Just My Type! An Interview With Watch Typography Designer Samuel Baker

If you follow my writing, you know I am an advocate for typography in watch design. It is an often-overlooked element that can make or break a watch. While I was developing my watch, typography designer Samuel Baker appeared on my radar. We ended up collaborating, resulting in a fully tailor-made typeface for my fledgling watch company. Samuel is deeply passionate about the subject, which you immediately feel when you speak to him, so I figured who better to share some insider insights on typography with us?

I covered the basics of the topic in this earlier article. If you are new to the fascinating world of watch typography, you may want to start there before proceeding with this interview.

How technical challenges influence typography

We jump straight into the ways technical advancements change dial type. Again, this builds on the information shared in the earlier article on the topic.

Thomas van Straaten (TVS): How did the technical challenges influencing watch typography change over the decades?

Samuel Baker (SB): You can almost discuss it in terms of centuries, not decades! The pad-printing process we talked about previously (aka tampography or décalque) has been around since the late 19th century and is still — fundamentally, at least — the predominant method of printing onto watch dials. Before that, dial markings were mostly either painted, enameled, or engraved by hand.

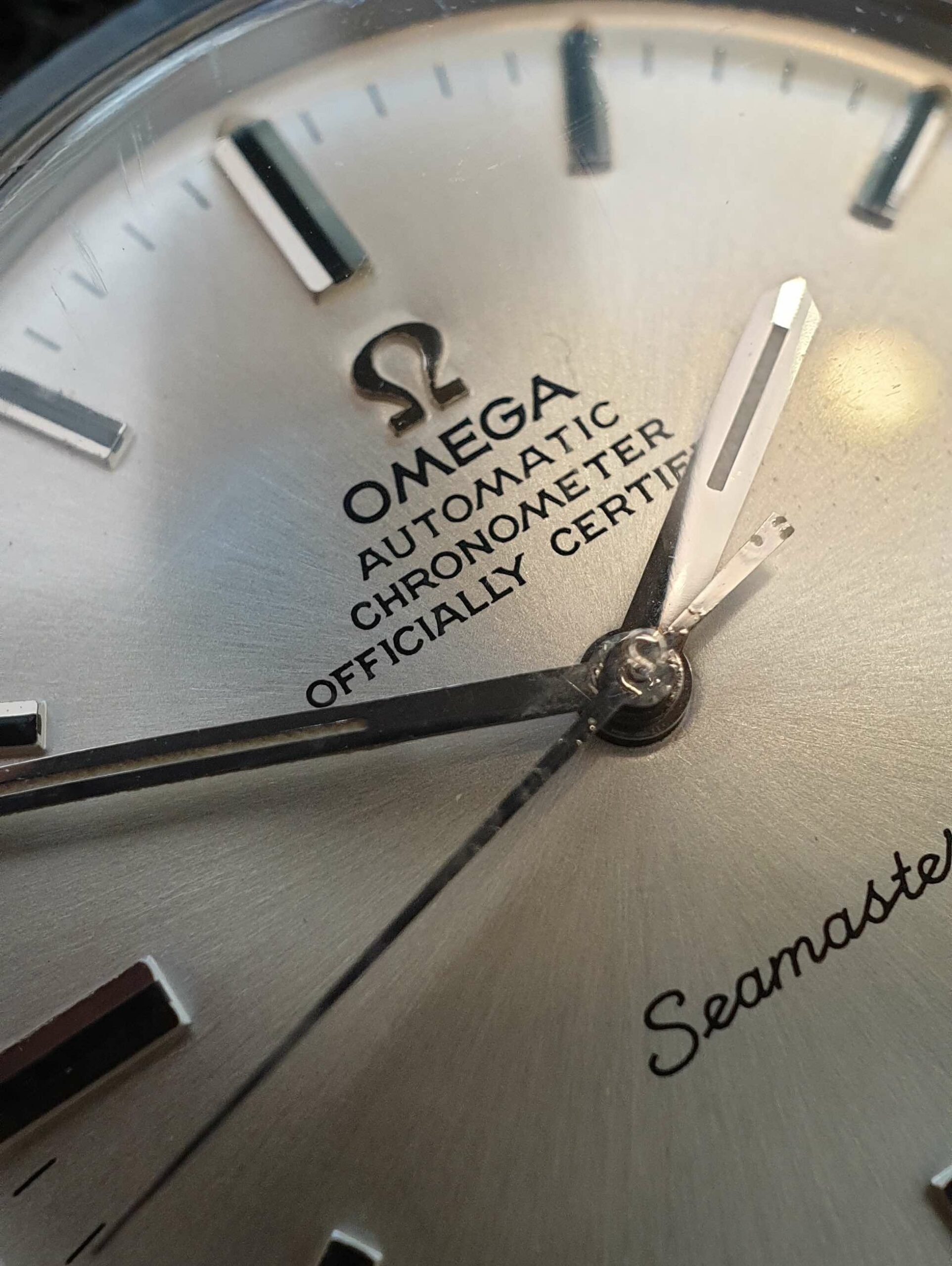

Some dials used a cartouche method (which you still sometimes see today), which is like a little applied plaque, engraved with the maker’s name or a dial numeral. But those early hand-painting and engraving techniques informed a lot of the styles that we still see and recognize as the vernacular of watch typography, not least because, at first, the metal plates that trap the ink (the cliché) were manually engraved, so they have the characteristics of engraved letterforms.

Later, chemical etching of those plates became the norm, leading to the photographic transfer of designs, which allows for scaling. This can change the appearance of the characters quite a lot because they don’t have to be drawn at a 1:1 scale (which, on a watch, is very small). Scaling down will result in cleaner, sharper lines, and you can also composite multiple elements in more sophisticated ways. Nowadays, artwork is created digitally, and the plates are engraved by laser. However, the printing is still fundamentally done with an engraved plate and a gelatin or silicone pad (except for cheaper digitally printed watches, like Swatch).

Generally, you can say that pad printing has become sharper and more precise over time. But you could also argue that it has removed some of the character that the imperfections and hand-drawn type created.

