Behind The Scenes In Geneva — Visiting The Craftspeople At Laurent Ferrier And F.P.Journe

I have written about watches for several years now, and like most of you, I am more enamored by the pure craftsmanship than time-telling itself. Sure, a watch has a base function as an instrument. But we have everything from phones to coffee machines telling us how time flies. What makes my heart sing is the mix of time-honored traditions and high technology, and going behind the scenes in Geneva made it all clearer to me.

To me, what’s inside the case is almost more important than the actual function of a watch, not to mention the time it takes to finish and assemble and finish a piece of Haute Horlogerie. Even mid-range mechanical watches require a human watchmaker’s touch, and that is more fascinating to me than COSC-rated chronometry. At this year’s Geneva Watch Days, I got the chance to go deep behind the scenes at the Laurent Ferrier atelier and F.P.Journe’s new facility for the Cadraniers and Boîtiers de Genève.

Behind the scenes and holding my breath

For this story, I got unprecedented behind-the-scenes access, first as a guest in the charming atelier of Laurent Ferrier. This involved handling my camera while holding my breath just an inch away from an unfitted tourbillon. The next day, after digesting the impressions while trying to balance a tight schedule of meetings, I got an invitation from F.P.Journe to the brand’s new four-story facility. There is also a link between Ferrier and F.P.Journe, which was unknown to me and will become apparent later. While one is small-scale and the other a high-tech facility, both embody the same passion for keeping the flame of watchmaking alive. You might think we live in uncertain times, but Journe’s C&B had its ribbon cut this summer, and Laurent Ferrier also plans to move to larger premises. These are telling signs of watchmaking’s resurgence and the power of the independents.

Inside the heart of Laurent Ferrier

As a small-scale manufacturer with a portfolio of grail pieces, Laurent Ferrier’s 17 employees work within a converted family home. And what struck me was the beguiling blend of perfectionist craft and a big-hearted spirit. Laurent Ferrier’s head of sales Robert Bailey hosted me and told me about this unusually charming atelier and its workforce. “Currently, we have 13 watchmakers and four decorators. As of October 1st, we will have 15 watchmakers and 5 decorators.” As you can see from the image above, Ferrier’s watchmaking home is pretty far removed from the lab-like facilities of Rolex, but I find that a big part of the appeal.

