How My Grandfather’s IWC Caliber 89 Is A Connection To A Bygone Era

Watches can be a deeply impersonal affair. The rise of social media hype, luxury exhibitionism, and wristwatch “flexing” is very different from what watches once represented. It wasn’t all that long ago that they were simple time-telling tools with a little style thrown in (perhaps even some panache). This article is a celebration of watches as deeply personal objects, indeed, treasure houses of memories and emotions.

My grandfather Fritz’s choice of time-telling tool is emblematic of the era in which he grew up. Born in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, Fritz Meister served as a member of the Swiss military as a sharpshooter during WWII. This was a period when Switzerland faced the real prospect of an invasion by Nazi Germany. That plan went by the name of Operation Tannenbaum and would have seen the deployment of 11 German divisions and as many as 15 divisions from Fascist Italy in an attack on the tiny country. This would have represented anywhere from 300,000 to 500,000 men participating in the invasion force.

The day Schaffhausen was bombed

That invasion never took place, though, as Nazi Germany turned its gaze to other theaters of war. Even so, WWII deeply affected Switzerland, particularly the locals of the town of Schaffhausen. On April 1st, 1944, 15 B-24 Liberator bombers from the US Air Force dropped 371 incendiary and high-explosive bombs on the town of Schaffhausen. They’d mistaken Schaffhausen for the German town of Ludwigshafen am Rhein near Mannheim.

According to an article that refers to an interview with one of the bomber crew’s squadron commanders, new radar technology had malfunctioned, and weather hampered a visual reference to make any corrections. This meant the US Air Force pilots had gotten completely and hopelessly lost. What worsened this was the fact that as the formations of planes moved from France and into Germany, they ran into cloud cover as high as 21,000 feet (6,400 meters). At this height, their radar should have saved the day, except it malfunctioned. The US Air Force pilots resorted to using guesswork without any visual reference to terrain to work with. The lead navigator had to rely on prebriefed estimates of winds to carry out his dead-reckoning type of navigation.

Schaffhausen in 2023

A dark day for Schaffhausen

The educated guesswork that day proved deadly to the Swiss town. At around 11:00 AM, bombs started landing everywhere across the town, ripping through stone and turning buildings into rubble. Dozens died within a matter of seconds (some estimates put it as high as 60). Hundreds also became homeless. Fire crews rushed to put out the fires. At the International Watch Company (IWC) factory in Schaffhausen, a bomb smashed through the rafters but failed to detonate. The flames from incendiary ammunition exploding nearby threaten to engulf the building. Members of the watch company’s fire brigade just managed to put out the flames before they spread. The level of destruction is clear in these remarkable historical images.

As I explained in this Fratello feature about a visit to the IWC Museum and factory, my great-grandfather Jules Meister was killed that day. He is commemorated along with the other 39 individuals officially killed in the 1944 American bombing of Schaffhausen. According to his grandson Gerry Meister, he was standing on the steps of the post office when “he saw the bombs dropping. He ran for safety into the underground passage leading to the railway station. The post office was spared, but the station and the underground passage were destroyed.” On this map, you can see the locations where civilians were killed, including Jules.

