In-Depth: Researching The Vintage Movado Museum Watch

Sometimes, an item can become so ubiquitous that we fail to question its history. Such is the story of the Movado Museum Watch. Sure, there’s a commonly told story, but for an item that even horology neophytes recognize, the history is brief and lacking. What started as a typical fact-finding mission turned into an ongoing search for more.

You’re instantly forgiven for uttering the words “Who cares?” after reading “Movado Museum Watch.” After all, the once-pure design has been raped, pillaged, and left for dead in every way imaginable over the past 60 years. The idea of a simple watch that evoked a sundial with the Sun at high noon started and ultimately became the face (pun intended) of the current Movado brand. Today, we’ll look at the history, attempt to debunk the commonly recounted stories, and view the vintage references. Finally, we’ll go hands-on with one of the vintage models.

Why the Museum Watch?

As a child of the ’80s, I was used to seeing the Movado Museum Watch everywhere. It was incredibly popular in the USA, and the design worked well for slim, two-tone quartz pieces on bracelets and straps. I suppose it’s a credit to the original 1947 design that it translated so many years later (not to my liking, but that’s beside the point) and found repeat success. The success was so great that Movado had standalone stores in high-end malls during the ’90s. The brand sold jewelry and accessories using the Museum Watch as the underlying design inspiration. As a youngster during that period, I found Movado artsy and modern, but it wasn’t really my thing.

Fast-forward a decade (2003, I believe), and I was in a Toronto jewelry store in Queen’s Quay. I recall a new-old-stock Museum Watch made in 1994 to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Bauhaus movement. It was lovely with a gold-plated case and hand-winding movement, but at $450, I decided to pass. Still, the watch stuck with me, and I vowed to find an original vintage model. I finally found an example on eBay in June 2024, and since then, I’ve been struck by two distinct observations. First, I love this watch and find it highly underrated. Second, for a watch that probably ranks as one of the most recognizable designs of all time, there’s surprisingly little historical information.

The beginning

A casual search on the Movado Museum Watch and its history leads to the designer Nathan George Horwitt. Horwitt was born in Russia in 1898 and was based in New York City and Massachusetts for most of his working life. After working several jobs, he became a noted industrial designer. Horwitt created many objects, including furniture, clocks, and even a frameless picture frame. All told, he amassed 18 US patents before passing away in 1990.

In 1947, Horwitt created his magnum opus, although it would take a surprisingly long time for the rest of the world to take notice. Horwitt envisioned a watch with a black enamel dial and an applied round gold disc at 12 o’clock. A sundial was said to be the inspiration, and he wanted observers to take note of the changing relationship between the two simple stick hands and the dial. He produced three prototypes using off-the-shelf 14K white gold Vacheron & Constantin watches with stick lugs and manual-wind LeCoultre movements. Thus far, I have not found any information on where the dials were produced.

The whereabouts of two of the prototypes are known. One was accepted in 1960 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City as a gift from the artist. It carries a creation date of 1947. Horwitt also gifted the second prototype to the Brooklyn Museum in New York in 1985. It carries a creation date of 1955. Horwitt kept the third prototype, and the whereabouts are not publicly known.