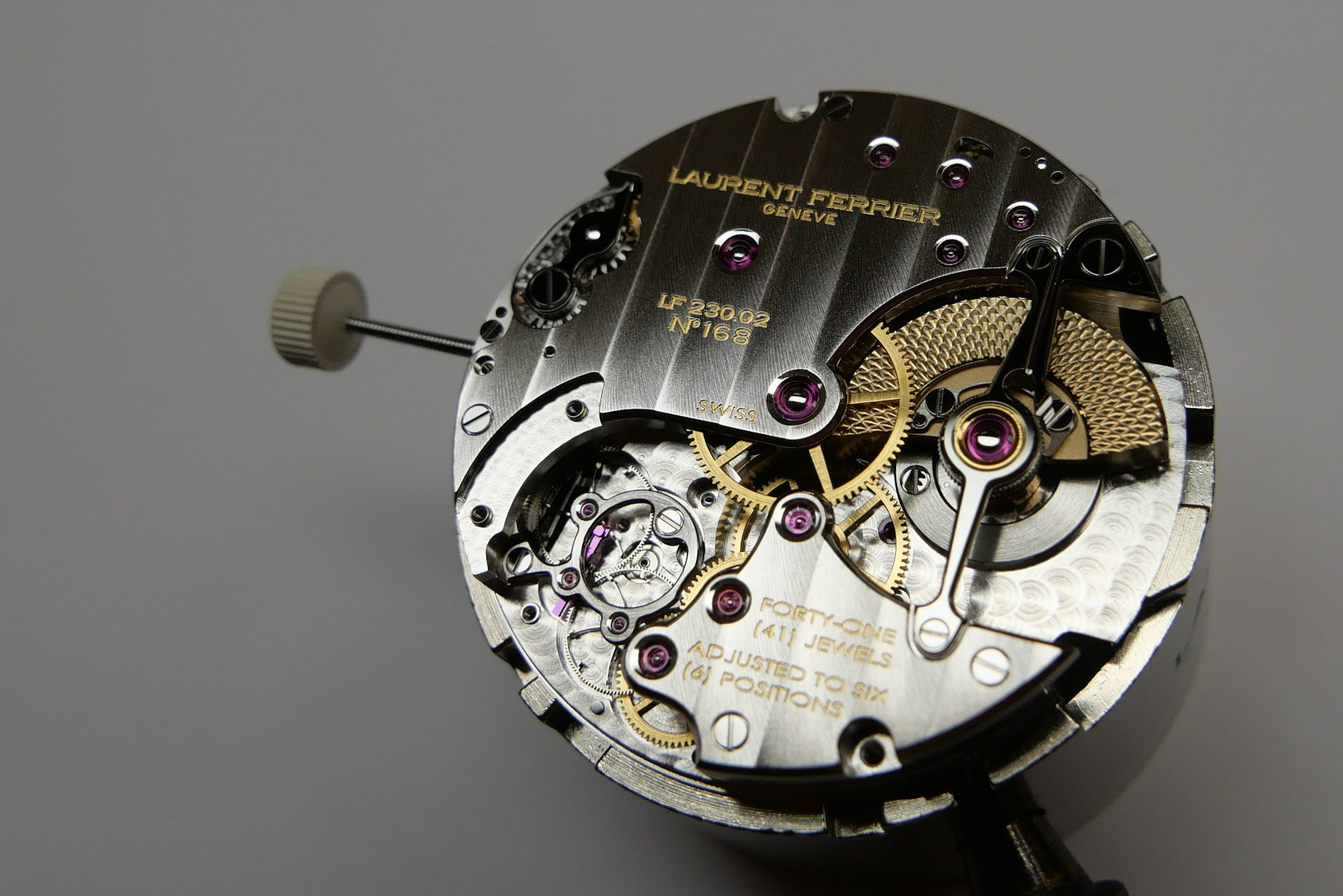

The intrinsic detail of the micro-rotor movement

The main focus during my visit was the assembly of Laurent Ferrier’s highly lauded micro-rotor movement. Within the tougher Sport Auto, you notice its modern yet traditional details even more. It is also a sharper, modernist approach than the FBN229.01 movement in the timeless Classic Micro-Rotor – and Square iteration with its pebble-smoothness. Robert told me about its development, including how long it took: “…about two years for the first version. There is, of course, a continuous improvement cycle on all of our calibers, so we have worked on it quite a bit since it was launched as well!” There is a passion within the workshop that comes across through the warm reception, and it’s contagious.

Meeting the workshop manager Basil and watchmakers like Alexandre only made it clearer. The intimate atmosphere of quiet perfectionism within the atelier underlines why collectors choose independents over the aloof big brands. For me, seeing the Sport Auto’s Calibre LF270.01 micro-rotor movement outside of its case made its features even clearer. As I held it between my thumb and forefinger in the image above, I got a closer look at one mid-assembly. And you can see the delicious perlage on the mainplate where the micro-rotor will get its final positioning.

Worth the wait

And for once, the question of accessibility is not an elephant in the room. You’ll just require some patience. I talked to Robert about the assembly time of a watch and the actual production time after ordering. He told me, “Total work time on a watch is about two weeks. This includes the decoration of the components and assembly. Assembly takes about a day, and encasing takes about half a day. Consider this included in the two weeks. That makes up about eight and a half days of decoration, a day of movement assembly, and a half day of encasing. On top of all of this, there is testing.” Robert also told me that all new orders today are being confirmed for 2025. This is pretty good considering that some brands like Grönefeld have closed their books for this year.

Obviously, I had a look at the tourbillon caliber LF619.01 within the Grand Sport. And yes, the intriguing fact that the Tourbillon is not visible on the dial makes it an even more tempting proposal for me.

