GMT Watches 101: Caller Versus Flyer (Or “True”) GMT Explained

School bell’s ringing, Fratelli! Welcome to GMT Watches 101. We keep talking about caller versus flyer GMT watches, and many people even habitually refer to “true GMTs”. We happily assume that everybody knows what we’re talking about, but that’s probably not the case. Sometimes we need to take a step back and cover the basics. So let’s have a look at the different ways GMTs are executed.

Let me potentially save some of you a little time before we start. If you know the difference between caller and flyer GMTs, you could skip this article. If you’re not quite sure though, keep reading. Also, if you want to dive a little deeper into some technicalities, make sure to stick around!

Caller versus Flyer GMT: What is a caller GMT?

The purpose of a GMT watch is to offer the convenience of tracking time in two or three time zones. Wait, three? We’ll get to that later. For now, let’s focus on the first two. As on nearly any analog watch, the first time zone is displayed with central hour and minute hands. The second one is usually pointed out by an additional hand. This hand usually goes around the dial once every 24 hours rather than 12. So far, there are no differences between caller and flyer GMTs.

A caller GMT, specifically, features a GMT hand that can be independently set. If you change the main time, the GMT hand rotates as well, albeit at half pace. This has implications for how you use the watch. You set your local time on the main handset. You set the GMT hand to whatever other time zone you want to track.

So, why is this a “caller” or “office” GMT? Well, because it works perfectly if you have business contacts abroad. Let’s say that you are here in The Hague, and you are working on a deal with a New York-based partner. Without affecting your local Dutch time, you can set your GMT hand to six hours earlier. This way, when you want to call your partner at 4:00 PM, your watch shows that it is 10:00 AM in NY. It’s perfect for working from the office, calling people — hence “office” or “caller” GMT.

Caller versus Flyer GMT: What is a flyer GMT?

Functionally, a “flyer” or “traveler” GMT is the exact opposite. One crown position sets the local time and the GMT hand simultaneously, the latter at half pace. The other crown position, however, sets the local hour hand separately. This, again, has implications for how you can most easily use the watch.

In this case, you set the GMT (24-hour) hand to your home time (or to Greenwich Mean Time if you prefer to use that as a reference). You set the main handset to local time (wherever you are). When you hop on a plane to a different time zone, you can easily jump the local hour hand to your target time zone without affecting home time or the minute hand.

Again, let’s say you live in The Hague and are leaving to fly to New York at 4:00 PM Dutch time. Your local hour hand points at 4 and the GMT hand at 16. In other words, they are both set to home time, with one on a 12-hour scale and the other on a 24-hour scale. As you touch down in New York eight hours later, you change your local time to 6:00 PM. Your GMT hand is now pointing at 24, indicating that it is midnight in your hometown. This approach, in short, is optimized for traveling. That is why we call it “traveler” or “flyer” GMT.

Why is it sometimes called a “true” GMT?

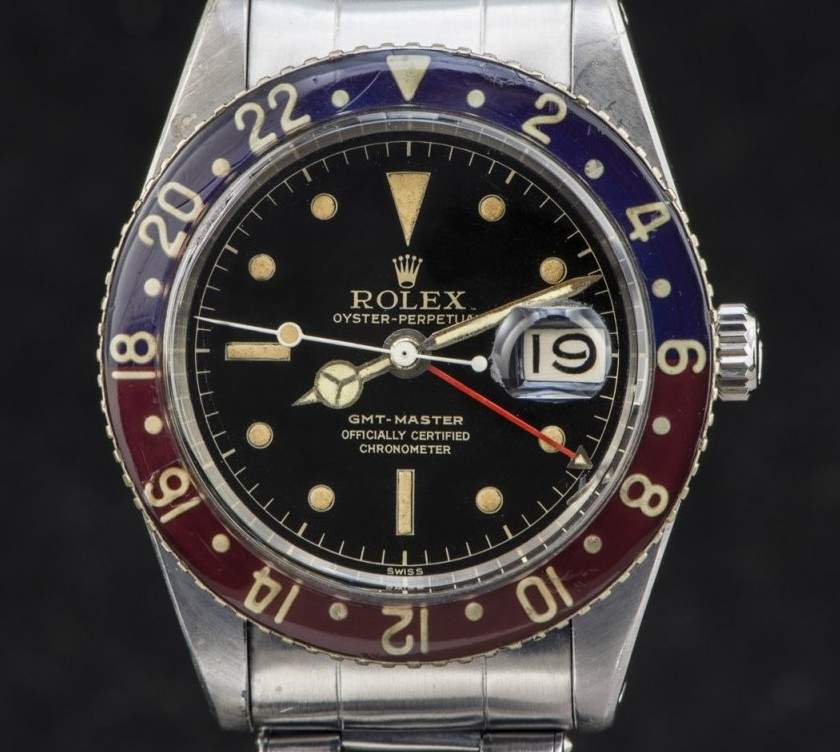

Many in the watch community refer to the latter approach as a “true” GMT. This is because, in their eyes, it was developed for pilots, so it “must” be the original approach, right? Well, unfortunately, that’s not entirely true. Historically speaking, the first watch to bear the “GMT” distinction was the Rolex GMT-Master ref. 6452 in 1954. Crucially, this watch did not feature an independently adjustable 12-hour hand. In fact, it didn’t have any independent hands at all! The Rolex caliber 1065 within did indeed have a 24-hour hand, but it was “enslaved” to the 12-hour hand at all times. Therefore, to read the time in different time zones, pilots would have to adjust the rotating bezel.

