The Allure Of Japanese Independent Watchmaking: Part Two — Kikuchi Nakagawa

Does a Dufour comparison seem far-fetched, or perhaps too easy to reach for? This name hangs on a high branch of the horological tree, and I don’t reach for it on a whim. As with Naoya Hida & Co in my story here, the duo (that would be Dufours plural) of Kikuchi Nakagawa is yet another example of the quiet classicism we have come to expect from the more well-known purveyors of Japanese independent watchmaking. I find it intensely compelling when so much effort is put into the execution of beautifully simple three-hand watches.

You might find my personal non-chronograph bias shining through, but perfectly balanced minimalism is a visual delight. Though the term minimalism is a matter of interpretation. There is sparkle and flourish in the details, so minimalism is here defined by its lack of complications. And all the more to notice the impeccable Finissage. You might also find me using the word Obsessive again. This is not for lack of words in my writer’s vocabulary. There simply seems to be a hidden level 11 on a Japanese craftsperson’s perfection scale. It’s a level unknown to us simple Europeans, and boy does it intrigue me.

It’s all about the hands, baby

If the bare-metal craftsmanship of Naoya Hida is all about the dial, at first glance Kikuchi Nakagawa is all about the hands. This and an impossibly smooth case finish. I will confess I had to research the actual term, as these are not your usual baton, sword or Feuille hands. This is a different kind of swoopy elegance, spade hands, a term I did have in the back of my head, but the visceral way they reflect light casts such a spell it made me expect a less literal term. Nakagawa-san has a delicate flourish of form to the hour and minute hands that will immediately capture your eye.

It only takes a furtive glance at the case and hands of the debut Murakumo, and the subsequent Ichimonji to think they’ve invested in the German Sallaz polishing machine. Sallaz?

The explanation for the phonetic translation Zaratsu – as in the cases from Grand Seiko and Minase. But no. Yet the polishing is even more blindingly smooth and reflective. This ain’t no photoshop trick, but the only manufacturer we know of using the ancient movement part finishing technique of black polishing for the actual watch case. I’ll let you raffle through your mind’s horological archive for that term while I give you the back story.

Kikuchi and Nakagawa, the back story

Prior to the strong debut of their Murakumo, Yusuke Kikuchi produced watches under his own name, before teaming up with Tomonari Nakagawa in love for the 1930s and 40s wristwatch design, and an obsessive purity of line. A good pointer for the direction of Kikuchi Nakagawa would be the quote of producing watches that fit within “the most ambitious attempt possible within the design code” of early to mid-century Swiss design. This is a style instantly recognizable in the Murakumo being a distilled, perfectionist vision of a future-proof ref.96 Patek Philippe Calatrava. A Calatrava which never had the mind-boggling finish made possible by what is a technique developed for small components, namely black polishing.