Not overly successful in the beginning

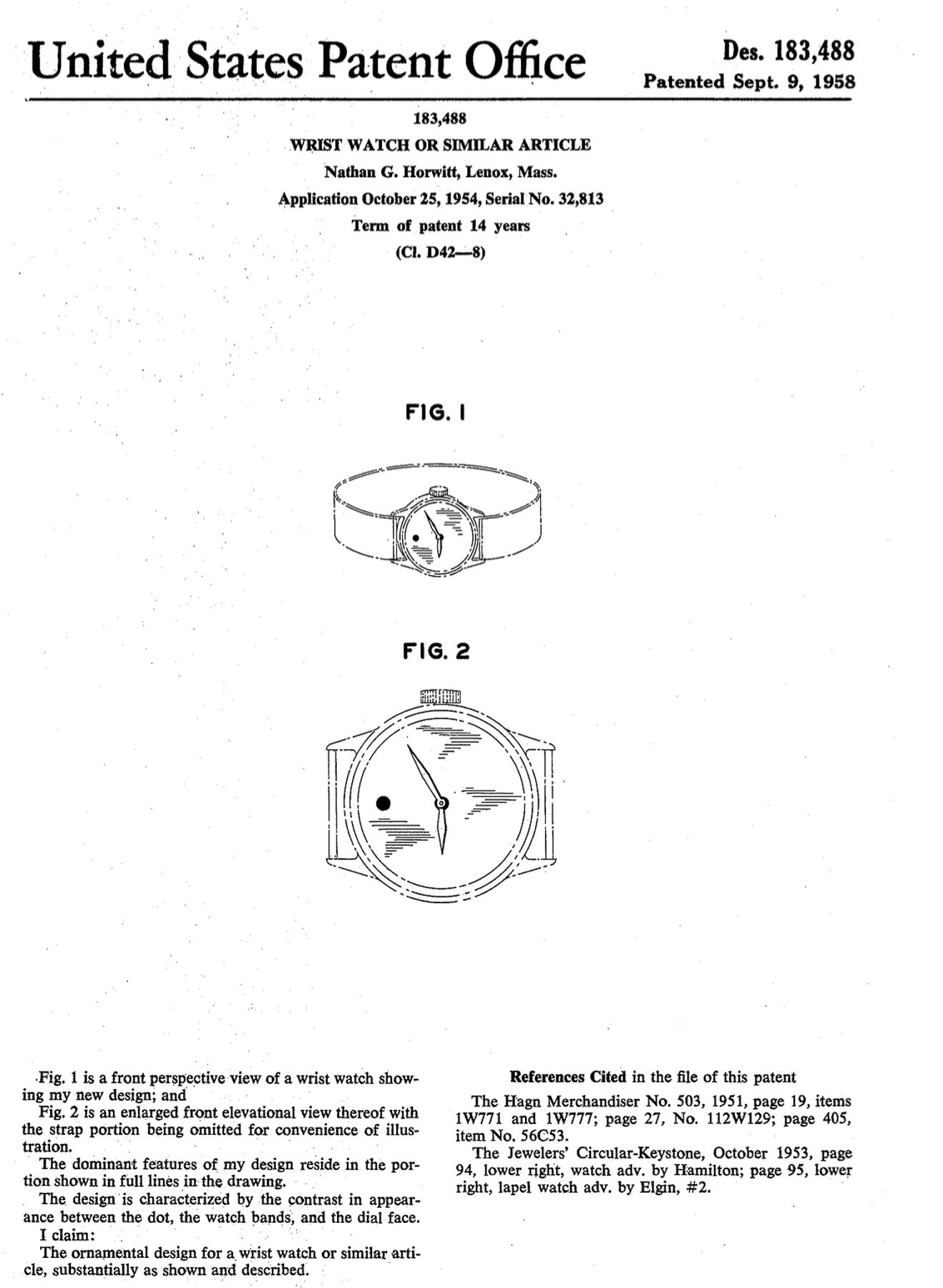

The original Museum Watch design first came to light in 1947, but there were no initial takers. Fritz von Osterhausen, in his book The Movado History, reports that Horwitt failed to convince Vacheron to produce the watch during that year on a trip to Geneva. Accounts opine that the design was seen as too futuristic and sparse for the period. The story then goes quiet for a lengthy period, with reports that further prototypes were made, including a smaller piece for women. Intriguingly, Horwitt filed for and received a design patent in September 1958 after an initial rejection in 1956. From the photo above, it’s interesting how simple the description is and that he was able to protect such a rudimentary design. Also, note the patent’s 14-year length, which will be a pertinent fact later in our story.

