There Is Nothing Left To Reintroduce, Or Is There? What About The IWC Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar IW3750 From 1985?

The IWC Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar IW3750 from 1985 is an important watch for IWC and the entire Haute Horlogerie universe post-Quartz Crisis. Master watchmaker Kurt Klaus built a perpetual calendar mechanism on top of an automatic chronograph, which reignited interest in complicated horology and made people look at IWC differently. The innovative watch brought prestige to a brand mostly known for its more instrumental creations. Plenty of perpetual calendar watches are in the IWC collection, but you will not find a single Da Vinci reference in the current lineup. Forty years after its conception, it’s time for a remake of the IW3750.

I wouldn’t go so far as to accuse IWC of neglecting the Da Vinci. Still, it is unsettling to see the product family completely gone when you visit the brand’s website, especially considering the importance of the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar IW3750 from 1985. Currently, IWC is still riding the Ingenieur wave, but 2025 marks the 40th anniversary of the legendary “QP.” In other words, it’s the perfect moment to reintroduce the watch. IWC doesn’t even have to go through the trouble of developing a completely new concept to do so. Fellow Richemont brand Vacheron Constantin started the rebirth watch in 2022 by releasing the 222 in gold, and this year, a steel version debuted. In 2023, IWC presented the true-to-the-original Ingenieur, and last year, Piaget introduced the glamourous Polo 79. The recipe works with different ingredients, so to speak.

The time is right to reintroduce the IWC Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar IW3750 from 1985

The recent introduction of the Vacheron Constantin 222 in steel made me wonder if any interesting watches are left to reintroduce. I thought of two — the Rolex Oysterquartz and the IWC IW3750. The Oysterquartz debuted in 1977, and apart from the fact that only two of the discontinued models will celebrate their 50th anniversary, Rolex presenting a watch outfitted with a quartz movement in 2027 is highly unlikely. You can dream about a new solar-powered Rolex quartz movement all you want — I do, to be honest — but it’s not happening. Seeing the IW3750 come back to life is a much more realistic idea.

