In-Depth: Horage Lensman 2 Exposure — A Watch With A Photographic Cheat Sheet

Founded in 2007 and with the presentation of its first watch in 2009, Horage is not exactly new to the watch scene anymore. We’ve seen many brands (specifically those of the “micro” variety) enter the stage after that. Although not a big brand regarding production numbers, I wouldn’t describe Horage as a microbrand. There’s too much in-house development and production going on, and the solutions and products presented are too complex to suit a microbrand.

Now, before this article shifts towards discussing how and when a brand is considered a microbrand, I’d like to refer to our “Definition Of A Microbrand” article. With that out of the way, let’s get to discussing the newly introduced Horage Lensman 2 Exposure and its unique functionality.

Horage Lensman 2 Exposure

While my colleague Ben did an excellent introductory article on the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure last month, let me dive deeper into its unique functionality — a photographic exposure calculator. The word “photography” comes from the Greek words photo (light) and graph (to draw). Modern-day photography is the outcome of many technological developments, most notably associated with the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century but also by optical devices used during the Renaissance to aid drawing and perspective. Photography today means capturing an image on light-sensitive film or, primarily, on a digital electronic sensor.

Before one can understand the exposure cheat sheet that the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure offers, it’s essential to understand the basics of photography. So let me start with that before explaining the use of the Horage’s unique function.

The basics of photography — three ways to influence the amount of light

Whatever way is used to produce a picture, light is the essential ingredient to achieve a good result. Without light, there is no photographic picture. The second-most important factor is the amount of light needed to make a technically acceptable picture. This amount of light, captured on light-sensitive film or a digital electronic sensor, can be influenced in three ways in photography. In practice, the film or sensor is exposed to outside light by opening a lens for a specific time. The three ways of influencing the amount of light that reaches the film or sensor are (1) the opening of the lens and distance to the film or sensor, (2) the time the lens is opened, and (3) how sensitive the film or sensor is to picking up the light.

Aperture

The distance of the lens to the film or sensor is known as the focal length. Divided by the lens’s opening diameter, it gives the aperture value. So, the aperture is indicated as a unitless value and shows the relationship between the diameter of the lens and the focal length. An aperture of 4 means, for instance, that the opening diameter of a lens with a focal length of 100mm is 25mm. Equally, a lens opening diameter of 10mm gives an aperture value of 4 on a lens with a focal length of 40mm. The same amount of light will reach the film or sensor in both cases.

Aperture values exist as a range of so-called “full-stop” numbers. Examples of these full stops include 1.4, 2, 2.8, 4, 5.6, 8, 11, 16, and 22. An important thing to know is that every next aperture step, or stop, halves the amount of light reaching the film or sensor. An aperture of 8 lets through half the light compared to an aperture of 5.6.

Shutter speed

An easier thing to understand is the influence of the time that a lens will be opened. The opening time is indicated in seconds and fractions thereof. Examples are 1/1 second for a very long opening time to 1/8000 of a second for a very short time. These times, or shutter speeds, also have full-stop values and are pretty easy to understand. Like every aperture stop, consecutive shutter-speed stops also halve the amount of light reaching the film or sensor. For example, 1/60th of a second transmits half as much light as 1/30.

ISO

The third and last element of the so-called “exposure triangle” is the ISO value. In photography, ISO is the standardized industry scale for measuring sensitivity to light. Initially, it referred to how sensitive film was to light, and now it also relates to a camera’s digital sensor’s sensitivity to light. A lower ISO number means your film or sensor will not absorb as much light as a higher number.

Again, here we also have stops — 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, and so on. ISO 100 means that your film or sensor only needs half the amount of light to produce a correctly exposed image, as would be the case with ISO 50. ISO values may go up as high as 12,800. So why not always use these high ISO? Technically, it would go too far to explain this, but the result of using high ISO values is increased noise in a picture. And not only that, but it also reduces the dynamic range and color accuracy of a photograph.

Lighting condition example

Let me give some examples to enhance the understanding of the above. Assume we use the following values to take a properly exposed photo of a subject outside on a cloudy day: ISO 100, – f/5.6 – 1/250 s. And next, in the same situation, we’re going to use ISO 400 instead of 100 (two stops up). We could increase our shutter speed to 1/1000 (two stops down). Or — not and — we could use the smaller aperture (higher number) of 11, which would also mean two stops down. Alternatively, we could increase our shutter speed by one stop to 1/500 and increase the aperture value by one stop to 8. All three settings would produce an identically exposed photo.