My grandfather’s IWC Caliber 89

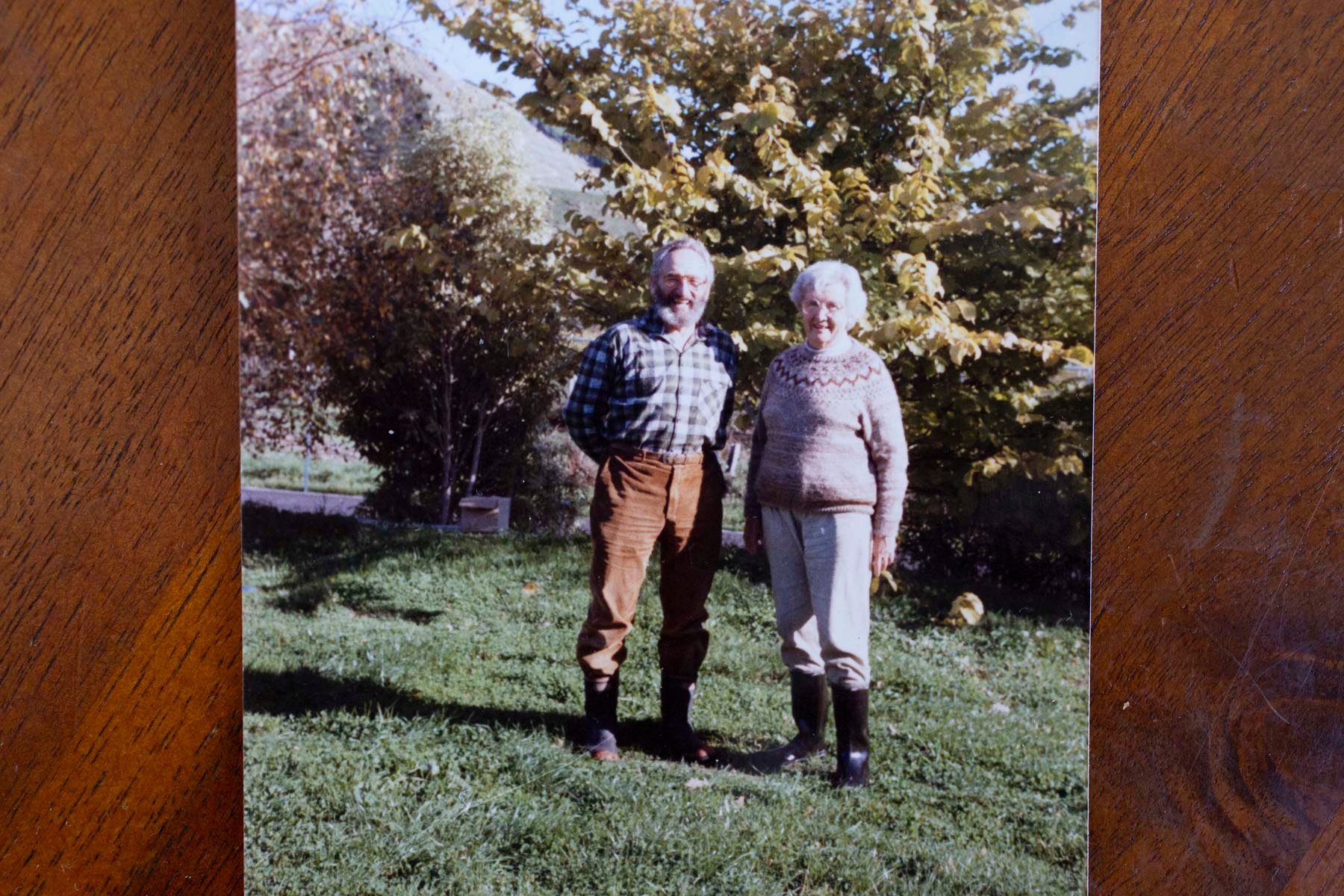

I sometimes imagine if my grandfather’s decision to return to his hometown, where Jules died, was a process of coming to terms with this loss. Unfortunately, I never got to ask him. By the 1960s, Fritz had moved to New Zealand to create a new life for himself. That was where he met my grandmother Wendy. At some point during the 1960s, they both visited Switzerland, where he bought the watch I am looking at today, the IWC Caliber 89. Now, it’s not common for a watch to be referred to simply by its movement, but for many IWC collectors and enthusiasts, the IWC Caliber 89 stands for essentially any dress watch featuring the caliber.