How to look at typography

TVS: Can you tell us how to evaluate watch-dial typography? Walk us through the things you look for.

SB: If I can look at a watch without being distracted by a clumsy bit of type, that’s a good start! The typography needs to make sense within the overall design of the watch. If there are indications, sub-dials, and so on, what they all mean should be clear, and you should be able to read them. Fundamentally, the type is there to serve a purpose. After that, it’s about execution — is it beautiful, elegant, traditional, bold, novel, stylish? What qualities is it trying to convey other than just the information? What’s appropriate for the brand and the purpose of the watch? What does it say to you? Do you like looking at it? Does it evoke something that you connect with emotionally? Not every watch has to do that, of course. Stark functionality can also make for a great design.

TVS: What constitutes great watch typography for you?

SB: Good watch-dial typography is like most other good typography — it should be legible, balanced, well spaced, and well laid out. It should understand the context within which it exists. What I mean is that it needs to be appropriate. It doesn’t have to be reserved or conservative (or even legible, I suppose!); it can also just be fun or unexpected. It can just make you smile when you look down at your wrist. I really liked the recent Paulin collaboration with OH no, a type foundry in California.

For me, it becomes great when it all just clicks and the dial layout “sings.” Very complicated dials can be extremely hard to get right, but so can very simple ones.

TVS: What constitutes bad watch typography for you?

SB: Laziness. When a brand hasn’t bothered. If you’re a watch brand using Arial on your dial, you either don’t care about details, or you can’t see the difference. Neither is a good look.

Another example of bad practice that you see all the time is digital distortion/stretching of type (usually to squeeze the letters/numbers into a specific space). When you do that, the strokes of the font get messed up — they get thicker in one part of the character and thinner in another. If you’re a typographer, that sticks out like a sore thumb.

If you look at a vintage Rolex date wheel, there will be three different number 2s — one for the 2, one for 12 and 21, and one for the rest of the 20s. This is because you want to fill the date window to maximize the size of the numbers for legibility. When drawn by hand, these 2s will all have the same stroke thickness and feel to their curves; it’s just that they are narrower or wider as required (rather like using a condensed or extended font but bespoke to the exact requirements of the design).