Swimming against the stream

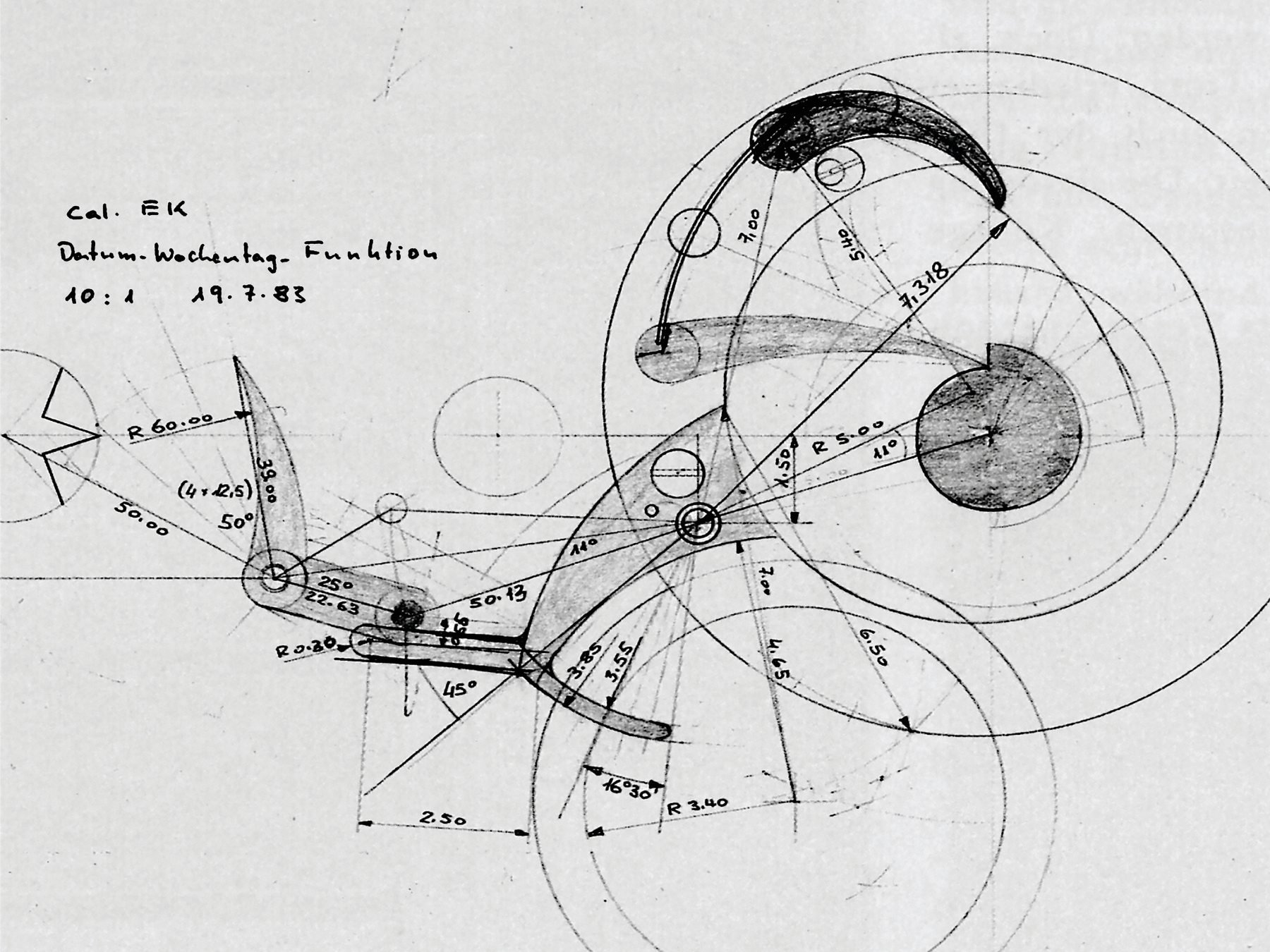

Two elements distinguish the Da Vinci IW3750 — the combination of complications and the design. Let’s focus on the technical aspects first. While Switzerland was being overrun by cheap quartz watches from the East in the late 1970s, watchmaker Kurt Klaus was working on a movement featuring a triple calendar and moonphase module, the first ever for the brand. The man working on the banks of the river Rhine, close to the famous Schaffhausen waterfalls, was swimming against the stream. But despite skepticism within the company, he continued his work. The efforts of the master watchmaker led to a successful limited run of the ref. 5500 pocket watch.

Then, it was time for Klaus to focus on wristwatches. He set his sights on the perpetual calendar. He was not going to create the very first wristwatch outfitted with a perpetual calendar mechanism (in 1925, Patek Philippe had a world’s first with the introduction of the 97975, and since this year marks that watch’s 100th birthday, be ready to see something extraordinary coming at Watches and Wonders). Still, wrist-worn perpetual calendars were rare at the time.

The Da Vinci miracle: 81 components and a four-digit year display

Klaus didn’t just build a QP for the wrist; he wanted to construct something user-friendly, not something associated with exclusive and traditional Haute Horlogerie but, rather, something that would fit the IWC philosophy. To state that the final timepiece was a tool watch would go too far, but the perpetual calendar module on top of the reliable Valjoux 7750 movement was a groundbreaking design made of just 81 components. Nevertheless, it displayed a four-digit year accurate until 2499 and a moonphase indicator accurate for the next 122 years.

