A Brief History Of Time: Oris’s Complete Brand History (1904–2021)

Since 1904, Oris has strived to make fantastic watches at accessible prices. The brand prides itself on its dedication to this mission, seeing it as an inseparable part of its identity. Through the years, watch enthusiasts have come to love Oris for this commitment to value. Indeed, this is one of the core values upon which the brand was built over 115 years ago.

In this installment of A Brief History of Time, we’ll explore as much as we can about where Oris came from, its struggles, its accomplishments, and its modern-day success. Admittedly, it’s a bit of a daunting task to fit such a long, uninterrupted history into a single article. Nevertheless, I hope you’ll stick with me, as we find out what makes this darling brand tick.

The beginnings of Oris

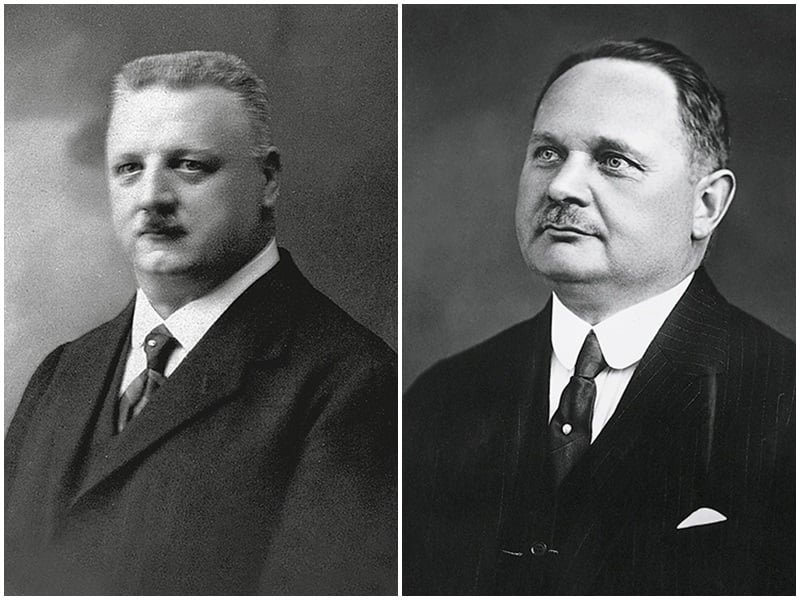

In 1904, Georges Christian and Paul Cattin moved from the watchmaking metropolis of Le Locle, Switzerland to the German-speaking town of Hölstein. The two men, intent to start their own watch company, purchased the recently closed Lohner & Co. watch factory, going into business as Manufacture d’Horlogerie de Hölstein Christian & Cattin on June 1st, 1904. Along with the Terma, Cinema, and Lucida trademarks, Christian and Cattin adopted the Oris trademark around the same time, taking the name from the nearby Orisbach tributary of the Ergolz river. From the very beginning, Christian and Cattin focused on producing affordable watches for the “everyman”. Watches across all of their trademarks used Roskopf-style movements with pin-pallet escapements. Due to the angles of the teeth on their escape wheels, these escapements required less fine-tuning than traditional Swiss levers and were easier and more cost-effective to produce.