A very brief glimmer in 1960

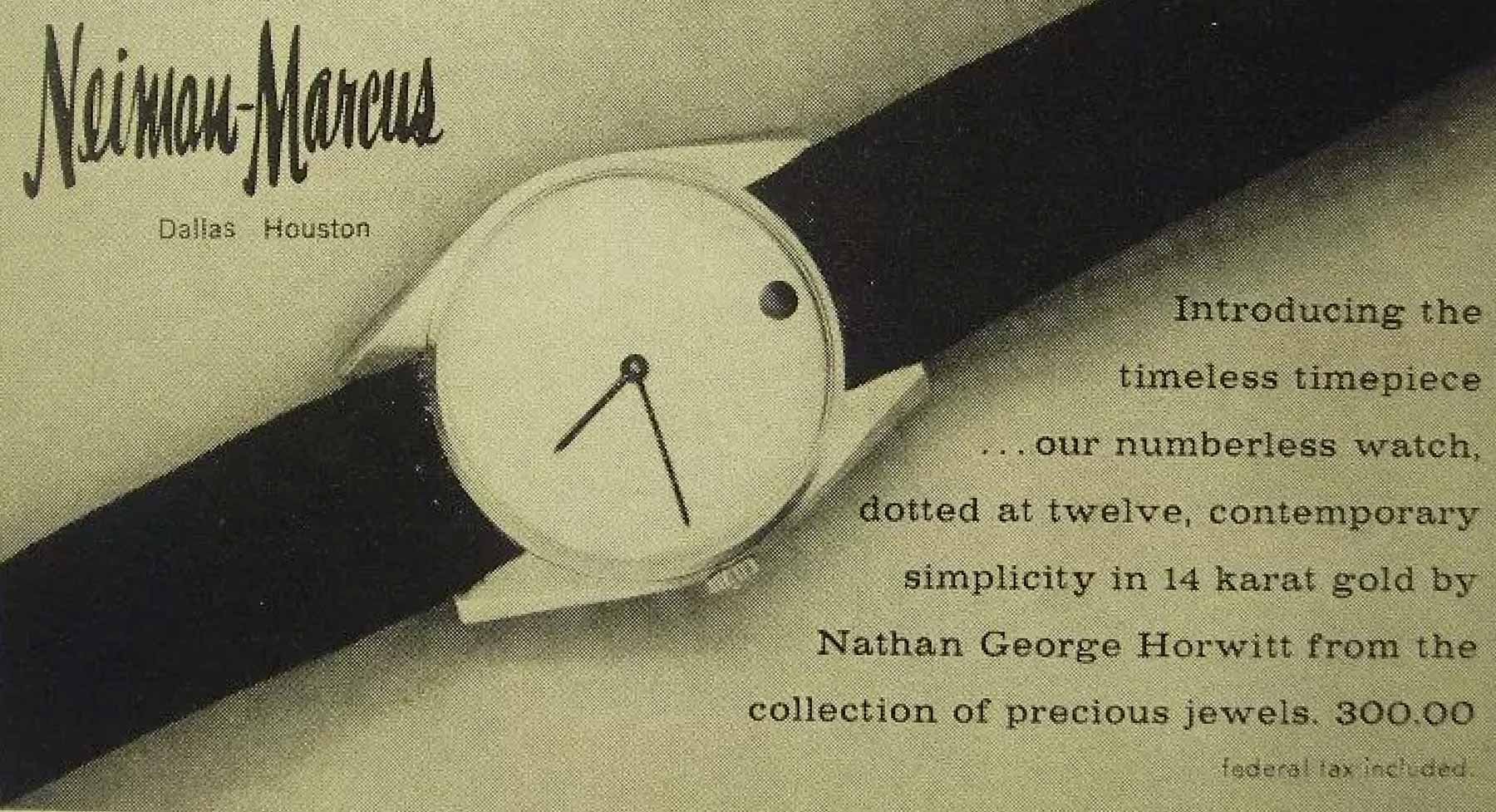

In 1960, the luxury American department store Neiman-Marcus offered the first commercial version of Horwitt’s creation in its famed Christmas catalog. The pixelated image makes it difficult to examine. However, a newspaper article from Horwitt’s hometown states that the watches were produced by a major manufacturer and had white dials, a black dot, and black hands. The ad indicates that the cases were 14K gold, but it could be white or yellow. Finally, it appears that the crown has an engraving. To my knowledge, none of these early pieces has ever surfaced, so there are still questions.

Movado signed on in 1962

In 1962, the Museum Watch became interesting enough to garner interest from a major brand. This is our first opportunity to debunk the most commonly told myth about these watches. Changing tastes and possible interest in the watch on display at the MoMA may have led Movado USA to take a chance and produce the watch. It’s important to note that this is where many historical accounts state that Movado “stole” the design and began profiting from its sales. My research shows this to be untrue.