Let’s hurry back to the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure

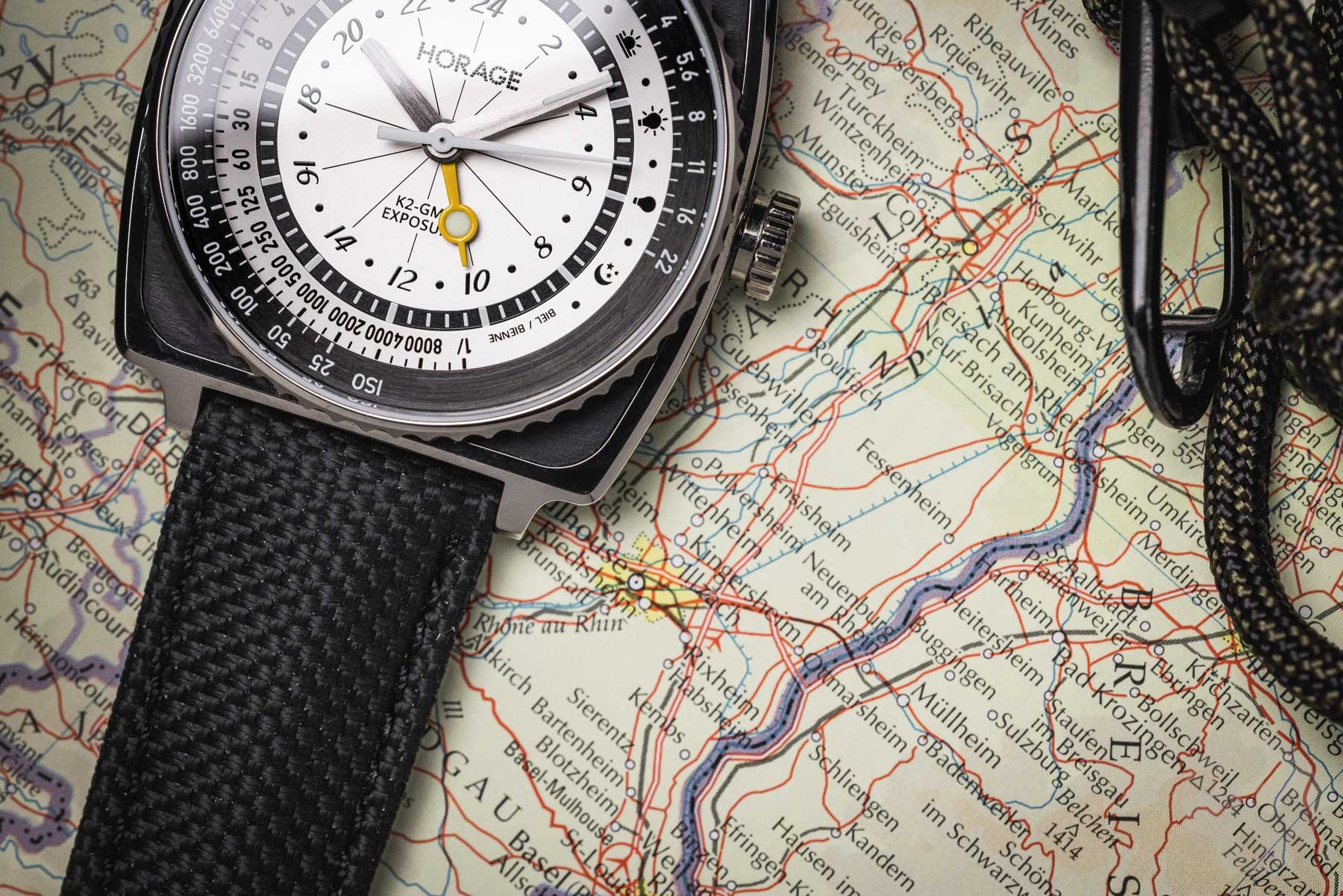

I agree, this theoretical stuff has taken way too long; we’re here for the watch. But I had to get this out of the way before being able to explain the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure’s unique function. But first, let me start by loosely quoting my colleague Ben on the execution of the watch before heading to the operation of its specific functionality. The Horage Lensman 2 Exposure resembles past-era camera gear with its bimetallic exoskeleton case. The dual-material case comprises a polished Grade 5 titanium outer square with a black anodized aluminum inner portion. The diameter measures 39mm, and the impressive K2 GMT movement is visible through the back, with the micro-rotor made of tungsten for the standard models and platinum for the Brian Griffin limited edition.