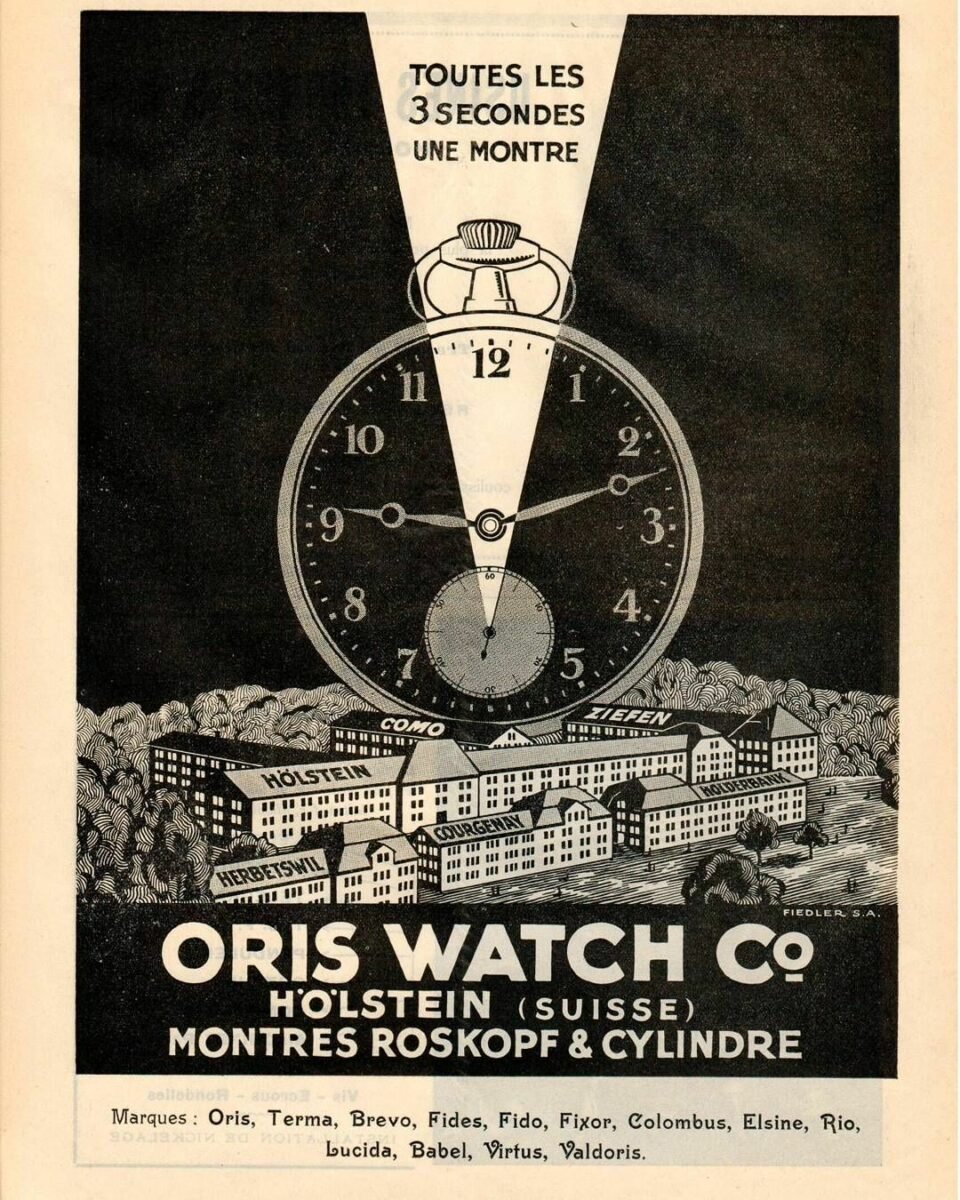

Advertisement showing all of the Oris factories. Oris’s sister brands, listed below, may have also been produced here.

Within a very short period of time, business was booming for Oris and its sister brands. In 1906, just two years after opening in Hölstein, the company opened another factory in Holderbank, and in 1908, yet another in Como. In 1911, the brand’s Hölstein headquarters became the largest employer in the town with over 300 staff. By 1914, the company had produced over one million watches. Oris then opened even more new factories, first in Courgenay in 1916, then Herbetswil and Ziefen in 1925. Oris dedicated its Ziefen factory specifically to electroplating, an important process in the manufacturing of its modestly priced timepieces. By the time all of its factories were up and running, the brand prided itself on its ability to produce “one watch every three seconds.”