Myth 1: Movado “stole” the Museum Watch design

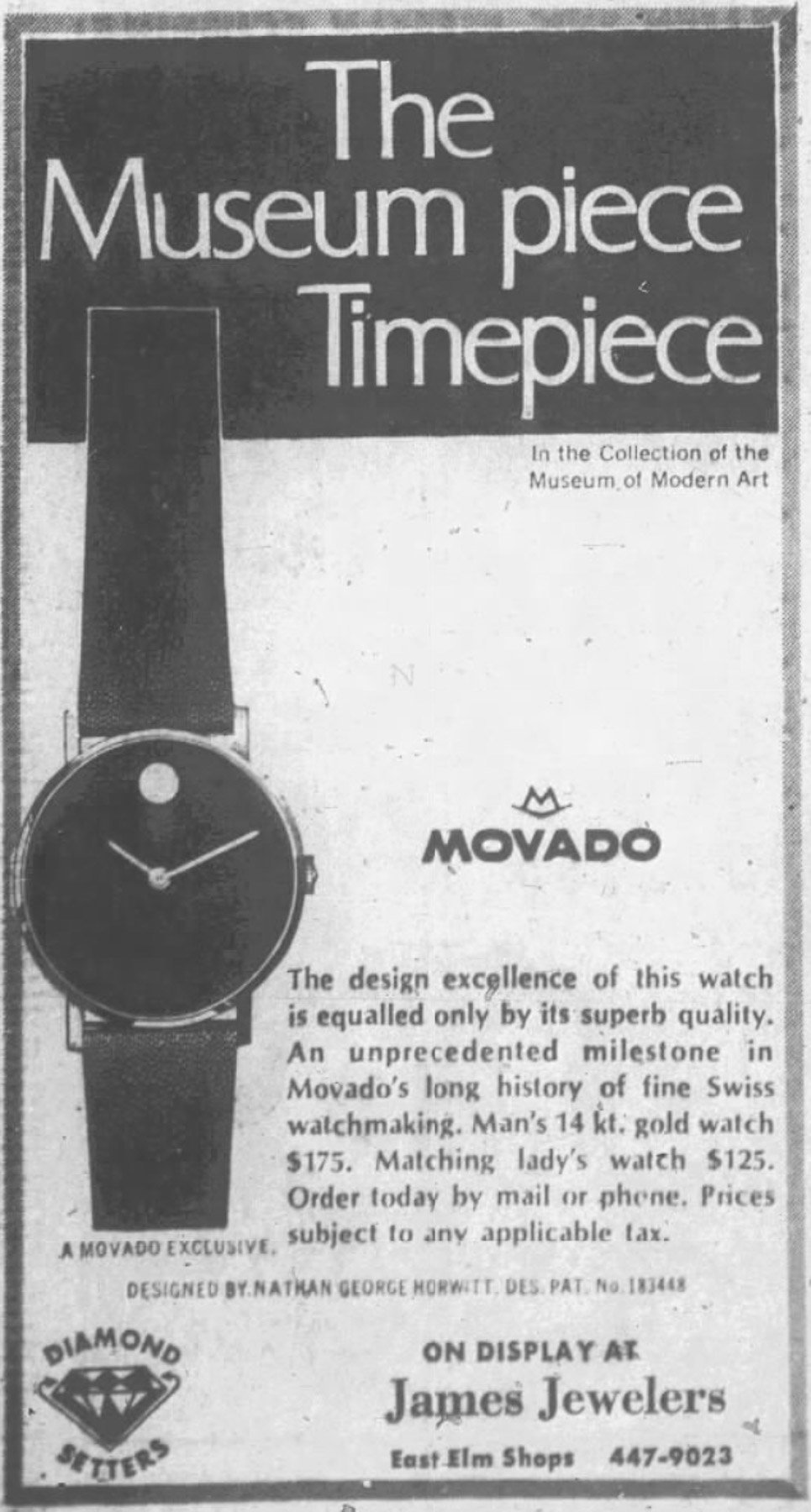

A 1975 case, Horwitt v. Longines Wittnauer Watch Co., Inc., refers to a royalty agreement that Horwitt had with Movado Watch Agency Inc. from 1962 through 1971. Remember, the design patent expired in 1972. During this timeframe, Horwitt received 10% of all sales until June 1969 and 7% thereafter. The total was approximately $45,000, and the watch showed increasing popularity toward the decade’s end, which led to higher royalty payments despite the reduced percentage. See the 1968 advertisement above, which mentions Horwitt’s name and his design patent.

This doesn’t mean that Horwitt wasn’t frustrated after the patent expired. I found an article in his hometown newspaper in which he expressed that he had earned roughly $65,000 in total from the watch while Movado continued to make millions. Per the court case above and several others, Horwitt was an adamant defender of his design patent while it was valid. He settled with companies, including Hamilton, due to patent infringement while unsuccessfully challenging other brands.