Most modern brands simply type the numbers out and stretch them to fit the window aperture. The tall date window at 6 o’clock of the current Omega Aqua Terra line is an example of this. Omega uses a version of Futura, a classic modernist font, and distorting those geometric forms to squeeze the numerals in is quite jarring (to me, at least).

The current use of typography

TVS: What would you change about the way brands handle typography today?

SB: I’d like more brands to give the typography the same level of attention they do to things like finishing, movement design, materials, and so on. Hire a professional! Watches are incredibly detailed and complex things with so many hand-crafted elements. Don’t short-cut the type or use a word-processor font, especially when it’s right there, front and center, every time you look at the watch. I find it a shame that some of Patek Philippe’s finest watches read “TOURBILLON” on the dial in Arial. When you look at the exquisite quality of some of the vintage Stern Frères dials for Patek, it feels like a connection to watchmaking craftsmanship has been lost there.

I should mention that I think a lot of young brands — the microbrands — are quite strong in their design and typography. A lot of the time, those brands have been founded by someone with a strong sense of design and aesthetics; and when you’re a microbrand and don’t design in-house/proprietary movements or have a hundred years of brand heritage, design is one of the things you can compete on.

TVS: Can you share with us some watches that absolutely nail the typography in your eyes?

SB: I saw a phenomenal Heuer Cortina on Instagram the other day. All the type is rendered by hand and beautifully spaced. Legibility is off the charts, and there’s even some flair in the details. It is a flawless execution.

In terms of modern watches, the custom numerals of the Berneron Mirage 38 are a great piece of work, really sophisticated, and in line with the watch. Nivada has managed to create vintage revivals without messing up the vintage type. I also want to mention the Grand Seiko SBGE285 and -283 GMTs, for which the brand developed a new numeral typeface for the 24-hour bezel. Of course, it’s heavily inspired by the five-digit Explorer II, but it’s executed well, and it blends perfectly with the design as a whole.