I also wanted to know whether Laurent Ferrier is planning to expand since rumors tell of a planned move. Robert tells me, “The LF way is slow and steady, so yes, we will increase by 100 or so watches next year. But we will also bring more processes in-house to control the quality, so the team will be growing. This will mean we need to find a new location, which is still a work in progress.”

Cadraniers et Boîtiers de Genève

A contrast to the intimate feeling of the Ferrier workshops, I was lucky enough to have a solo tour of the new high-tech Cadraniers et Boîtiers de Genève facility in the company of a member of the F.P.Journe team. There is a link to Laurent Ferrier here, but what struck me first was the reason for the new building and its impressive lab-like atmosphere. The workshops have been optimized for the best natural lighting and are accurately controlled for humidity and temperature.

But F.P.Journe has not opened this facility to ramp up production numbers. Instead, the focus is on quality control in all aspects and not even just for the brand itself. The link with Laurent Ferrier is in the dials, which come from Cadraniers de Genève. The in-house expertise makes this F.P.Journe arm a supplier of the most intricate dials for other brands like Vacheron Constantin as well as a few others, mostly kept secret. But high-tech as it may be, this is a hub for craftsmanship and finishing skills emanating from the previous centuries.

High-tech with a soul of craftsmanship

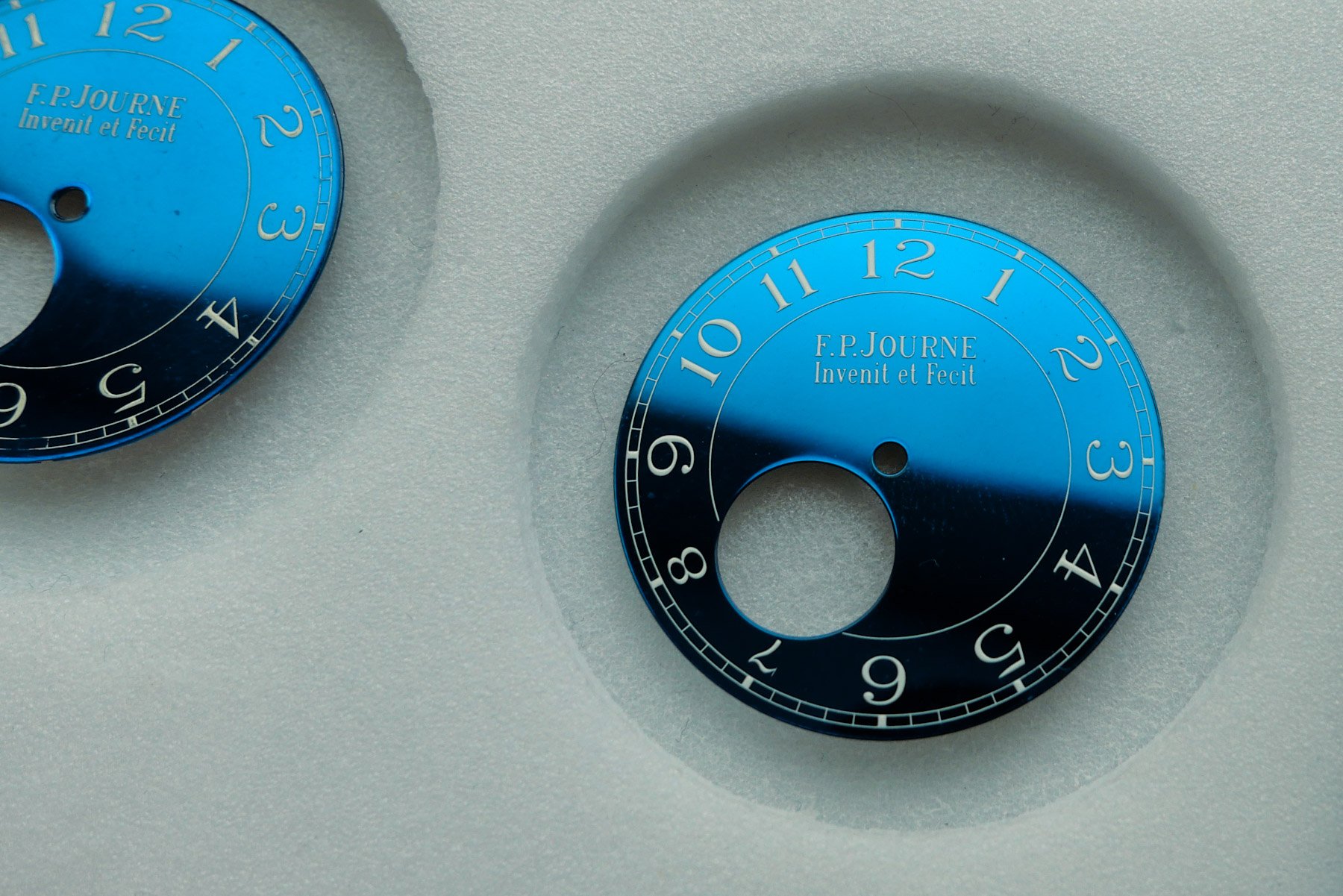

For the non-francophones among you, the “Cadraniers et Boîtiers de Genève” name refers to dials and cases, respectively, while F.P.Journe’s atelier in central Geneva produces the intricate calibers. The total vertical integration of the company is as impressive as the small details, but with F.P.Journe, the dials come first. Indeed, when developing a new reference, François-Paul Journe always starts with a dial design, not a case or a movement. This is far more complex than using a newly designed movement as the starting point. However, it does lead to some stunning results, such as the deep, chromatic blue of the Chronomètre Bleu, which, except for the Élégante, is perhaps the perfect entry ticket to the brand.