Interestingly, Movado countersued Horwitt at some point after 1972 for the return of royalties as the company challenged the originality of his design and, therefore, the patent. I’ve been unable to find the 1940s Omega and Girard-Perregaux watches that, according to Movado, had similar dials. While I have no idea of the exact arrangements made between Horwitt and Movado during his lifetime or after his death, his name and image are used on the brand’s website.

Myth 2: Movado produced the watch in the ’40s and ’50s

To debunk another myth, and this now sounds obvious, Movado did not produce this watch in the ’40s or ’50s. Most sales ads for a vintage Museum Watch refer to these decades as the presumed production period. The supposition makes sense to a degree because it now seems mind-boggling that this all-important design sat idle for the better part of 15 years after Horwitt first designed it. It also doesn’t help that Movado does not provide any extract information on its watches.

The earliest Movado Museum Watches are a mystery

Most historical accounts state that Movado produced the Museum Watch as a US-only model for the first several years after 1962. The watches used US-made cases and dials with Swiss movements. In his book, von Osterhausen claims that the watch later entered Swiss production in 1965 and was equipped with the manual-wind Movado calibers 245 or 246 based on the Universal Genève calibers 820 and 42, respectively. This leaves us with a mystery.

Visiting the revived Ranfft site tells us that the Movado caliber 245 was introduced in 1960 and the 246 in 1965. If we take these introduction dates as gospel, what movements did the earliest Museum Watches use? One would presume a 245, but I’ve never seen a 245-powered Museum Watch or any movement other than a 246 in an early Museum Watch. Also, as we will see, my watch is a 246-powered piece and features a US-made case. So, where does this leave us? If I had to guess, the caliber 246 debuted earlier than 1965 and was used from the beginning.

Searching for vintage specimens

For something as recognizable as the Museum Watch, most would assume that the market is inundated with early examples. Several days of clawing through the internet tells me this is simply not the case. If we recall that Horwitt saw an acceleration in royalties toward the end of the patent period, this is a hint that the watch wasn’t as popular at the beginning of production. Of course, many watches have likely been lost to damage, scrapped for gold, or have not resurfaced. My research for larger (>30mm) vintage examples with domed acrylic crystals has revealed approximately 20 watches. Do note that 24mm pieces were marketed to ladies.

Allow me to clarify further. First, I’m 100% convinced there are significantly more watches remaining. Perhaps they have not been labeled well for easy searching. Second, I have limited my research to earlier manual-wind models without “Zenith” on the dial. If you own a later Movado Zenith Museum Watch, please don’t take any offense, but I prefer the simple early models without date complications, flat crystals, etc.

The movements and watches

In my research, I have found two movements used in the earliest Museum Watch models. Many models I located did not contain specific movement information, so I made assumptions based on case design and engravings. Also, it’s good to understand how Movado numbered its watches during this period. The reference numbers contain three sets of three digits separated by dashes, such as 246-224-085. Some watches contain an additional four-, five-, six-, or seven-digit serial number below the reference number on the case back, while others have the serial number on the case. If you have any additional information, photographs, or references regarding all of these watches, I welcome your contributions.

The first set of three digits denotes the caliber. For this article, it includes the 246 and 352. The second set of three digits must be cross-referenced to a table in von Osterhausen’s book. It reveals two pieces of information. The first two digits in this block relate to the case material, while the third digit refers to the shape of the watch and/or the type of strap or bracelet. For all of the early Museum Watches, this third digit in the second block is “4,” meaning the watches are round. Finally, the last set of three digits denotes the type of crystal. Any number within the range of 001 to 299 cross-references to an acrylic crystal.

The 246-powered models

As mentioned, the Movado 246 is a manual-wind movement based on the Universal Genève caliber 42. It measures 19.8mm in diameter by 2.45mm thick. Specs-wise, the 246 has a frequency of 21,600vph, a power reserve of 52 hours, and 17 jewels. This movement was supposedly produced from 1965 until 1971. The Museum Watches that housed it have a 32.5mm case diameter with 18mm lug spacing. Note that these models show differing case styles. The Swiss-made cases have strongly angled tip lugs and a different side profile, whereas the USA-made cases are more basic with flatter-tipped lugs. However, there are also differences between precious metal and steel cases.