The tides of change roll in

The second half of the 1920s brought changes to the company. In 1925, Oris responded to the growing wristwatch market, producing leather straps. These single-pass straps featured an additional bund-style piece with a formed leather cage to secure an Oris pocket watch to one’s wrist. Oris reportedly produced its first wristwatch for pilots in 1917 — a pocket watch with soldered lugs. Until a few years ago, however, modern-day Oris management wasn’t aware of this, and the company sees 1925 as the year it began manufacturing wristwatches in earnest.

This era also brought a change in Oris’s corporate structure. In 1927, co-founder Georges Christian passed away. That year, Jacques-David LeCoultre (of later Jaeger-LeCoultre fame) became president of Oris’s board of directors. The following year, George Christian’s brother-in-law, Oscar Herzog, took over Christian’s position as the brand’s general manager. He would hold this position until 1971, establishing the Herzog family’s legacy as stewards and leaders of the brand.

Oris must adapt and overcome

With Herzog at the wheel, things went well for Oris. Until 1934, that is, when the Swiss federal government instated Le Statut Horloger, or the “Watch Statute.” The law served as the precursor to the modern “Swiss Made” designation. It was intended to protect the worldwide prestige of Swiss watches, and discouraged “chablonnage.” This rather peculiar word that today means “covering pastry in chocolate,” at that time referred to the practice exporting watch movement parts and other components to be assembled abroad. The law established a “cartel” of mostly small watch brands, made up of 2,241 designated member companies. Of these companies, it required that 79% of them have less than 20 employees. The law limited certain business licenses only to companies the Swiss federal government deemed worthy, which were usually smaller, more exclusive manufactures.

Oris, however, employed hundreds of people, selling its watches at accessible prices. Victims of this success, Oris and bigger brands like it were not accepted into the official cartel of Swiss manufacturers. For these companies, the law hampered global expansion. More detrimentally, it also limited their access to newer Swiss technology and parts. Oris had historically used pin-pallet escapements due to their ease of manufacture and accessible price. It was becoming more apparent, however, that lever escapements were more accurate and durable. In order to improve its offerings, Oris wanted to upgrade its technology. Exclusion from the official watchmaking cartel, however, prevented the brand from adopting the lever escapement, as the cartel perhaps viewed it as “infringing” on its technology. Oris, therefore, had no choice but to innovate its pin-pallet escapements and prove their reliability.

Can’t stop, won’t stop

Despite the restrictions Oris faced, the company forged ahead. In the quest for more vertical integration, Oris opened its own dial factory in Biel/Bienne in 1936, and in 1938, began the manufacture of its own pin-pallet escapements. This brought more of Oris’s most crucial watchmaking operations in-house, allowing the brand to make the most of the cards the Watch Statute had dealt it. Around this time, Oris brought as many highly-trained watchmakers under its roof as possible and established itself as a leader in equality by offering equal positions to both men and women.

In 1938, Oris also debuted its first serially produced pilot’s watch, the Big Crown. The watch featured a black dial with gilt accents and gilt hands. Small seconds at six o’clock and a legible pointer date, indicated by a red-tipped central hand, were characteristic features of its era — one in which central seconds and date windows had not yet become mainstream. The most defining characteristic, however, was its namesake big crown. This utilitarian design choice made it easy for pilots to adjust the watch without taking their gloves off. The Big Crown has been an icon of the Oris collection since 1938, and today, it remains an enthusiast favorite.

During World War II, Oris faced a huge drop-off in sales and production limited to 200,000 watches per year. In order to keep business afloat, the brand began producing alarm clocks. As with most mechanical alarms, the clocks featured a central alarm-setting hand. Oris would produce these for decades to come in various shapes, colors, and sizes, with most in the 50-60mm range. This example is 57mm in diameter.

