father to me. It happened when I got a job at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and was about to move from Sydney to the remote island state of Tasmania. I had been admiring a handsome watch that my father was wearing and asked to try it on. My father handed me the watch, an IWC Mark XV, from his wrist. I marveled at the solid sensation it left on my wrist and the simple and elegant design. As I was taking it off, my father said to me with some effect, “That’s now yours.” He gave it to me there and then.

To both of us, I think, it was a moment symbolic of me carving my path in the world and leaving the familiar embrace of home for what seemed a distant posting. I have ended up wearing that watch almost every day, and it will always remain that “special watch” to me. This is because it reminds me of that connection with my dad. And that connection was always there, even when I was working in some very isolated and challenging conditions in Tasmania. The adventures I have had with this watch will resonate with me for the rest of my life.

An IWC manufacture tour with special resonance

September, 2023. It’s autumn in Europe, and I’ve come from Australia to visit Schaffhausen. This is a very special moment for me. The folks at IWC have generously opened up their manufacture for a private tour so that my partner and I can see their watch manufacturing first-hand and share that experience here on Fratello. The IWC Manufakturzentrum is the first facility of its kind built by IWC since the original factory was laid down under the stewardship of IWC’s American founder Florentine Ariosto Jones in the 1870s. The expansive use of glass and open spaces creates a warm, welcoming space. This being my first tour of a watch factory, the building is much different than I was expecting, giving off an inviting, home-like feeling combined with a stark, seamless modernity.

A large model of the IWC perpetual calendar module created by Kurt Klaus, which had its debut in 1985, sits above the reception. IWC’s CEO Christoph Grainger-Herr (above), a trained architect, helped design the building, which took 21 months to complete. The 140m-long by 62m-wide structure provides huge swathes for all aspects of production, including future expansion. Walking through the L-shaped hallway to the factory, it is striking how open the production space is.