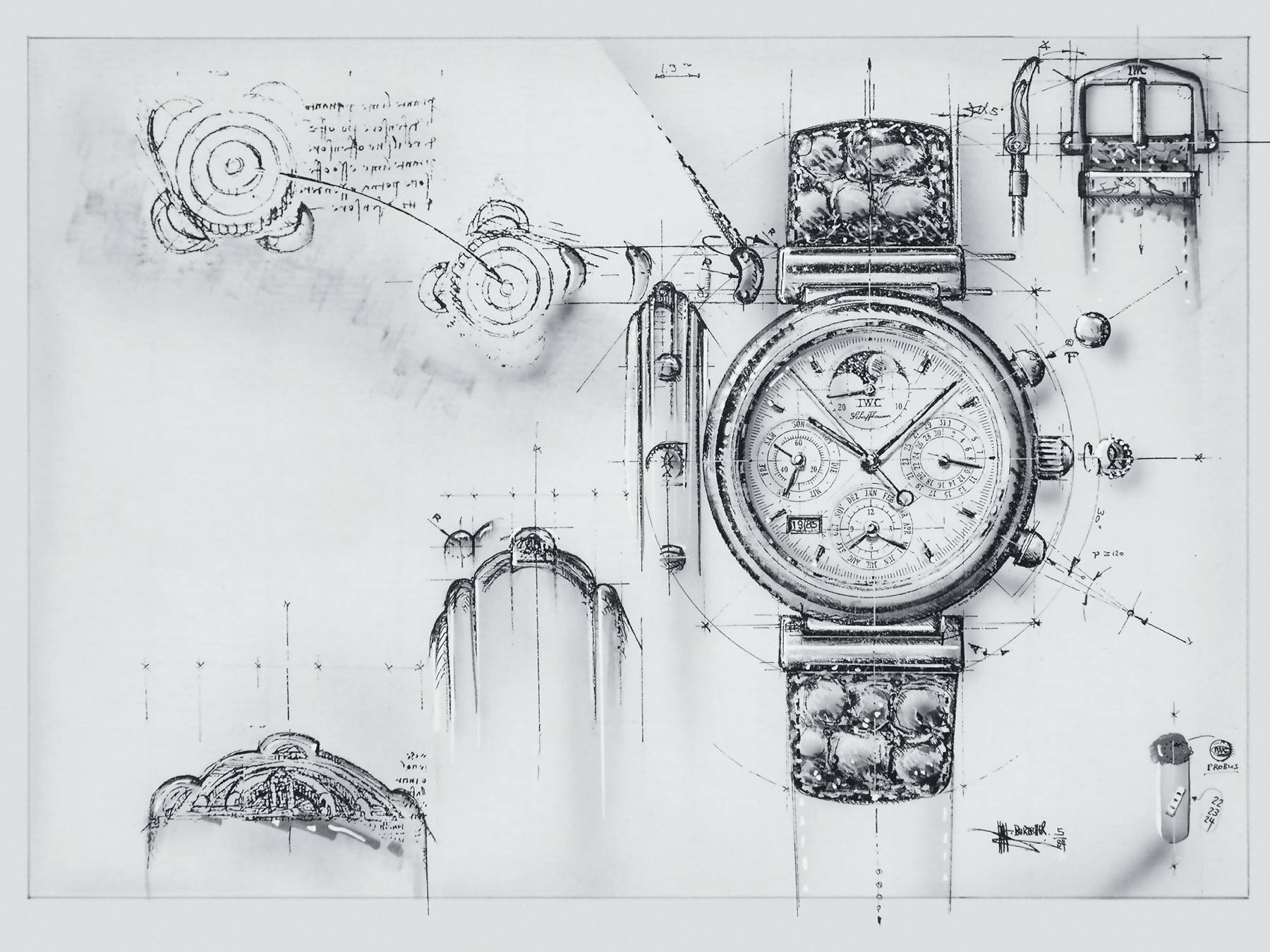

The movement was put in a watch designed by Hanno Burtscher. He created a baroque-like 39mm case with eye-catching and distinctive swiveling lugs. Appropriately, inspiration was found in Leonardo Da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus, a 12-volume bound set of writings and drawings. The drawings of rounded harbor fortifications in the codex made their way into the watch. When the complicated timepiece was presented at the annual Basel watch fair in 1985, IWC immediately sold 100 examples. Not only did that prove complicated watchmaking was still relevant, but it also showcased the competence of IWC.

2025: the year of the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar

IWC made two attempts to update the design language of the IW3750 but, unfortunately, never with great success. A third attempt was never made, causing the Da Vinci to disappear from the catalog. But a third attempt could prove more successful if IWC does what it did with the Ingenieur — stay close to the original and settle for just a few variations instead of creating a whole family.

I envision a Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar IW375025 in a 39mm yellow gold case. Rather than the original’s all-gold case back, the new version features a display back to show off the new movement. Like IWC, Vacheron Constantin, and Piaget did with their special re-editions, the watch’s looks must stay close to the original. Still, some updates are inevitable and also very welcome. For instance, a sapphire crystal instead of an acrylic one would be good. Also, using modern materials and production and finishing methods will bring this retro watch into the modern era.

Mixing and matching will get the job done

Kurt Klaus built his perpetual calendar, including a moonphase indication, on the foundation of a Valjoux 7750 movement. In the current IWC movement lineup, there is something similar available. It’s the 69355, which is part of the 69000 family of self-winding chronograph calibers introduced in 2018. This 4Hz movement with a power reserve of 46 hours comprises 205 components. It is similar in design to caliber 79320, for instance, a movement based on the Valjoux 7750. And there you have it. Like the original, a caliber from the 69000 family is a suitable foundation for a QP movement for a future Da Vinci in a 39mm case. Furthermore, IWC has a 42mm Portugieser Perpetual Calendar in the collection. That watch is outfitted with the brand’s caliber 82650, and although I’m no watchmaker, perhaps its QP mechanism could be adapted to function with the existing chronograph movement.

Yes, 2026 could be another Da Vinci year

I think 2026 could be an even more wonderful Da Vinci year. Next year marks the 40th anniversary of the Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar IW3755-03 in black and IW3755-05 in white ceramic. These watches made history because of their ceramic cases matched with yellow gold. Like the original IW3750, these watches still look the part and are also important for IWC since the brand always presents itself as a leader in ceramic watches.

What’s interesting is that, some time ago, Brandon wrote about the Da Vinci IW3750 in the series Wrist Game Or Crying Shame. The poll results left nothing to the imagination: 83% of our readers said the watch was Wrist Game. Watches and Wonders 2025, here we come. Please don’t let us down, IWC.

Header image: Ticking Way