Oris expands again

After the war, Oris was able to resume its expansion. In 1945, the company’s pin-pallet escapement received its first designation of accuracy from the Bureau Official de Contrôle de la Marche des Montes (a precursor to the COSC) in Le Locle. Oris would reportedly go on to receive 200 of these distinctions in the next eight years. To properly staff its Hölstein headquarters, Oris offered a shuttle bus service to employees living up to 25 kilometers away. In 1949, the brand expanded its range of clocks to include a model with an eight-day power reserve. The brand then set its sights on the “watches of the future.”

Though the central-rotor automatic movement had debuted in wristwatches in 1931, Rolex had owned a patent on the technology. This left other manufactures to either produce bumper automatics or simply stick to manually wound calibers. In 1948, however, Rolex’s patent expired, and watch manufacturers chomped at the bit to get in on rotor technology. In 1952, Oris released its first automatic watch, featuring the caliber 601.

This 17-jewel rotor automatic beat at 18,000vph and featured both small seconds and power reserve indicators. A power reserve indicator on an automatic watch may seem redundant to us today, but at the time, automatic watches were still novel. Thus, it served as a reassurance to the wearer that the rotor was, in fact, functioning properly, rendering hand-winding unnecessary. The movement was housed in a 33mm chromed or gold-plated case, with gilt hands and indices. The silver dial featured luminescent pips to match the luminescent hour and minute hands. The model shown above is extremely similar to these first releases, but it features the caliber 605. This was an updated version of the 601, separated by only 16 different components.

Oris freed from restrictions

Though Oris‘s own pin-pallet escapement performed well, the company realized that it could not rely on it forever. With its sights set on upgrading to lever escapements, General Manager Oscar Herzog hired Dr. Rolf Portmann in 1956. Portmann, a young lawyer, saw how the restrictions of the Watch Statute were hurting not only Oris but also many other Swiss watch companies on the more affordable end of the market. If things didn’t change, foreign companies with rapidly developing manufacturing processes, like Timex and Seiko, threatened to overtake the Swiss industry. Negative sentiment about the hyper-exclusive Swiss industry was also brewing abroad. The President of Elgin even commented that American watch importers who did business with Swiss companies “support[ed] one of the most powerful monopolies in the world” and called for them to “limit transactions with countries whose industry is regulated by means of cartels.” The Swiss laws needed reform.

Portmann would spend his first ten years at Oris petitioning the government to overturn the Watch Statute. Other large watch manufacturers employed legal teams to do the same. The law underwent gradual reforms throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Most of the information (translated from French) that I can find on the details of these reforms has to do with import/export practices, with little in regards to the monopoly of technology by small, luxury manufacturers. By 1966, however, Oris was apparently granted the right to finally produce lever escapements, and today, the brand continues to honor Dr. Portmann for his role in this victory. Ultimately, the law was overturned in its entirety in 1971, replaced by modern Swiss Made standards.

Not just your daddy’s dress watch anymore

In 1965, Oris debuted a new purpose-built watch, the face of which any fan of the brand will instantly recognize. The Oris Waterproof, pictured left in the image above, was a 36mm diver that was water-resistant to 100m. It featured a uni-directional rotating bezel, black dial, and liberal amounts of tritium on its bezel pip, hands, and hour markers. The Waterproof housed the manually wound caliber 654. This in-house movement beat at 18,000vph, and featured center seconds, a date window, and a power reserve of 46 hours. Since it was released in 1965, caliber 654 still contained a pin-pallet escapement. Oris later updated the watch with the release of the Super, pictured right. It featured a new, simpler dial layout, and later versions featured the new-and-improved Swiss lever escapement caliber 484 as well.

Now free from restrictions, Oris was finally able to upgrade its calibers. The brand released an automatic dive watch, the Star, which contained the first lever-escapement movement in its arsenal, caliber 645. In 1968, the Astronomical and Chronometric Observatory in Neuchâtel awarded the brand its first chronometer certificate for the Oris caliber 652. While Oris says this movement used a lever escapement, most information I can find indicates that it used a pin-pallet escapement. Oris may have submitted a modified version to the Observatory, but for now, the details remain unclear. If it did use a pin-pallet escapement, that would only further confirm that Oris had produced a high-quality product.