Believe it or not, it wasn’t until 1983 — a full 29 years later — that the first GMT-Master II ref. 16760 “Fat Lady” debuted. This watch housed the Rolex caliber 3085, which was the first movement in the history of the model line to feature an independent 12-hour hand. That, we feel, is the crucial point.

Undoubtedly, this newly adjustable hand provided superior functionality for pilots and travelers. Having demonstrated this, Rolex discontinued the GMT-Master (then ref. 16700) altogether in 1999. However, if “true GMT” means “the first” or “the original” approach, then, historically speaking, it is a misnomer. That is why we at Fratello try our best to avoid using the term in our articles.

For better or worse, the term remains popular

Perhaps unaware of the historical context, many people in the watch community continue using the term “true” GMT. That said, with the iconic status of the Rolex GMT-Master II looming large, many may also equate the adjustable 12-hour hand with “the real deal.” This notion is emphasized by the fact that many more affordable GMT watches are of the caller style. Not too long ago, you needed to spend a significant sum to get a flyer GMT.

Luckily, that is no longer the case. Miyota, for instance, launched the affordable flyer GMT caliber 9075 in 2022. You see it becoming more popular in the microbrand space now. The Traska Venturer, for instance, is priced at US$720. Not too long ago, that would have been only been able to buy you a caller GMT.

So, in summary:

- A flyer, traveler, or “true” GMT allows one to independently set the local/12-hour hand.

- A caller or office GMT allows one to independently set the GMT/24-hour hand.

Tracking a third time zone with a bezel

This is where we depart somewhat from the main topic, but it might be helpful to elaborate on what GMT watches can do. The classical template for a GMT watch has always featured a rotating 24-hour bezel. Back in the early days, with the Rolex GMT-Master’s enslaved 24-hour hand, the bezel was necessary to track two time zones. These days, however, thanks to independently adjustable hands, the bezel can be used to track a third time zone.

This is easiest if the watch has 12-hour indices as well as two sets of 24-hour markings. A good example is the Grand Seiko SBGE275 flyer GMT above. As you can see, the dial has 12-hour indices, the rehaut has a 24-hour scale, and the rotating bezel has 24-hour markings as well. With this watch, you can set your home time by pairing the GMT hand with the scale on the fixed rehaut. You can adjust your local/travel time via the 12-hour hand, and then you can also rotate the bezel to display a third time zone in a 24-hour format.

The Rolex GMT-Master II doesn’t feature 24-hour markings on its dial or rehaut. Consequently, you cannot read three time zones simultaneously. You can, however, first adjust the GMT hand to local time, next set the local hour hand and bezel to Greenwich Mean Time, then lastly rotate the bezel to temporarily show a third time zone. You just need to know that time zone’s offset with Greenwich Mean Time.

Mike Stockton’s vintage Glycine Airman Special, featuring a 24-hour bezel, a 24-hour dial, and a “tailed” hour hand

The Glycine Airman offers another approach

It’s also worth mentioning the Glycine Airman here. This three-hand watch debuted at the end of 1953 — yes, predating the GMT-Master — and showed two time zones simultaneously. It featured a 24-hour dial layout for the main time and a rotating 24-hour bezel for an additional time zone. If you wanted to instantly read the main time on a 12-hour scale, you were out of luck. That was until 1957 when Glycine added a “tail” to the hour hand. With this, you can read the main time on a 24- or 12-hour scale. Of course, you can also still rotate the bezel to display a second time zone. Actually, you can even read three time zones since the main hour hand alone indicates two that are 12 hours apart (Honolulu and Helsinki, for instance).

This modern reissue of the Airman is a caller GMT, featuring not three but four hands. The independent GMT hand can display two time zones simultaneously thanks to the 24-hour markings on both the dial and the rotating bezel. The main hour hand now rotates on a 12-hour scale, corresponding to the lumed indices. However, once again, if you live in The Hague, you can also read the 12-hour time in New York (-6 hours) with that hand’s pointy tail. That’s a total of four time zones. Not too shabby, I’d say.

Caller versus flyer GMT: which to choose

Now that you know the difference between caller and flyer GMTs (and a whole lot more), the question is: which is for you? Naturally, it makes sense to follow their intended use. If you travel a lot, a flyer GMT makes more sense. If you work from home for international clients, a caller makes sense.

Don’t think, however, that you cannot use a caller for traveling and vice versa. As with anything, it is a matter of getting used to it. Our own Mike, for instance, travels a whole lot more than me, and he always emphasizes that the “caller versus flyer GMT” debate is greatly exaggerated. So, Fratelli, Mike doesn’t care. Be more like Mike.

I am happy to see that both options are now becoming available to a broader range of segments. Whichever you prefer, it is always nice to have a choice.

Which do you prefer, flyer or caller GMTs? Let us know in the comments below.