A Brief Overview of Gérald Genta — Designer Of The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak And The Patek Philippe Nautilus

You have probably heard the name Gérald Genta countless times if you have an interest in watch design. His name is synonymous with two of the most successful wristwatch lines in the modern era; the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and the Patek Philippe Nautilus. Numerous iterations have spawned from these core designs. And in the case of Audemars Piguet, the Royal Oak is the cornerstone of the brand’s design DNA, even 50 years after its birth.

So how did it come to be that two of the “holy trinity” Grand Maisons ultimately owe these successes to not just one designer, but the very same man? To understand this, you first have to understand the man himself — Gérald Genta, a legend of 20th-century Swiss watchmaking.

Starting with the basics

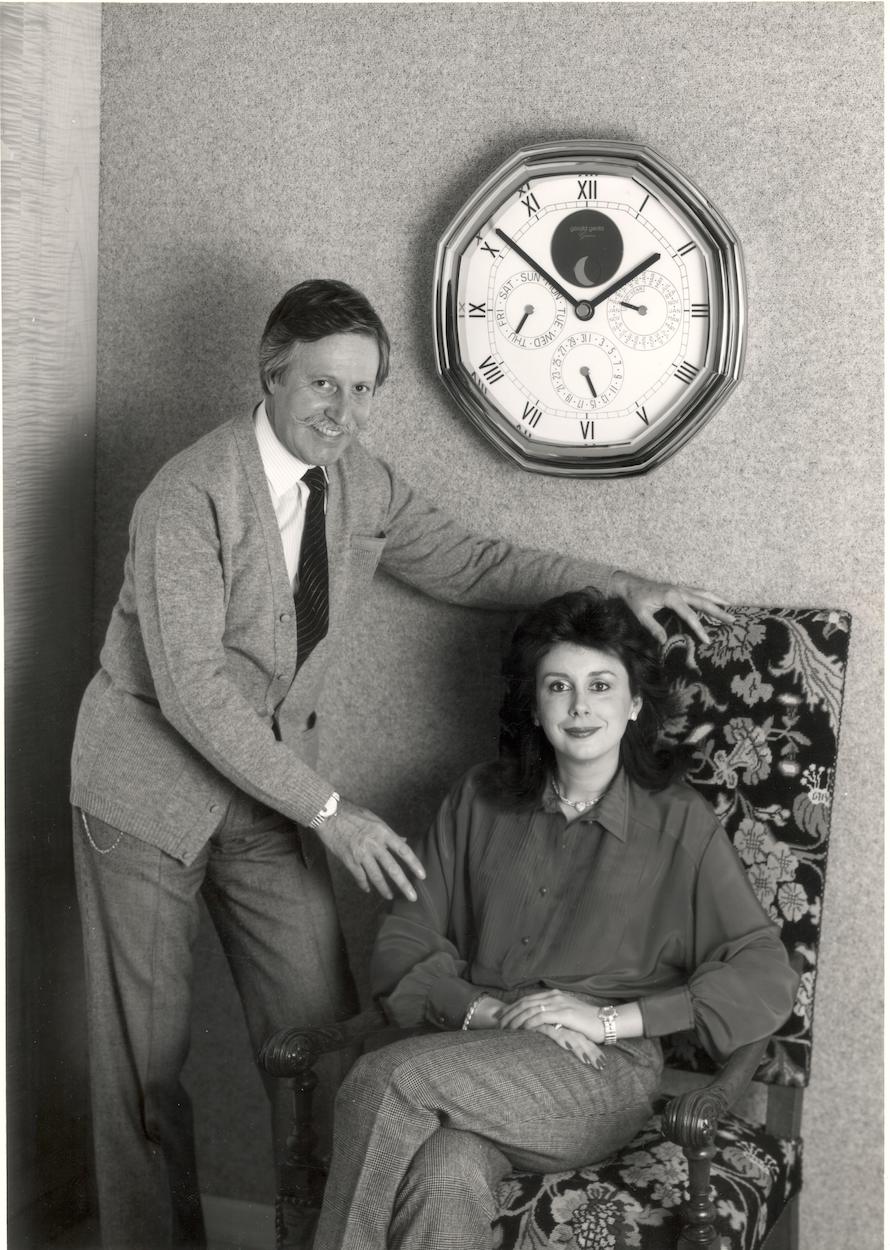

Charles Gérald Genta was born on May 1st, 1931 in Geneva, Switzerland. Throughout his 80 years on Earth, he blazed a trail through the watchmaking industry that still smolders to this day. He is survived by his wife Evelyne, whom he married at a grand wedding in Monte Carlo. In addition to her duties as a Monégasque ambassador for the United Kingdom, Evelyne maintains her late husband’s legacy alongside the couple’s daughter, Alexia. The familial duo established the Gerald Genta Association in 2019 — an event we covered here on Fratello.

Genta the artist

Genta was not a trained watch designer but worked as a jeweler who partook in art as a personal hobby. He painted daily and accrued a portfolio of nearly 100,000 art pieces, which are now preserved in the Bvlgari Genta Art Collection in Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Hailing from the Mecca of watchmaking led to his artistry taking the shape of Swiss watches. Soon, he collaborated with brands such as Universal Genève and Omega. His larger-than-life character and artistic