It was the best of times…

In the late 1960s, Oris reached the pinnacle of its success, employing over 800 people between all of its factories. Having become one of the top 10 largest watch manufacturers in the world, Oris produced 1.2 million watches and clocks annually. The brand was on a roll.

In 1970, Oris released the Chronoris, its first chronograph. This 38mm watch featured the manually wound, 17-jewel caliber 725, developed by Dubois Dépraz. Although it was a chronograph, the watch featured a clean display with neither elapsed minute nor elapsed hour counters, showing only elapsed seconds via its orange chronograph hand. To track elapsed minutes, however, the user could simply align the internal rotating bezel with the minute hand before starting the chronograph. Oris produced the watch in two color variations — one with a tachymeter and orange/white bezel, the other with no tachymeter, and an all-white bezel.

Around this time, Oris had reached the top of its game. Not only was the company employing hundreds of people and producing watches on par with modern-day Rolex, but it was also building machines and tools in-house and training 40 engineers and watchmakers annually in its apprenticeship program. Soon, however, that would all change.

It was the worst of times

Anyone somewhat familiar with the history of the watch industry can probably guess what hit Oris next — the quartz crisis. With inexpensive quartz watches from Asia rapidly eating into its market share, the Swiss watch industry saw a massive number of company closures (about 1,000 in total from 1970-1983). In addition, many international markets were laden with political unrest, and the US suffered from both high rates of unemployment and massive inflation. These factors caused the relative value of the Swiss franc to rise dramatically, making Swiss exports prohibitively expensive for many consumers abroad. To prevent total industry collapse, groups like ASUAG (originally set up in the 1930s to save the watch industry during the Great Depression), haphazardly bought up many of the Swiss manufacturers, including Oris, with no clear plans for their development.

At this time, Dr. Rolf Portmann, the lawyer who had helped Oris so much in its fight to overturn the Watch Statute, took Oscar Herzog’s position as the brand’s general manager. Under group control, however, Portmann could do little to guide the brand. Though ASUAG had historically let its brands operate independently, the 1970s saw the group strengthen its control on its “underlings.” Oris was forced by ASUAG to produce quartz watches, such as the Acapulco seen above. Portmann saw this as contrary to Oris’ proud historical identity as a manufacturer of mechanical movements. In 1978, the former general manager’s son, Ulrich Herzog, would join Oris. Together with Portmann, he would envision a new future for the brand.

Breaking free

Under the thumb of ASUAG in the early 1980s, Oris was on the brink of collapse. In 1982, however, Portmann and Herzog were given the chance to purchase what remained of the company. Though it had lost its movement manufacturing capabilities, the duo saw the offer as an opportunity to reclaim the brand’s soul as a maker of mechanical timepieces. Portmann and Herzog purchased the brand from ASUAG and re-established Oris SA as a truly independent brand.

In the years that immediately followed, Herzog traveled the world, rebuilding Oris’s reputation and studying the market. What he found, ironically, was that although Japan had led the industry to quartz, Japanese customers felt a renewed passion for mechanical watches. Herzog recognized that the nation was indeed a global trendsetter. Thus, with renewed vigor and confidence, Herzog decided to abandon quartz altogether and relaunch Oris’s most iconic mechanical watch — the Big Crown with pointer date.

Though I am unable to pin down the very first reference, my research indicates that Big Crown models of this period were made with both manually wound and automatic movements (ETA 2688 and 2691 calibers, respectively), in a range of sizes from 32 to 37mm, and in steel, two-tone, and gold-plated cases.