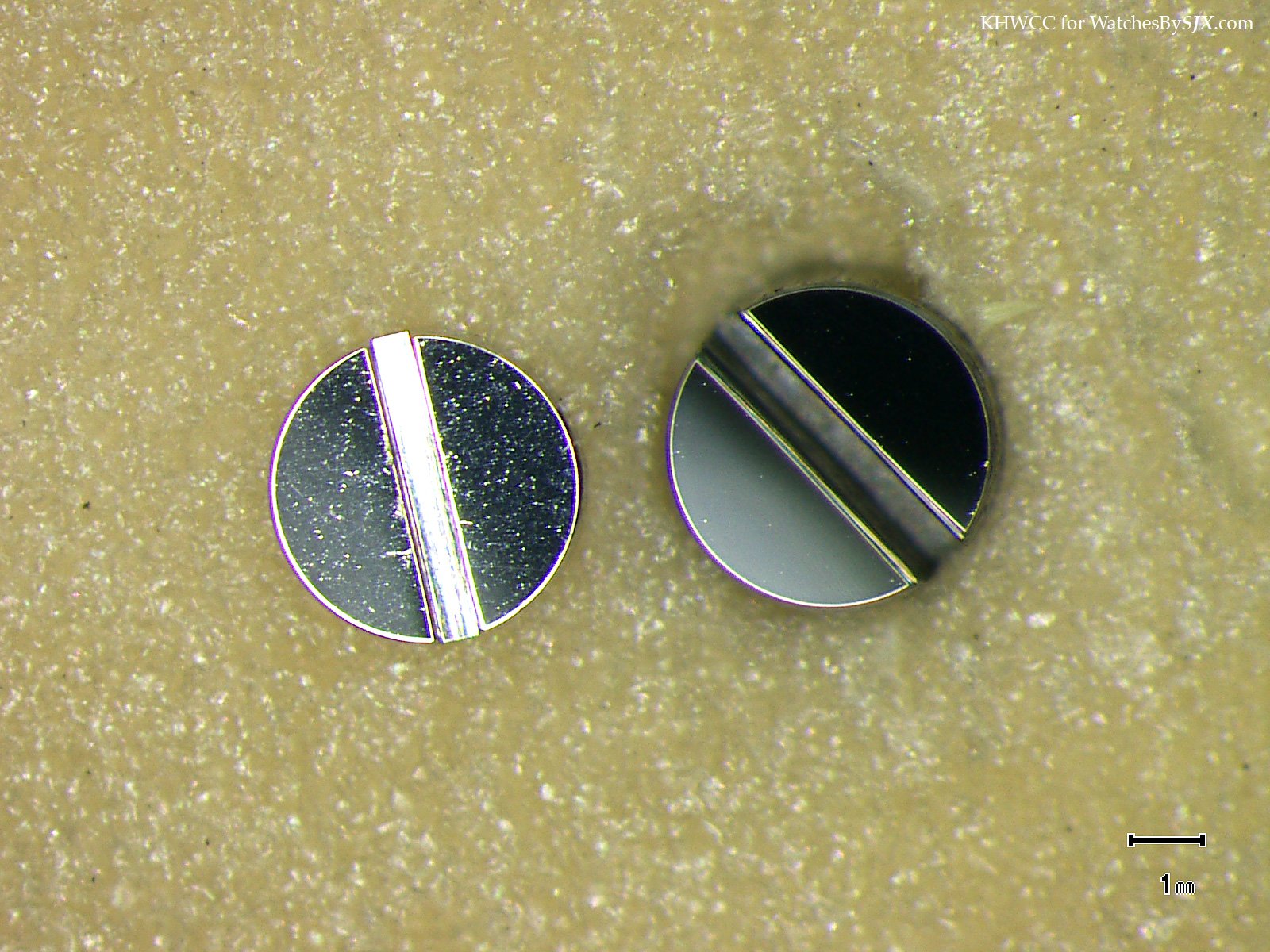

What an audacity, Kikuchi Nakagawa basing their production on main components receiving this treatment. To any sane Swiss watchmaker, it might seem impossible. To call Black Polishing unfeasible on a large scale, the term time-consuming would be a large understatement. Let me explain Black Polishing a.k.a poli noir briefly. Its raison d’etre is giving steel components a mirror-smooth surface. A finish so flat it will appear black from certain angles, hence the name. The polishing is usually done on a smooth zinc metal plate coated with a fine abrasive paste – most usually diamond dust in grease or oil, or aluminum oxide powder. The technique involves the component being moved around on the plate in a circular motion while applying mild pressure.

The joys of black polishing

Without going into further nit-picking detail, I’ll recommend this superb article by Watches by SJX, and simply prove my point by the image above showing an industrially polished screw next to a black polished, beveled one. I’ll leave you to ponder the time it takes to polish the Murakumo spade hands and the actual watch case itself, while we have a closer look at the model.

