Nanotechnology Brings Seismic Potential to Watchmaking

Referring back to a recent post here, one can appreciate a world-first gasket free case mechanism, developed by a young independent brand Mauron Musy, is no mean feat.

What brought us here today, however, is a fascinating comment left under that post. An idea about combining such innovation with advancements in nanotechnology that may benefit our craft in some truly seismic ways.

I love our readers’ inventiveness.

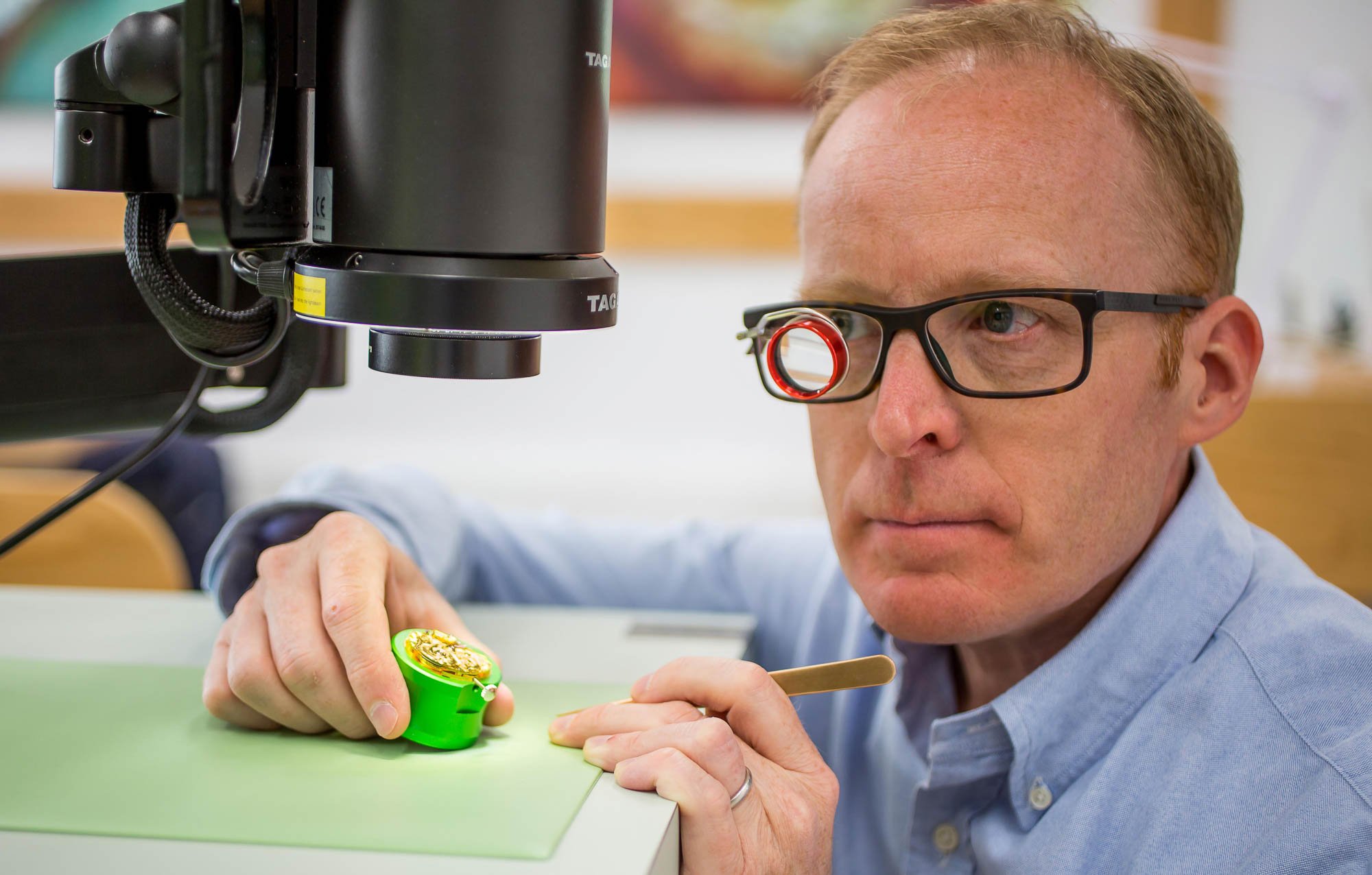

Roger Smith

The said nanoscience pursuit for a watch mechanism is fittingly led by another independent watchmaker, one of the highest prestige in horology, no less. At the forefront of this is Dr Roger W Smith OBE, based on the Isle of Man, who is continuing Britain’s long tradition to advance timekeeping with new inventions. Britain’s international significance may have drastically dwindled throughout the 20th century. Smith is determined to maintain and build upon the legacy of his mentor, Dr George Daniels, inventor of the famous co-axial escapement bought by Omega, which you must all know too well.