New horizons

In 1988, Oris reached into its alarm-clock-making past and introduced its first alarm wristwatch with the caliber 418. Some sources claim that Oris used new-old-stock A. Schild 1930 alarm calibers. Others claim that Oris developed its own alarm module using a real gong, whose sound took months to perfect. Perhaps Oris refined the alarm mechanism of the A. Schild caliber. Regardless, reference 418-7xxx was a big release for the brand. The 34mm watch was available with a variety of dial colors, indices, and case finishes.

Oris Players, ref. 7412, for soccer/football (left) and golf (right). Image credit: Aucfree.com and Prescelto.it

In 1990, Oris adopted the “High Mech” slogan still in use today, cementing its commitment to mechanical timepieces. That year, the brand also released its Player’s watches. These 40mm pieces were inspired by soccer/football and golf. They featured both a timing bezel and a movement module with four push-button sport-specific counters on top of an ETA 2824 caliber.

New for the ’90s

Throughout the 1990s, Oris developed several movement modules that the brand still uses today. In 1991, Oris debuted its caliber 581. It featured a four-register module with day, date, moonphase, and second timezone indicators on an ETA 2671 movement. The movement found a home in several models, including the 34mm model seen above. In 1995, Oris debuted its first regulator movement, caliber 649. In true regulator fashion, it featured a decentralized hour hand and small seconds sub-dial. The ETA 2836-2-based caliber also included a date window.

Oris Worldtimer with caliber 690 and Full Steel Pointer Day with caliber 645. Image credit: Zeitauktion and 2ndstreet.jp

In 1997, Oris released its Worldtimer with caliber 690. The base ETA 2836-2 base featured a patented module with small seconds, a three-o’clock sub-dial for a full second timezone, and pushers at four and eight o’clock. Using these pushers, the wearer could adjust the both date and the local time forward or backward in one-hour increments. Oris was reportedly the first to offer a movement with this function. In 1999, the brand used the same base movement to develop its caliber 645 with a unique pointer day indicator.

Oris BC3 and Andy Sheppard Jazz collaboration. Image credit: Catawiki.com and Vintagetimewatches.com

Other notable models from the ’90s include Oris’s BC3 pilot’s watch and the Andy Sheppard watch, a collaboration with the London Jazz Festival. The 39.5mm BC3 provided a modern take on Oris’ purpose-built pilot watches. The 37mm Andy Sheppard limited edition of 350 pieces marked Oris’s first major non-watch-industry partnership. The watch was the beginning of a line of jazz musician-inspired Oris watches that continues to this day.

The new millennium

With a laudable range of modules and complications under its belt, Oris turned its attention in the 2000s to design and technical innovation. In 2001, the brand introduced the TT1, a sporty 43mm chronograph with a rubber bezel and a rubber strap. The doughnut-shaped case and integrated strap design would become a stylistic calling card for the brand. Eventually, the TT1 would morph into a diver’s watch, laying the foundation for the modern-day Aquis collection.

In 2002, Oris began using its trademark red rotor and introduced the Atelier collection, a line of dressier offerings that continues to this day. In 2004, the brand celebrated its 100th anniversary, marking it with the Centennial set. It was limited to 1904 pieces, and it included both a 42mm Atelier Worldtimer with caliber 690 and a mechanical 8-day alarm clock, recalling clocks Oris made over 50 years earlier. These pieces and the movements inside them marked some of the most historically significant mechanical developments in the brand’s then 100-year history.

The decade also saw some important technical innovations and collaborations for the brand. The Quick-Lock Crown of 2004 screwed down completely with just one 120-degree turn. The Vertical Crown on 2008’s BC4 Flight Timer was a unique control knob for the inner bezel. Finally, the Rotation Safety System of 2009 was a locking mechanism for a unidirectional bezel. It required the bezel to be lifted upwards, turned, then pushed down again to lock it in place, reducing slippage underwater. Oris collaborated with diver Roman Frischkneckt to design it, as well as Williams F1 driver Nico Rosberg, diver Carlos Coste, and the Swiss Hunter aerial flight team for limited edition pieces.