The Kikuchi Nakagawa Murakumo

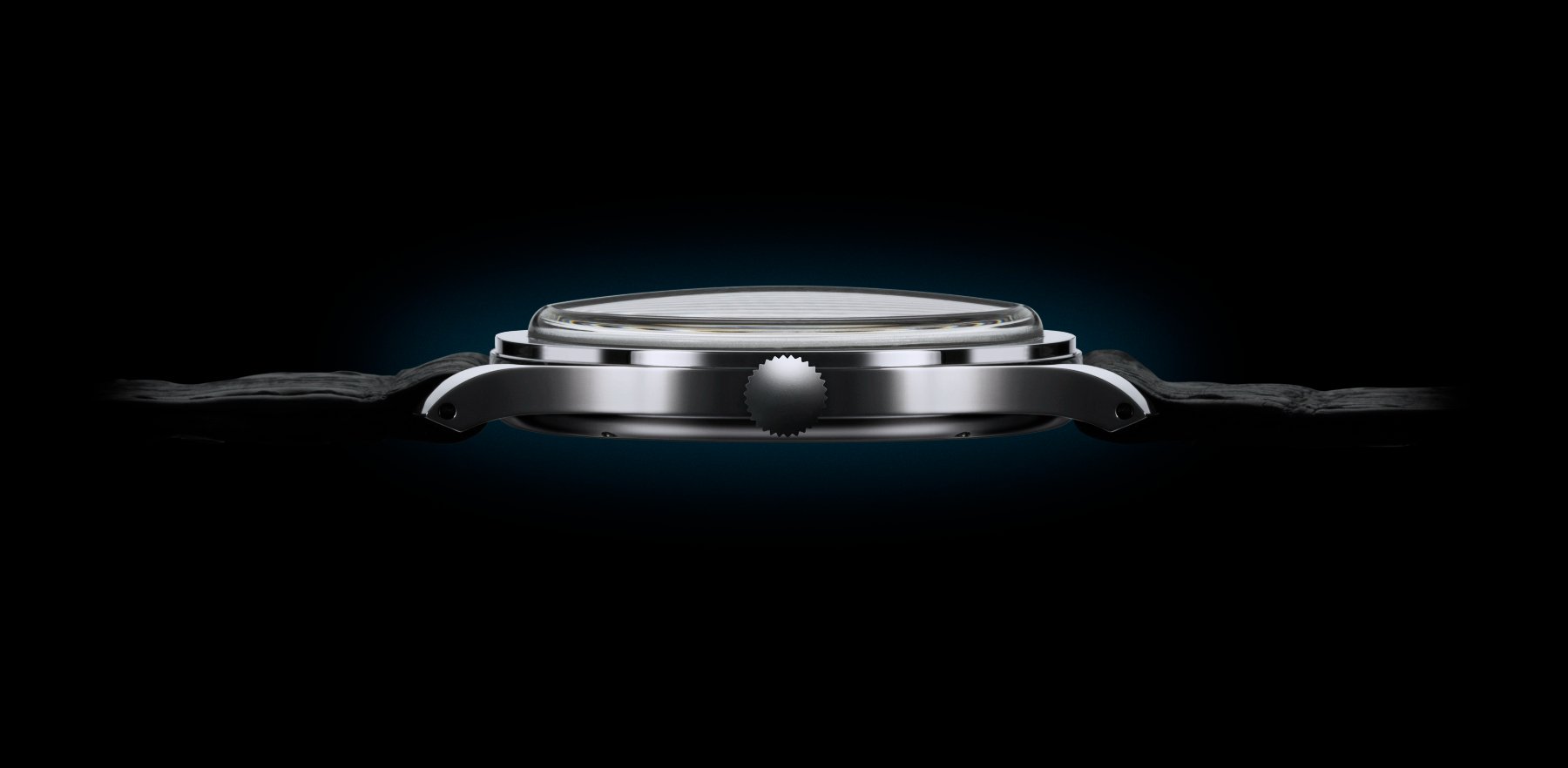

In the Murakumo, Kikuchi Nakagawa had a blisteringly strong debut into the world of Japanese independent watchmaking in 2018, and the Murakumo remains their most well-known piece of wristwear with a 24 month order lead time. Good things come to those who wait, and if you scrolled through my nerding out on black polishing, I can assure you, those 24 months are not exaggerating the mere time it takes to finish and assemble this very Japanese piece of Haute Horlogerie. On its unusually broad 22m leather strap, the sublime contrast of mirror-smooth surfaces and a monochrome black dial even comes across as dazzling on a small Instagram shot. So I fear an actual atelièr visit might seriously affect my perceived quality standards on how a three-hand – small seconds at 6 watch can be perfected. So with a view to an objective eye on reviews going forward, better not.

The dark formality has a distinct flair, speaks its own language, and the Murakumo does this with a strong but delicate whisper. True in size to its vintage inspiration, the case is 36.8mm by a very slim 8.5 in height, close to perfection. What seems an extraordinarily wide strap was the fashion of the early forties and especially in Pateks like the ref.96. While this was a today very small 31mm, the proportions are recognizable and work an elegant treat. A dynamic sweep of lug gives the slim Murakumo a slender stretched-out look that will make this wear larger in combination with the broad strap. This simply means all the more dial, not to mention hands, to enjoy while noticing similarities and also improvements (how dare I) to the Patek in addition to the contemporary sizing.

Timeless design

The case, produced by specialist Matsuura is a classic step-bezel steel case seen through the uncompromising loupe of Kikuchi Nakagawa. The black polishing sets an impossibly smooth stage for a dark abyss-like dial. There is no getting away from the fact that your eye will first catch each intricate detail. Those hands though? Perhaps the best spade hands in the business. And while you might think that black polishing was a time-consuming process, imagine what it takes to finish these. These are complex, rounded, three-dimensional shapes.