A watch lover’s dream

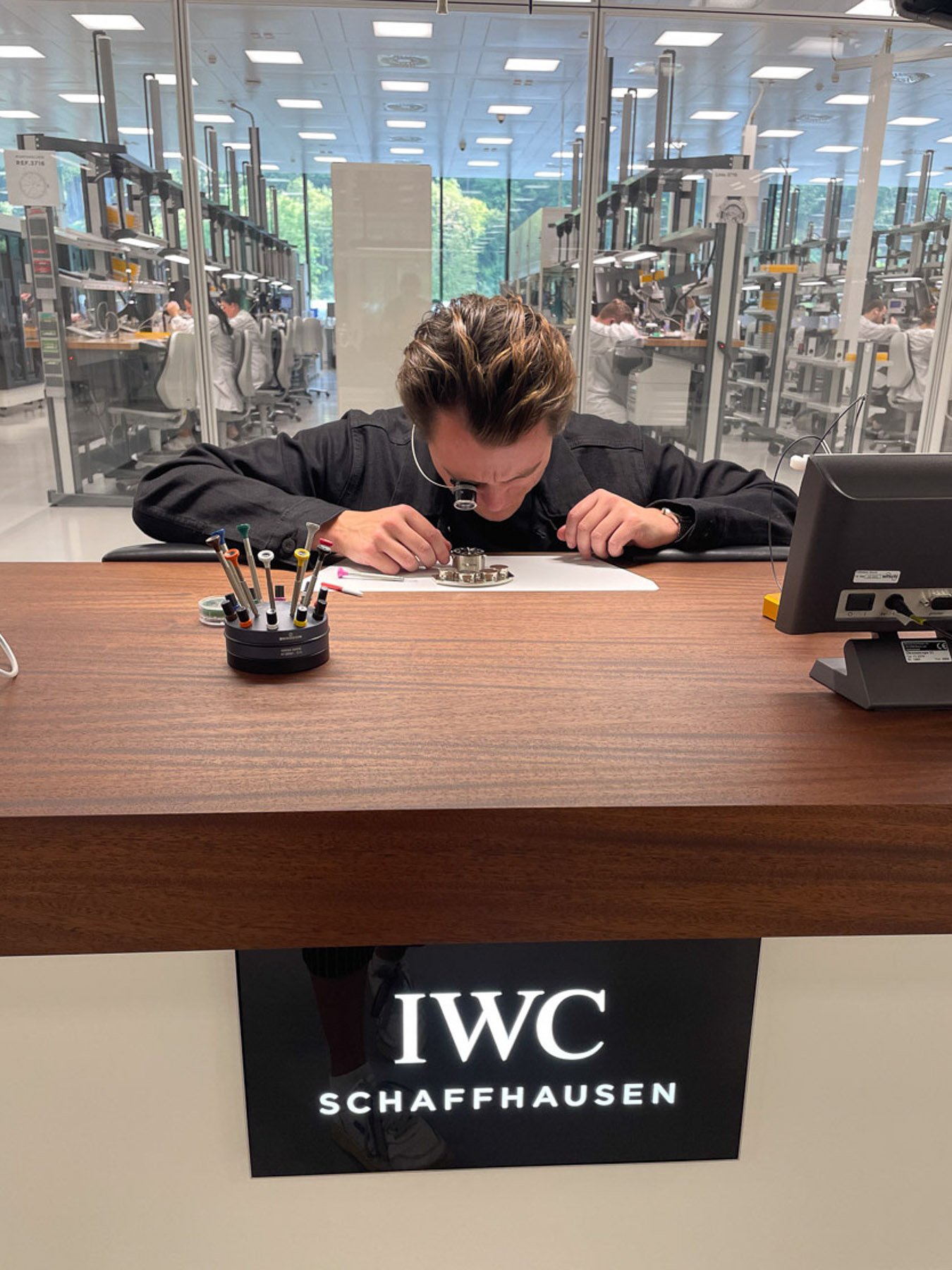

The hum and whir of machinery dominate small in-between spaces as watchmakers quietly apply their craft. It is in this large area where movements are made. Machines mill, cut, and turn parts in an impressive array of industrial efficiency and precision. Workers then apply their years of experience turning these raw elements into things of beauty and craftsmanship. There is a dizzying mix of centuries-old knowledge in practice combined with modern technological wizardry.

Each caliber has a designated production line following a meticulous process. Components are decorated, and jewels are set into bridges and plates as watchmakers begin to breathe life into the movements. I was quickly absorbed by the focus on engineering here. I’m shown screws that are only twice as thick as a piece of paper (and, therefore, impossible to photograph). This is the stuff that watch lovers dream of.

It’s all in the details

In one corner, standing out amid the state-of-the-art machinery is an old machine no bigger than a desk lamp. It is from 1903, and it is what the watchmakers use to apply perlage to this day. I got to sit down and try to apply perlage to a piece of test metal. It’s much more difficult than those using the machine make it seem. Use too much force, and you’ll gouge the surface; use too little, and you’ll be left with ugly rings. On my third attempt, I got something close to respectable, and it felt wonderful.

Further down and into the basement is where case manufacturing takes place. We go down an elevator and see row after row of raw materials. It is here that stainless steel, various types of gold, titanium, platinum, and bronze are turned into cases. It is also where IWC’s Ceratanium cases are manufactured. In one corner, a case finisher is completely absorbed in her work, finishing the case of what looks to be a Mark XX Pilot’s Watch amid the rhythm of a busy work floor. All of the watches here, I am told, are tested to maintain an accuracy of +0–7 seconds per day. This is so that no one will ever be late, only early, if they have an IWC tested to factory specifications.

What next for IWC?

Watch brands each have a unique identity. This is not only what a watch company might want you to think about its products and brand story but also (and more importantly) what we, as consumers, consider to be the watch brand’s identity. In other words, a watch brand’s marketing identity is a bit like your social media profile; some bits are true, but a lot of it is simply how you want the world to view you. To continue this analogy, the customer/enthusiast/consumer’s impression, then, is much more similar to a loved one’s perspective of you. It’s a personal connection. Tudor’s impressive marketing had nothing to do with the watch choice I made for my 30th (the Tudor Black Bay Fifty-Eight in blue, which I wrote about here). What did convince me was the sizing, utility, and design.

IWC’s marketing with Formula 1 racer Lewis Hamilton has nothing to do with my love of the brand. IWC is a rare beast in the watch world when it comes to identity because, in truth, it has multiple identities. The brand is the quiet achiever, a creator of magnificent tool watches that participated in major conflicts or just everyday use in difficult conditions, and a manufacturer of Haute Horlogerie complications and elegant craftsmanship. In my mind, IWC will always be my “family” brand, even if nothing in its modern lineup speaks to me as strongly as Fritz’s Cal.89 or my father’s Mark XV. But I hope that, one day, IWC will release a watch that speaks to me in the same way and that I, too, can pass it on.

Final thoughts

What was wonderful to see at the IWC manufacture was the clear sense of pride that the watchmakers and staff have in their work. This is an industry of attention to the small things, the details. I could see the satisfaction on one man’s face as he looked over what would one day be someone’s IWC timepiece, this one a Pilot’s Watch Chronograph.

For some of us, there is a special connection to a watch manufacturer through family memories or personal experiences. As you can understand, I have this connection with IWC, so visiting the manufacture was special on several levels. First of all, it was the first tour of a watch factory that I had ever experienced, which was exciting in and of itself. But the interesting mix of modernity and age-old craft also felt like a connection from Fritz’s era to my father and now to me in this moment, coming for my first visit to Schaffhausen. I feel very fortunate that I could share this moment with my partner and the watch that my father gifted me.

The visit to Schaffhausen was over all too quickly. Before I left the IWC factory, I took a quick photo wearing my father’s watch outside the new facility. It was an emotional moment. This was a visit almost 80 years in the making and one for which I am deeply grateful to the IWC team for accommodating.