Tech and collaborations in the 2010s and beyond

Oris further cemented its reputation for purpose-built, high-quality timepieces, coining the slogan, “Real Watches For Real People” in 2010. The brand continued to advance its technology, starting with the Sliding Sledge clasp for its rubber straps. A new strap with barbed ends prevented the clasp from slipping off, while a sliding mechanism in the clasp itself allowed for quick adjustments without removing the watch. Oris released the Aquis Depth Gauge in 2013. The gauge allowed water into a pressurized channel via a tiny hole near 12 o’clock, indicating one’s depth as the water pushed the air around the channel. In 2014, the brand launched the Big Crown ProPilot Altimeter, the first automatic watch in the world with a mechanical altimeter.

Starting in 2010, Oris increased its partnerships with environmental organizations. The first of these partnerships with the Australian Marine Conservation Society saw the release of a limited edition dive watch of 1000 pieces to raise awareness and funds for the protection and preservation of the Great Barrier Reef. Oris continued the partnership in 2015 with a second model. The brand then partnered with several other environmental agencies, including the Lake Baikal Foundation, the Coral Restoration Foundation, and Everwave, releasing several Aquis limited editions to benefit them.

In-house movement development for the modern age

When the quartz crisis nearly put Oris under in the 1970s and early ’80s, the company lost most of its historical movement manufacturing capabilities. Under the leadership of Ulrich Herzog and Rolf Portmann, the brand had developed several in-house modules to use on top of ETA/Sellita movements. In 2014, however, Oris marked its 110th anniversary with the first movement developed entirely in-house in 35 years, Calibre 110. At 34mm in diameter, the manually wound caliber was well-suited to larger, modern cases. It featured 40 jewels and a 21,600vph frequency, as well as an astonishing 10-day power reserve from a single barrel. The central hour and minute hands were paired with small seconds and power reserve indicators on the dial side. The movement made its debut in the Atelier 110 Years Limited Edition, and it served as a perfect base upon which to add further complications.

More complicated calibers followed in the years to come, like Calibre 111 with a date window, 112 with a second timezone sub-dial and day/night indicator, 113 with a “business calendar”, and 114 with a central GMT hand, adjustable to half-hour increments. In 2020, Oris released its first in-house-developed automatic movement in decades, Calibre 400. This thoroughly modern caliber features a double barrel for 5 days of power reserve, a 28,800vph frequency, a cleverly designed anti-magnetic silicon escapement (detailed in this awesome watchmaker’s review), and a 10-year service interval.

Oris’s hits just keep on coming

In the last five years, Oris has had huge success with its Divers 65 and Big Crown in bronze and steel. The Aquis has proven to be a rock-solid foundation for the brand’s most capable dive watches. The ProPilot line provides rugged, legible aviation pieces for those with their eyes on the skies. Finally, the Artelier and Classic lines let even the more formally oriented among us get in on the Oris action. The brand’s dedication to providing technical, capable, and stylish at competitive prices has made it a major player in the enthusiasts’ market today, especially in the sub-€3,000 price range. I dare say that even Oris’s highest-end offerings, such as those equipped with the Calibre 11x, offer tremendous bang-per-buck. Try asking the same complications and specs from any other Swiss brand in Oris’s price range, and I’m afraid you’ll only be met with the sound of chirping crickets.

Since I began my watch journey in 2006, Oris has always been highly regarded among everyday watch enthusiasts. Simply judging from the fervor surrounding its releases in recent years, I don’t see that reputation going south any time soon. I do hope, however, that this article gave you a more complete understanding and appreciation for the brand.

Now, we’ll throw it over to you. What do you think of Oris? Do you own Oris watches? What’s your favorite in its current line-up? Most of all, what historical models did you find most interesting?

We hope you’ve enjoyed this history of Oris, and look forward to reading your comments below. Thanks, as always, for reading A Brief History of Time!