How Watches Work: What Is Guilloché?

A great watch dial is made beautiful by techniques such as guilloché. Created by skilled artisans called guillocheurs, who pour thousands of hours into their work, guilloché is the art of engraving fine and intricate patterns on metal with the use of a rose engine, straight-line engine, or brocading machine. Traditional guilloché methods are slowly dying out, as computer automation paves the way for cheap and precise but cold detailing on watches. Guilloché, once a thriving art form taught in dedicated schools, is now used only by a few specialist brands.

Guilloché is created by operating the cranks of the machine to orientate the dial of a watch. The guillocheur then applies pressure to the dial against a cutter. Varying the pressure creates different effects. This process applies precise lines which form specific patterns. These patterns are meticulously planned out by the guillocheur beforehand.

The history of guilloché

Guilloché was popularised on pocket watch dials by Abraham-Louis Breguet in the late 1770s. At this time, Breguet was making unique pieces with guilloché dials for his buyers. Vacheron Constantin is another early maker of guilloché dials on their pocket watches. Breguet and Vacheron Constantin have been making guilloché dials throughout their history. Between 1896 and 1932, the School of Applied Industrial Arts in La Chaux-de-Fonds is conducting classes on guilloché with up to ten students at a time. Notable alumni of the engraving school are Fernand Droz (a founder of Jacquet Droz) and Henri Perregeaux (Girard-Perregaux watch manufacturing family). However, due to war, classes see a lack of enrolment and stop completely as guillocheurs become ammunition makers.

The art is revived partly by Audemars Piguet in the 70s with their Royal Oak dials. The Clous de Paris or hobnail pattern on the Royal Oak was created by Roland Tille. The Royal Oak pattern is made using a brocading machine. As guilloché lost its popularity, Vacheron Constantin continues to practice the art. Nowadays, many guilloché-patterned dials are made by Computerised Numerical Control (CNC) machines. CNC is a quicker process than hand guilloché as pre-programmed software controls production equipment without the need for human intervention.