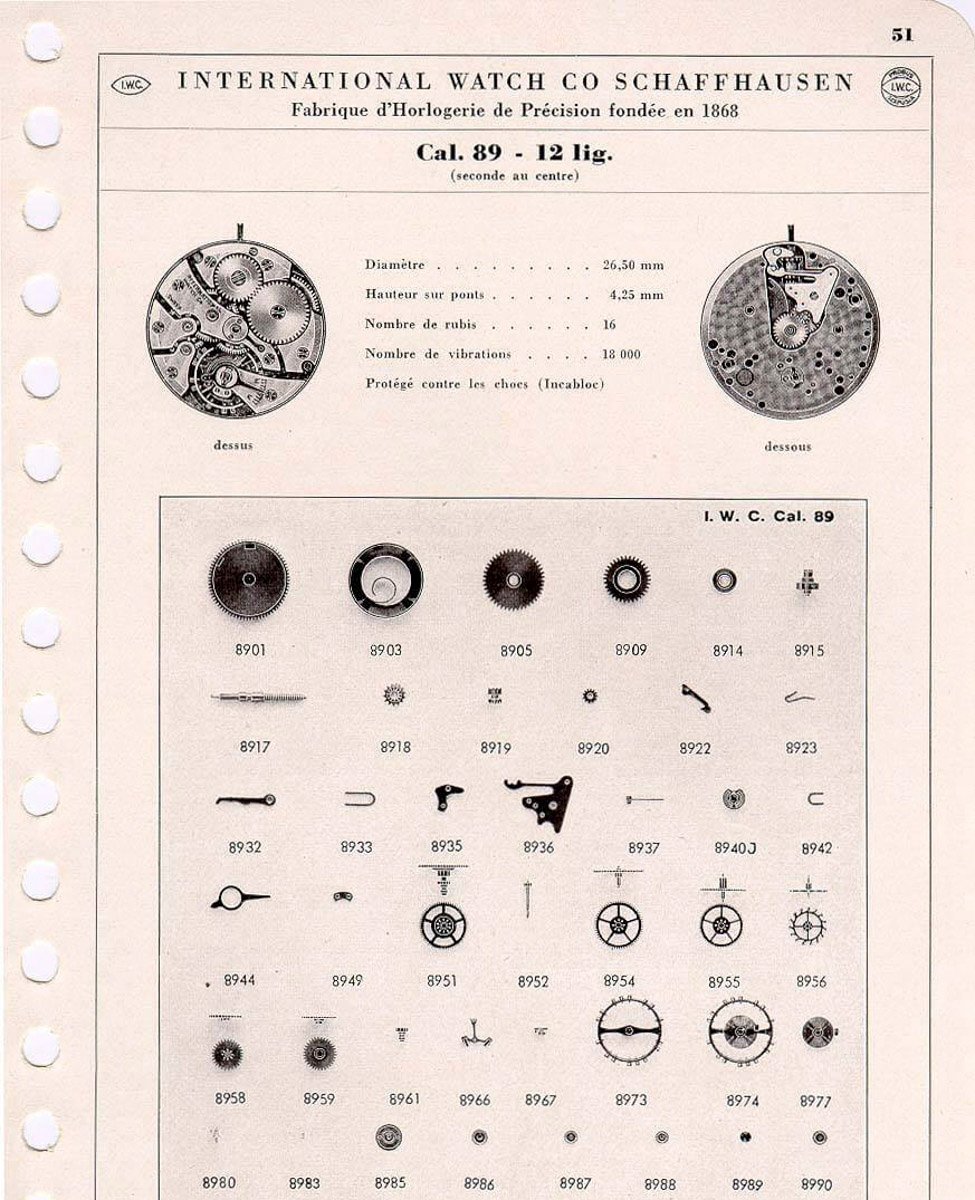

Interestingly enough, the IWC Mark 11 pilot’s watch also housed Caliber 89. It had been designed as a more durable manually wound movement with center seconds and an upgrade to the sub-seconds Caliber 83. Today, Caliber 89 is considered one of the greatest watch movements of the 20th century. Fittingly, the IWC Mark 11 emerged out of the embers of WWII. In 1944, IWC launched its first W.W.W. (Watch, Wrist, Waterproof) for use by the British Ministry of Defence.

A movement success story

These watches came to be known simply as the Mark 10. They were characterized by the sub-seconds (of Caliber 83), broad arrow insignia of the British MoD, and simple Arabic numerals. In 1946, Albert Pellaton (technical director of IWC at the time) introduced the new Caliber 89, and it was first put into production with the upgraded IWC Mark 11 in 1948 for the MoD. The IWC Caliber 89 was so successful that it had a production run from 1946 to 1979. It was famous for being a highly robust and straightforward movement. Caliber 89 has a thickness of 4.25mm and a power reserve of around 35–36 hours when fully wound. It measures 27.1mm across and includes 17 jewels, an overcoil balance spring, and the option of a hacking function for the central seconds hand.

Though this last feature was not always present, it was very useful in military applications. Caliber 89 also beats at an 18,000vph frequency. Known and respected by watchmakers the world over, it is a relatively simple movement. However, the bridges and cocks are of renowned high quality and finished with Geneva stripes. However, this movement is not known for its ostentation but, rather, its durability.

A military movement in an elegant package

IWC’s Caliber 89 has particularly overbuilt steady pins to secure the bridges into the plate of the movement. They were also thicker than the norm at the time. The use of Incabloc shock protection also provided an added degree of robustness to knocks and bumps. Oversized screws with particularly long threads showed the movement’s tool-watch roots.

IWC decided it had a winner on its hands and put the Caliber 89 into a host of elegant dress-watch cases, from sizes of around 34mm to as large as 37mm wide. There was an enormous variety of case designs, lug designs, and even the choice of metal used (gold, or steel). This variety creates a wonderful opportunity for enthusiasts because there will be a case, dial, and lug design to suit almost any taste.

My grandfather’s Caliber 89

It seems my grandfather Fritz had fantastic taste. He decided on a relatively simple design when he visited the IWC factory in Schaffhausen in the 1960s to purchase his watch. The watch in question has a lovely clean white dial, beautifully sharp indices that create a gorgeous light play in the sunshine, and a simple lug design with drilled holes.

“Simple elegance” sums up this watch for me, and it seems appropriate for the man who first bought it and wore it every day for more than five decades before it found its way to my mother. Scratches mark the Plexi, but Fritz always had the watch served in Schaffhausen when it needed any mechanical upkeep.

Another artifact that survived the 20th century is Fritz’s Swiss Army knife. This was issued to him during his time as a soldier in WWII. It is still incredibly sharp.

Concluding thoughts

There is something wonderful about an era when objects were excellently made strictly for their intended purpose. Watches were made with a commitment to the details and quality because they were critical time-telling tools. This spirit of building things to last so their original owners can pass them on one day is probably the best element that attracts me to this hobby. I may not have spent a great deal of time with Fritz when he was alive, but at least I can look down and admire this humble and beautiful little watch and remember him, my grandmother, and the experiences the watch must have seen.

What about you, Fratelli? Is there a watch you’ve inherited from a relative? What was it? Let me know in the comments. I’m looking forward to reading them.