Reference 246-214-027

Reference 246-214-027 denotes an 18K white or yellow gold watch, and my assumption due to the alloy type is that these were Swiss-made cases. I have located one example in white gold sold at Antiquorum in 2021. In this example, the lugs are angled and pointed at the tips. Also, the lugs are attached to the case below the bezel’s top edge.

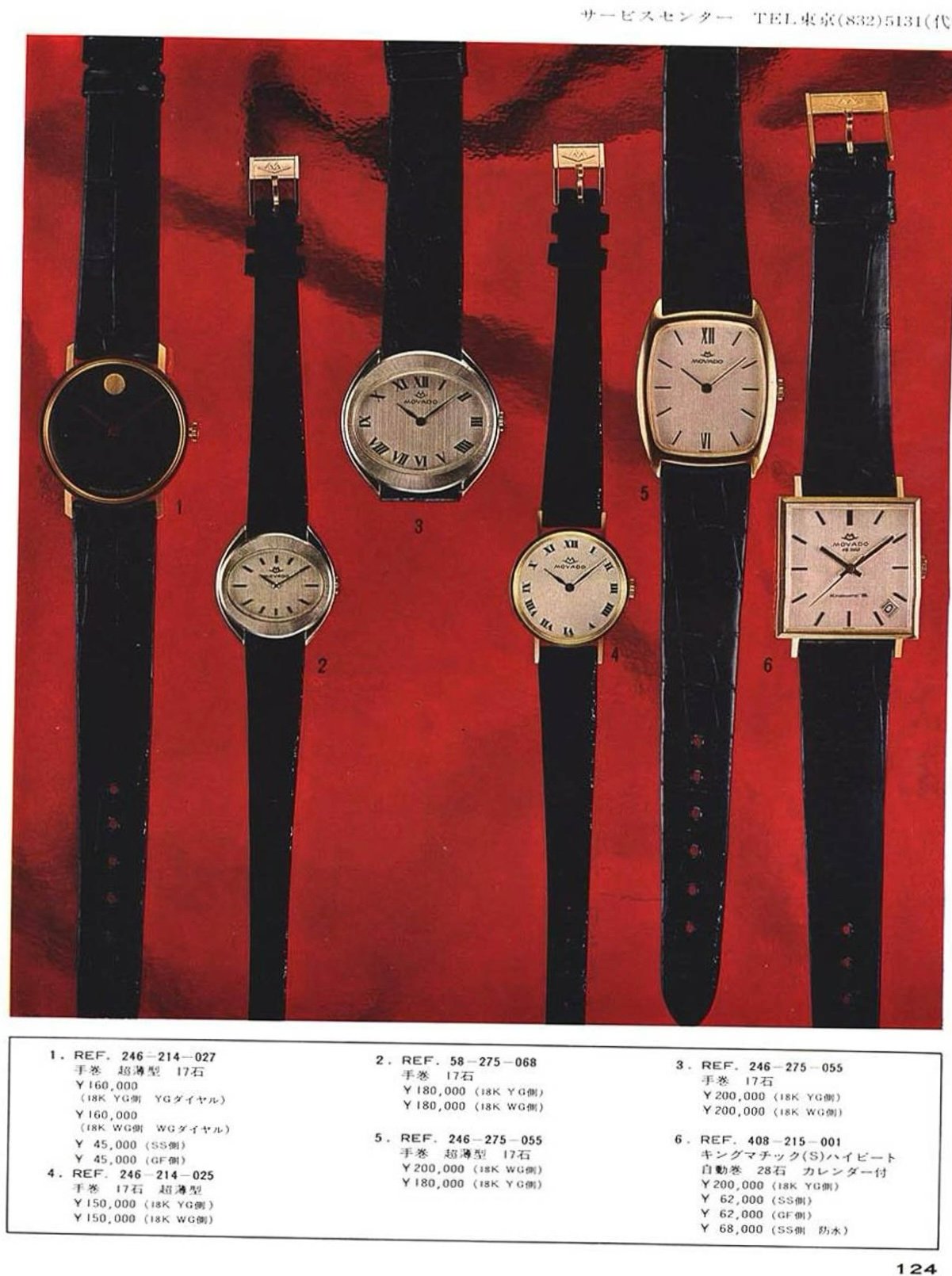

I have not located a yellow gold specimen, but there is an image from a Japanese catalog. The site owner claims the image is from 1970, but I believe it is earlier as the watches would have likely been advertised with Zenith markings on the dial by this time. In this image, we can also see the correct buckle for these models, which bears the so-called “Fedora” logo.