Designing type for watches

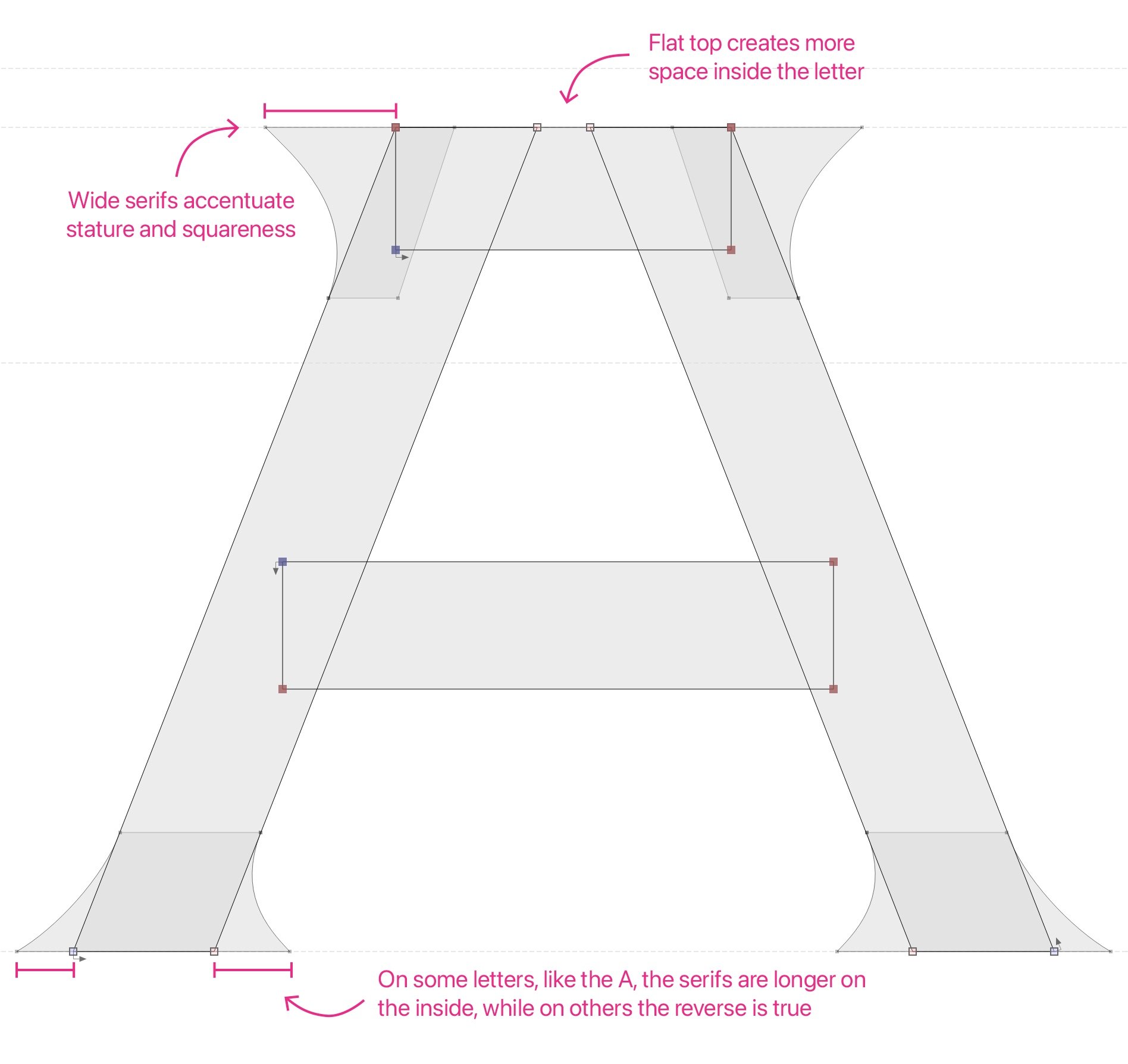

TVS: How do you approach designing a new typeface for a new watch? How do you translate brand and design into type?

SB: To begin, it’s a discussion about the brand’s values and its goals for the watch. That might involve a mood board of things that the brand likes and dislikes in other watches and other fields of design. Sometimes there is a desire for a very vintage feel, but sometimes it’s more modern, and sometimes it’s a combination of the two.

The idea of “classic design, modern build” is quite popular at the moment. People don’t necessarily want a vintage replica; they want modern performance and reliability, but they want a classic or timeless look to the design. So it’s about finding an execution that fulfills that brief. There are certain cues you can add to a typeface that will immediately evoke a particular design language or period. Changing a curve or a stroke ending can make something look decades older or decades more modern. It’s about balancing that until you get to the right look and feel. Mostly, it is about getting to something that just feels right.