The age-old problem in watchmaking is friction.

Daniels and Smith have always been famous for their incredibly traditional, painstakingly particular methods. This new venture is proof that Smith and his talented team can also strive to be the first to potentially master a new scientific application. One that could literally enable a watch to run for one or several lifetimes without the need of any attention.

Optimal efficiency

Let us set the stage for you.

The age-old problem in watchmaking is friction. That is the enemy against which watchmakers must wage war. Even if the mechanics themselves are as efficient as they can possibly be, friction between components will result in wear and tear over time. Correct lubrication can increase the longevity of components, but cannot protect itself from the effects of time. After several years, even the finest lubricants start to coagulate, dry, flake, crack, or migrate, necessitating a service and overhaul to keep the movement running at optimal efficiency.

Removing the need for lubrication would theoretically remove the need for after-sales servicing, barring any kind of external damage, or a shock so significant the internal components themselves might sustain damage.

Nanotechnology

Now, we get down to the technical.

There have been a few ideas about how this may be possible in recent years. Replacing traditional materials with silicon alternatives was one idea bandied around for a while given silicon’s remarkable tribological properties (it is effectively self-lubricating). But that step proved too far for the purists. Although clockwork is more interesting to look at than a quartz module, knowing that each component was effectively processed rather than made kind of destroys the magic a bit.

That kind of short-cut would never fly with a brand as meticulous as Roger W Smith. No, what would be far more palatable would be a solution that employed traditionally crafter components made from traditional materials to a traditional aesthetic, and an alternative to traditional lubricant that protected these components from wear and tear.

It would seem that nanotechnology is the answer.

Roger Smith has formed a partnership with a team of research scientists from Manchester Metropolitan University to explore its potential. Although this is not the first time a watch brand has toyed with the idea of bringing this technology over to watchmaking (Jaeger-LeCoultre looked into the possibilities about fifteen years ago but ultimately abandoned the project), the last decade has seen much progress in both fields, meaning the time may be ripe for a fusion for the future.

Dry Lubricant

Here is the science part.