Those hands though? Perhaps the best spade hands in the business.

A polished stage show for a hand fetishist? Maybe, but does it take up too much attention on the grained, matte black dial? I beg to differ. Not only because I sense a growing infatuation, but for the sheer flamboyant move of it all. Yes, the spade hands are nabbing a lot of attention, but bring a whimsical flourish to a rather formal scene. And yes they match the mirror shine of the case, something a pair of timid Patek Feuille hands just wouldn’t. The rest of the dial is classicism incarnate, a simple minute track with immaculate Breguet numerals. The logo sits sharply proportionate between 12 o’clock and the dial center.

The Details that Matter

An oversize small seconds register at 6 might seem overtly classical, but is one of my favourite dial details. Kikuchi Nakagawa has it prominently recessed and detailed with a single Feuille pointer kissing the railway track. Did you notice the cheeky improvement to a classic Patek? Chopped numerals at 5 and 7 inspire frustration, their tops lobbed off by the small seconds register. Not here. Sir(or M’lady) has a silver dot inside each of the two hour markers. They have no relation to any other shape within the dial, yet look just right. Another small clue to the stubborn nature of Kikuchi and Nakagawa’s design ethos in creating the sublime Murakumo.

Under the case back of the Murakumo is the slim Vaucher VMF 5401 automatic movement helping the watch stay within its wrist-hugging 8.5mm height. Top-tier Swiss brands like Richard Mille and Parmigiani use the VMF 5401 for good reason. Recognizable with its sunray-formation Côtes de Geneve decoration and off-center tungsten rotor, it speaks to me. This is a big step above the norm of ETA and Sellita calibers and visually arresting. This intricate heart runs a 48-hour power reserve at 21,600v/h and underlines my conclusion. Kikuchi Nakagawa Murakumo hits the bullseye with classicism re-interpreted through a decisive twist. So much so that I’d happily have it on my top five list of Grails.

For more information on this Japanese independent, check out the Kikuchi Nakagawa website here.