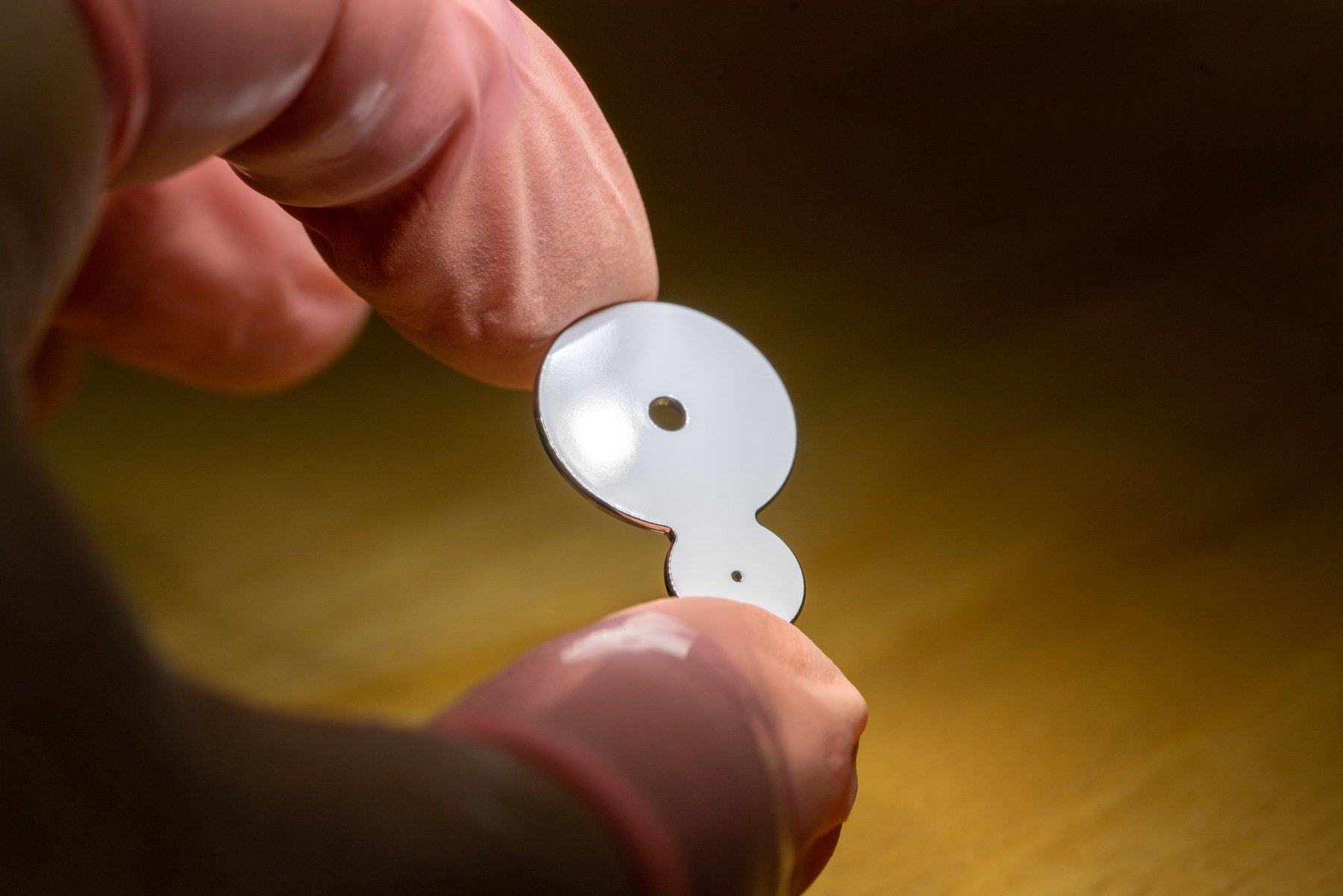

When a dial is so much more

Expanding on the dial of the Chronomètre Bleu, F.P.Journe’s head of press relations tells me more: “There are many stages, starting with polishing. It’s the most delicate part, as it produces heat that can cause the dial to warp. After delicate machining stages, successive stages of varnishing and lacquering follow, with several pauses in a high-temperature oven to fix the paint. For a series of 100 dials, only 15 to 20 are left at the end. This is mainly due to the very thin base and many manual steps that require great dexterity. François-Paul doesn’t want to change this thickness because he wants to keep his watch as thin as possible and is prepared to accept this high level of waste.”

The case itself is made from tantalum, a notoriously challenging metal to work with. F.P.Journe even manages to produce this rare-metal, all-polished 39mm case in-house. Its heavier, precious-feeling material makes for a perfect frame around the blue dial, and FPJ imbues it with some of the best polishing I’ve seen.

Do you see this immaculately snailed small seconds register? For the Chronomètre Bleu, it is manufactured separately and fitted to the back of the dial. The glass-like dial itself has multiple polished layers of lacquer that give it remarkable depth. It is not like Grand Seiko Urushi but like blue chrome, turning a chameleonic black at certain angles. My favorite detail, though, is the fact that the “7” and “8” numerals are printed smaller next to the seconds register instead of cut off by it.

A diamond-set stunner

Due to the nature of the split F.P.Journe manufacture, I didn’t get to see the movement. For the Chronomètre Bleu, it is made almost entirely of solid pink gold. When it comes to the cases, though, I had a closer look at one that blew me away. It’s not my usual cup of tea, but this got to me. The fully gem-set version of the Tourbillon Souverain has the classic rounded Journe case with a twist. Watching the final polish up close with the smooth case accentuated by 93 baguette diamonds tugged at my heartstrings. Would I have it on my wrist for a black-tie dinner? That is an affirmative, though my wife might catch on to our sudden mortgage increase.

During my visit, I saw a few dial secrets that I am not at liberty to divulge. But I can attest to a few must-sees, such as some of the Metiers d’Art dials of prestigious brands on the outside of their cases. These minuscule paintings on 30-odd-millimeter canvases will put most regular-size paintings to shame, let alone a mere dial. Honestly, that was only one of many aspects that made me want to train as a watchmaker.

Fratelli, I’m sure I could write a lot more about these two visits behind the scenes in Geneva. But I just wanted to give you a taste, even if it makes you desire more watches. Let me know your thoughts on accuracy versus handcrafted beauty in the comments.