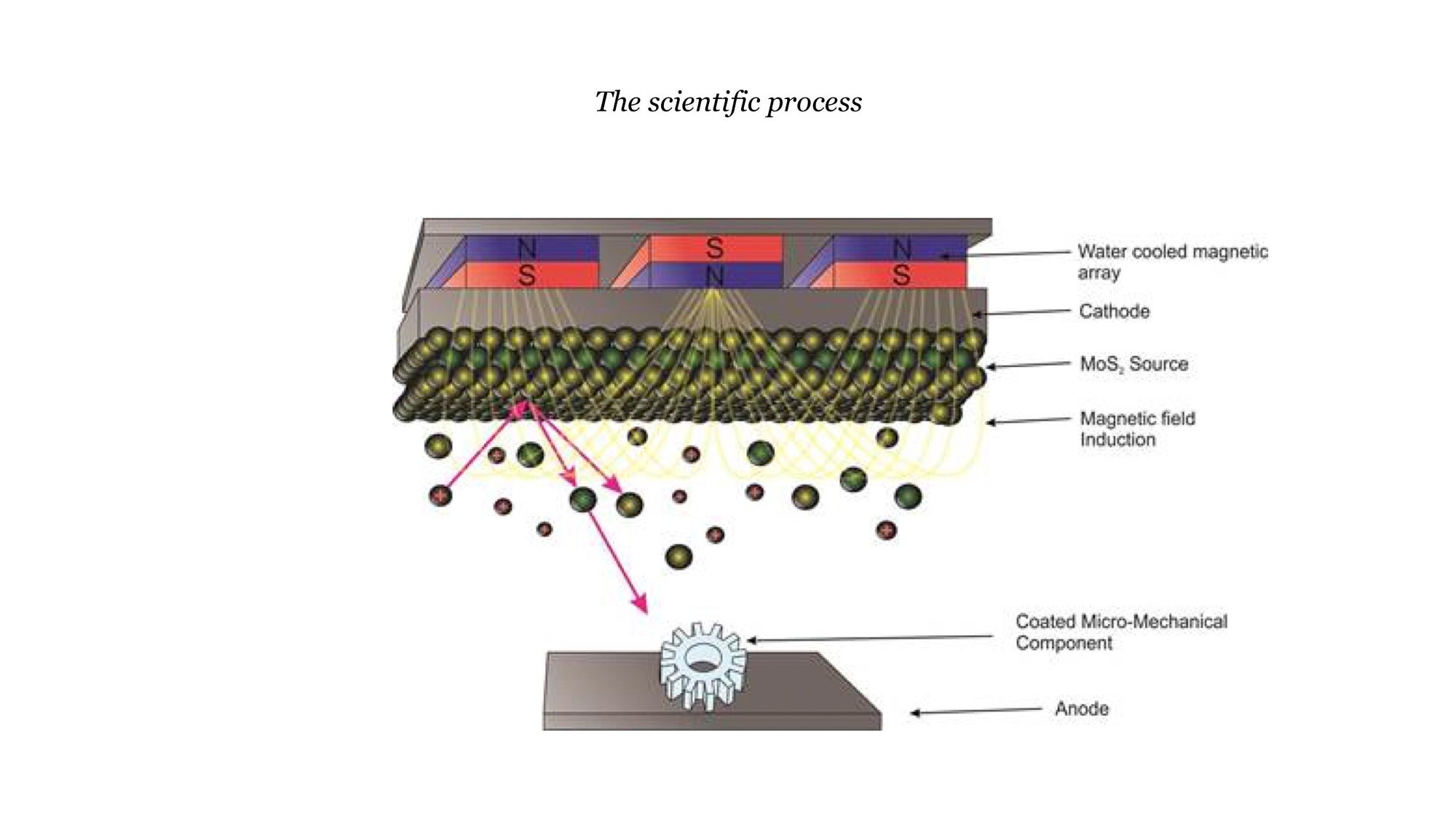

Dr. Samuel Rowley-Neale and Dr. Michael Down, both research associates at the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Manchester Metropolitan University, are leading the project. Their aim is to create virtually frictionless nano-coatings using molybdenum disulfide. Perhaps most relevantly, is the mode in which this lubricant is applied. Rather than being applied by hand, the molybdenum disulfide is deposited onto components using a magnetron sputtering process. The application of these 2D nano-materials to the surface of a part creates an incredibly fine and durable coating that is, in essence, a dry lubricant.

It will not age. It will not need replacing. It does not, unlike the oils we use currently, have a shelf life.

Admittedly, a lot of this doesn’t make intuitive sense to our human brains, but trust me, it’s legit. Even though we instinctively envisage lubricants as, well, wet, dry lubricant is nothing new in watchmaking, and has been used intermittently (depending on each individual company policy) in the lubrication of escapements for years and years.

What we have here though is a new type of dry lubricant that effectively becomes part of the part it is lubricating. The fact these nano-particles are bonded to the surface of the component eliminates the possibility of oil migration (which, in a traditionally lubricated watch, could leave the intended location under lubricated as well as creating problems for other components that come into contact with the escaped oil, and even the isochronism of the watch should that migrated oil reach the hairspring itself).

But more to the point, its dry and static nature means it will not change. It will not age. It will not need replacing. It does not, unlike the oils we use currently, have a shelf life. This means that the creation of (literally) generational timepieces could be just around the corner.

Less concern about depreciation

And while this is a fantastic step for the industry, it is even more important to general watch buyers who want to consider lesser known independent brands. The Roger W Smith brand is too esteemed and too important to the industry to worry about consumer suspicion. But one of the most frequent concerns I hear from people considering purchasing from a new, smaller independent, is whether or not they will still be around in 30 years to service the watch. Now, obviously, one sure fire way to not be around in 30 years’ time is to not sell any watches because everyone is afraid they won’t be around in 30 years’ time (a bit of a catch 22). But if you can purchase watches that won’t ever need servicing, then your choice will expand with less to concern about depreciation.

Given the testing of a working watch is due to complete in 12 months, there’s still some way to go when this experimental technology is rolled out to the masses. That said, the fantastic potential is certainly foreseeable to provide a better product for the end consumer. And from an independent perspective, anything that aids in that pursuit is absolute gold dust.