Photographic cheat sheet

Let’s get to the point now and see how this new and unique photographic cheat sheet feature of the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure works in real life. It’s at sunset, and you have your camera filled with an ISO 100 film. Or, for digital photographers, you want to make your picture on the ISO 100 sensitivity of your sensor.

On the Lensman 2 bezel, you’ll align ISO 100 (green arrow) with the sunset image (red circle). Then there are two options. You either chose a specific aperture (for depth-of-field reasons) or a shutter speed (because of the speed at which your subject is moving). Let’s assume neither is very important; the subject is static, and you just don’t want camera motion blur, so choose a shutter speed of 1/125 sec. (orange arrow). Looking at the Lensman 2 bezel (adjusted to ISO 100 at sunset), you’ll learn that you have to adjust your lens to an aperture of f/4 (blue arrow). It’s as easy as that. It was at sunset, and as benefits a good journalist, I checked the outcome with my Kenko KFM-1100 digital light meter, which, unsurprisingly, gave the same results.

Film photography

The above example would be specifically valid for film photography; for digital photography, not so much. Taking or making photographs on film means that your camera is filled with one specific sensitivity of film; ISO 100 in the example above. That’s where you’re stuck, unable to change the sensitivity from picture to picture. You can only do that from film roll to film roll.

How is this different from digital photography? Here, the ISO value — the sensor’s sensitivity to light — is as adjustable as the shutter speed and lens aperture. In digital photography, any of the three variables — ISO, speed, and aperture — can be changed for each subsequent picture. Besides this, every digital camera has a capable light meter, making the Lensman 2’s function somewhat obsolete. Even vintage film photo cameras have light meters on board, although most are not reliable or functional at all anymore nowadays. So that’s where the specific function of the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure comes in handy — film photography with vintage cameras.

Personal observations

I was lucky to test and try the Lensman 2 Exposure Brian Griffin LE for a week. What did I notice? First of all, the weight. It was much lighter than I expected from the pictures I’d seen. But, probably because I wasn’t paying close enough attention, I didn’t realize the watch was made of titanium and aluminum. Both are incredibly light metals. I can’t say this counts as an advantage for me. I’m happy to feel a substantial watch on my wrist when there is one.

Second, I noticed that rotating the bezel is quite difficult. I understand unintentional bezel rotation isn’t desirable, but it’s almost cumbersome here. And as far as I’m concerned, there’s no reason for that. There’s no life-threatening situation if the bezel rotates unintentionally. The bezel is only there to learn the values of how to set your camera for the following picture.

Third, I do not like any folding buckle, and the one on the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure is no exception. It might be Swiss made (although it doesn’t say it is), but it’s not my thing. I also believe it’s not on par for a roughly €6,000 watch. I’d prefer a solid, nicely shaped, and engraved pin buckle.

Fourth, why is that distracting 24-hour hand there at all? Why would you want that on a watch with this specific functionality? The dial is cluttered enough; there’s no need for a 24-hour scale and hand to make it even worse. I don’t understand Horage’s website text either: “The GMT hand has a sizable aperture filled with white X1 Super-LumiNova®.” Aperture is a peculiar word to use for the lumed section of this hand. While technically not incorrect, it is a little confusing, given the context of the watch.

My fifth and last observation is a positive one that blows away the above critical ones. The Horage K2 micro-rotor caliber is extremely beautiful! I could wear the watch upside down. The different finishes, structures, and colors/materials are unbelievable. Chapeau!

Conclusion

First and foremost, the Horage Lensman 2 Exposure is a stunning watch, and the Brian Griffin LE is definitely my favorite. Specifically, its construction and the use of materials are groundbreaking, not to mention the level of finishing for both the casing and movement. From the first moment you have the watch in your hands, it’s evident that this is something special. Plus, Horage didn’t praise the one-of-a-kind photographic exposure feature too much. It’s perfectly functional, and, just as necessary, it submits the right results.

Perhaps the only thing is that the target audience for this feature is somewhat limited. It’s really only useful for photographers using vintage film cameras without a light meter. I can’t think of any other practical use for it, at least. I would be happy to learn from your comments if you think otherwise. Nevertheless, it is only to be applauded that Horage has managed to add a feature that has not been seen before.