Reference 246-224-085

Reference 246-224-085 is a 14K yellow gold Museum Watch. Examples of this reference were the most common ones I found online, and all but one were in the USA. Similarly, every listing that contained a photo of the underside of the watch’s case back showed a stamp indicating USA production. The watch above is from a WatchUSeek forum post in which the owner states it has been in his family since it was new.

I also found a lone example with the same reference number and case material but on a mesh bracelet. This specimen was sold at Antiquorum in New York in 2009. Also, and perhaps this supports the claim that the 246-224-085 references were the earliest production models, this reference number can be found on watches with similar cases but without Museum dials.

Reference 246-624-027

Reference 246-624-027 denotes a case with 20 microns of yellow gold plating and a stainless steel case back. As we can see, this is a Swiss-made case, and it differs from the 14K gold model in construction. Still, all of the examples I have found are in the USA.

Reference 246-704-027

Reference 246-704-027 is intriguing because it’s a fully stainless steel model. I discovered this example after punching in some different number combinations that might make sense. This beauty recently sold on Yahoo! Japan Auctions, and I’m sad to have missed it! The watch features a Swiss-made case with the same lug profile and case back as the gold-plated version. Unlike the 14K gold 246-powered models, the steel model has its serial number inscribed on the back of the case.

Caliber 352 — Image: @the.vintage.collector

The 352-powered models

The Movado 352 is a manual-wind movement also based on a non-Movado caliber. In this case, the Zenith 1730 was the basis. This movement is 17.5mm wide by 2.7mm thick and has a frequency of 21,600vph. The power reserve is 38 hours, and the movement contains 19 jewels. Von Osterhausen states that this was a USA-only movement, and Ranfft shows a production period from 1967 to 1969. Based on sales ads, I believe that the USA cases were 32.5mm in diameter and identical to the USA-made 246 cases. The Swiss-made cases appear to be smaller at 30.5mm wide with a 15.3mm lug spacing. I hypothesize that the 352-powered models came after the 246s due to the 1968 merger of Zenith and Movado. However, I would not rule out the possibility of both models being sold simultaneously in the same or different regions.

Reference 352-214-027

The reference 352-214-027 is an 18K yellow gold model on a mesh bracelet. I assume there are versions on a strap, but I have not located an example yet. This piece was sold in Hong Kong at Antiquorum in 2016, and the description lists a 30mm diameter. If we compare the bracelet quality to the 246-powered model on mesh, this appears much finer. Unfortunately, the dial is misaligned!

Reference 352-224-085

As with the 246-powered models, Movado offered 14K and 18K to meet different market preferences. The 352-224-085 denotes a 14K yellow gold case. I have located one model on a strap with a US-made case. Incidentally, the case design is identical to the 14K yellow gold case for the larger caliber 246, and this watch’s owner states that it has a 32.5mm diameter. Even the inscriptions on the underside of the case back are of the same style.

Reference 352-284-085

Another lovely reference is the 352-284-085 Museum Watch with a white gold case. Like the yellow gold model, this also uses a USA-made case but has seven digits in the serial number instead of five. Interestingly, the movement picture allows us to see how the famous dot is affixed to the dial. The owner of this stunner asked questions about it on the forum WatchFreeks back in 2011. It’s a fun little post to read and full of questionable advice! Sadly, I’ve never seen another one of these, but it would be a lovely model to own.

Reference 352-624-027

Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to locate a specimen of reference 352-624-027. The Japanese catalog image lists it as “GF” (gold-filled). However, because of the “624” nomenclature, I believe the watch pictured has 20 microns of yellow gold plating. Additionally, the lug ends are more severely angled, which leads me to believe that this watch has a 30.5mm Swiss-made case. Interestingly, the catalog mentions a stainless steel version with the same reference number, but that was most likely the following watch.

Reference 352-704-027

The final reference is 352-704-027, a stainless steel model. I have located four of these references and believe all are 30.5mm in diameter with Swiss-made cases. Another striking characteristic of these references is the highly patinated brownish dial. There is no reason to believe these were anything but black in the ’60s, but all have turned this lovely shade for whatever reason. There’s no radioactive lume, so the reason is a mystery!