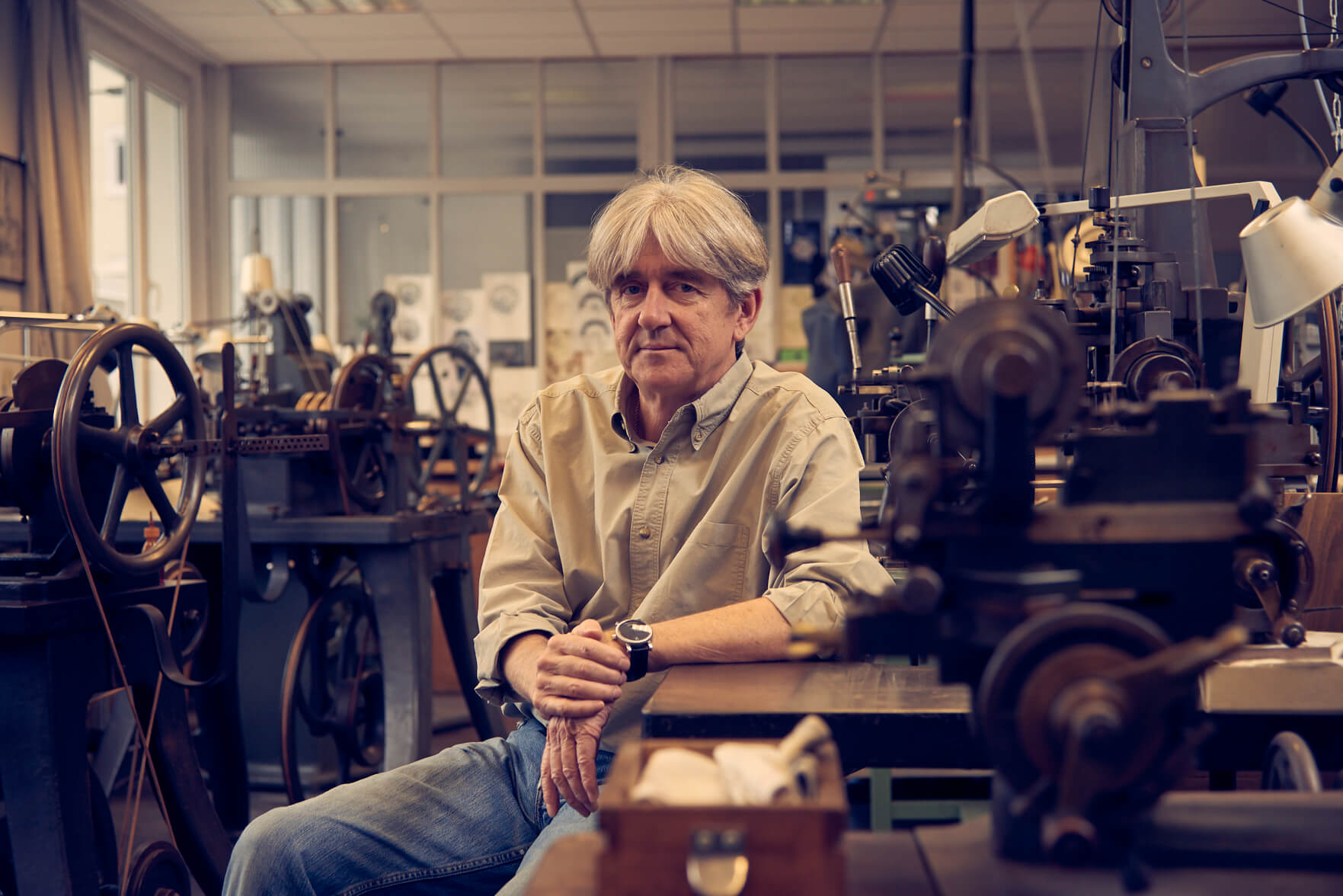

Jochen Benzinger in his Pforzheim workshop

Guilloché down under

Australian watchmaker Oliver Broos Revitt is enamored by traditional guilloché, so much so that he bought his own straight line engine.

“There was no plan to originally get it (the straight-line engine),” Revitt says. Since seeing guilloché machines at German watchmaker Jochen Benzinger’s workshop in Pforzheim, Revitt has changed his mind. “I spoke to Jochen and said, ‘hey mate, I wanna come over and learn (guilloché).’ He gave me three days and I said, ‘why not a week?’ He said, ‘trust me, your thumb’s gonna be so sore after three days, that’s what most people can handle.’ He was right.” During his time working with Benzinger, Revitt discovered two guilloché machines for sale. “How often do you get the opportunity to buy one of these?” Revitt says. Revitt takes the opportunity to buy a straight-line engine. “The second time I saw him (Benzinger) I stayed there for a bit over a week, and he showed me some more stuff…and then I packed the machine up and brought it back (to Australia)”.

Revitt has used his guilloché machine to make small accessories such as money clips and cufflinks. His long-term aim, however, is to create his own watch dial.

Tools of the trade

Revitt’s straight-line engine is made by Neuweiler und Engelsberger. A guilloché machine manufacturer who was operating from Niefern, Germany, just eight kilometers from Pforzheim. Other major guilloché machine manufacturers include Lienhard SA from Switzerland and G Plant & Sons in England. From 1760 to 1920 (the main period of guilloché machine manufacture), less than 8,000 machines were made. New machines are rare, especially for sale to the public. Patek Philippe manufactures their own machines for the guilloché on their watch dials. David Lindow is a watchmaker based in Pennsylvania in the US and remains one of the few makers of commercially available rose engines. Lindow and his partners make their machines under the brand name MADE and have been working on improvements to traditional rose engines since 2010.

Nothing beats the real deal

While many mid-tier watch brands use CNC machines to mimic these patterns, there are a small number of heritage brands still practicing the art as they have done for centuries. This includes industry giants, such as Breguet, Vacheron Constantin, and Patek Philippe. There are also newer brands and individuals who have made their name creating traditional guilloché dials such as RGM from the US and Roger Smith in the Isle of Man. These makers’ dedication to traditional arts is appreciated by their buyers. “You can still tell when a dial has been hand-guillochéd,” Revitt says.

Revitt is optimistic about the future of guilloché. “Sure, demand isn’t as high as what it was in the past, and people are using CNC, but someone is always going to want guilloché.”

What are your thoughts on the results of this undeniably masterful craft? Would you be willing to shell out the big bucks for a hand-engraved guilloché dial? Or is it the kind of thing you’d rather steer clear of? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below!