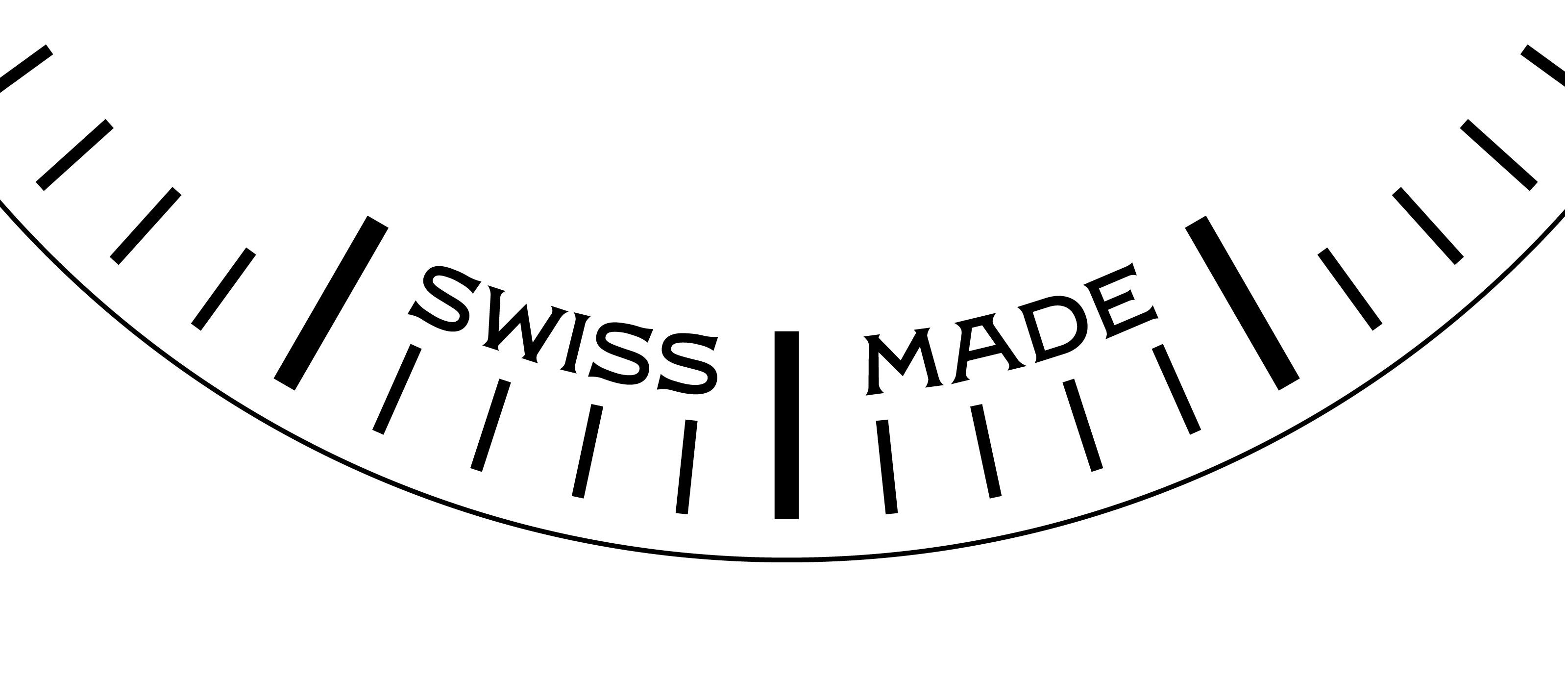

TVS: How about typography beyond the dial? Do you have any thoughts on bezels, case backs, etc?

SB: Bezels are interesting because they’re often some of the largest types on a watch. In the case of a diver’s watch, that typography is critical to the function, potentially even to someone’s life in certain situations. You certainly approach it differently from writing “Swiss Made” as small as you can at the bottom of the dial!

There’s also the question of different materials and techniques. Bezels aren’t pad printed. Markings are usually either anodized onto aluminum inserts, engraved, or molded in ceramic. That changes some of the style requirements. You don’t have to deal with ink spread, but you have to deal with other challenges, which might often change your style. The same is true for case backs. Traditional case-back engravings, if not hand engraved, are more likely to be monoline, no serifs, etc. Traditionally, you design for the application and the manufacturing processes.

However, it was interesting to apply the VPC font to the design of the Type 37HW’s case back. I was expecting to need to change it a little because of the engraving process and the curvature of the text, but it came out very nicely with minimal tweaks.

TVS: Is there anything else you would like to mention before we finish?

SB: I just want to thank you for giving me some space to talk about this. I’m aware that watch typography is a niche within a niche. It’s certainly not the most important thing in the world, so I’m just happy when anyone takes notice of it!

Closing thoughts on typography

Samuel is right, of course, when he says this is a niche within a niche. Still, I feel this does not quite do the subject justice. I love how he points to the emphasis on design and crafts in watchmaking. If brands celebrate hand-beveling and guilloché work, why not also celebrate hand-lettering or type design in general? If you ask me, the impact is equally significant.

I would like to thank Samuel Baker for taking the time to answer my questions. Hopefully, we have made the subject a tiny bit more prominent in the collective horological conscience.

What watches do you particularly like or dislike for their typography? Let us know in the comments below!