A hands-on review of a vintage Movado Museum Watch

There’s a core group of us keeping watch over all things Movado on the usual auction sites. On eBay, the platform is overrun with modern Museum models, making it rare to find something interesting. Back in June, though, I stumbled across a 14K yellow gold reference 246-224-085 Museum Watch with a USA-made case, and luckily, it was here in the UK. The watch looked okay but probably needed a new crystal. With a buy-it-now price of £400, I deliberated for a few days before hitting the button.

The watch arrived a few days later, and honestly, it was one of the more highly anticipated packages for me. I had never seen a vintage Museum Watch in person, but I recalled the bubbly domed acrylic crystal on the 1994 reissue and how it added warmth to the relatively cold, sparse dial design. In fact, the acrylic crystal is a key reason I don’t love later models with flat sapphire crystals. Needless to say, the vintage version exudes the same feeling of warmth.

Bigger than its 32.5mm size suggests

It’s also important to note that despite the smallish 32.5mm by 38mm dimensions, the Museum Watch doesn’t feel especially small. Even with the dark dial (we know, dark clothes make us look thinner), the flat, thin bezel and stick lugs work harmoniously and visually stretch the size. Speaking of the lugs, they’re simple and angled down to hug the wrist. It also helps that the watch seems unpolished.

Inspecting the condition and fixing the crystal

The dial, however, is not flawless. I wound the 246 and wore the watch for a few hours around the house with a sense of pleasure. Then, when I removed my contact lenses in the evening and went in for a closer look, I noticed that the dial contained some signs of diagonal wiping across the lower portion. I opened the case and popped the movement and dial from the case back’s cradle. Sure enough, I found signs that something had interacted with the black enamel. I used some swabs with water to no avail, but under the crystal, it’s not overly noticeable. Thankfully, the gold “Movado Swiss” along the bottom is still there, although it is light.

I noticed the likely culprit that led to dial intrusion. The crystal was no longer attached to the case on the lower-left side, so the watch went away for several weeks until I met my buddy Lawrence in London to arrange an express fix in the city. Just £60 later, my watch was sorted.

Owning a piece of art

Here’s what I will say about finally owning a vintage Movado Museum Watch. This is one that collectors shouldn’t dismiss so readily, even if the modern models have watered down the design to the extent that it has become kitschy. These early references feel like pieces of art. The simple cases and aged enamel dials look like something that has been in a museum for decades, yet the design is still somehow quite modern and relevant.

The right strap is key

When the watch arrived, it came on a plain black leather strap that looked pretty good. It was a cheaply made one, though, and I was wondering what to pair the watch with instead. I went to my bag of unloved straps (every collector has one) that were unworn and likely came with some vintage purchases. We keep these straps despite knowing there’s a slim chance of ever using them. But then, eureka! I found a NOS 18mm black JB Champion strap that works perfectly with the watch. I rarely choose these types of straps, but I cannot think of anything better!

Values and availability

Regarding values for any of the Museum Watch references I shared above, they’re all over the map. People barely seem to care about them. Their smaller size and relationship to the hackneyed modern models haven’t helped. As a result, I fear that many have been scrapped or are rotting away in a drawer because people think they’re worthless.

A $200–2,000 budget should net any vintage Movado Museum Watch, which means that almost all interested collectors can play as long as they can find them. In my view, you’re getting a genuine art piece with a fascinating history. Plus, as an American, I can’t help but beam with pride that it’s a rare case of American industrial art that has gained global popularity. The normal rules for vintage watches apply when buying a Museum Watch, but movement parts are available, and the dials are so simple that they’re rarely touched.

Final thoughts and conclusions

The Movado Museum Watch may not resonate with everyone, and that’s fine. Still, there’s no disputing that it’s one of the most recognizable watch designs from the past 60 years. Therefore, I was surprised to find a paucity of information and kept reading the same (mostly incorrect) two or three paragraphs on multiple sites. Researching a watch like this takes time, and it gave me a newfound appreciation for those who do it regularly. Thankfully, we are in the digital age, and newspaper archives exist. I hope you enjoyed this in-depth look at a trailblazing design, and maybe you’ll think differently about the Museum Watch in the future.

I’d like to thank those who contributed to this story or helped me along the way. Charlie Dunne, Eric Wind, @mostlymovado, and @the.vintage.collector all provided information, images, or clues on where to find more history. Thank you!