ego allowed him the freedom to redesign and revitalize any brand’s existing models, breaking a lineage of tradition and complacency. This approach had its ups and downs but was interesting enough to catch the attention of higher-end brands. His emergence could not have come at a better time. As Genta was realizing his potential, the mechanical watch industry was marching towards a war it would not emerge from unscathed. The Quartz Crisis threatened everything. The industry’s best hope of survival was in embracing the genius of a local boy who seemed able to breathe new life into anything he touched.

The Audemars Piguet Royal Oak was born 50 years ago

One such brand was Audemars Piguet. As the story goes, AP contacted Genta with a rather far-reaching request. The remit? To conceive a new watch-design language. The timeframe? The next working day. Genta duly accepted and sketched his ideas overnight. Audemars Piguet presented Genta’s work to its investors. Although one could well imagine a confused response to the avant-garde proposal, the results sufficiently impressed the investors, and they signed off on the design. As you may have already guessed, this overnight epiphany came to be known as the Royal Oak (after narrowly escaping being named the Audemars Piguet Safari). This took place a whole 50 years ago, and AP is currently celebrating with a number of special releases.

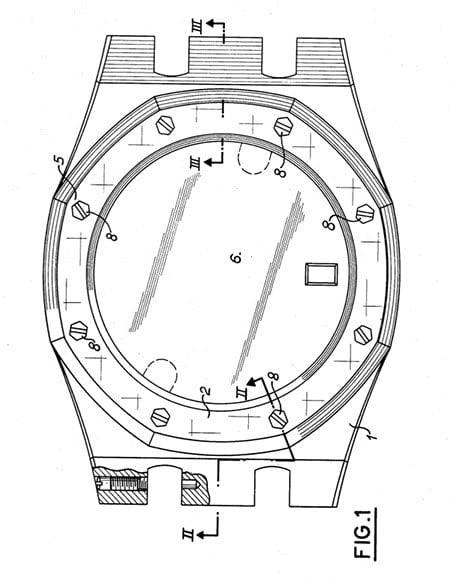

Core to the concept was the seamless link between the bracelet and the case of the watch. On most watches, the protruding lugs provided a clear delineation between the case and the bracelet or strap. The Royal Oak, however, was vastly different, with the case and bracelet taking on a cuff-like appearance. Now, it must be said that Genta did not invent the integrated bracelet. That honor, in fact, went to Omega’s Pierre Moinat in 1964. Nevertheless, the unified design gave the Royal Oak its fluid appearance, and many consider its bracelet one of the all-time greats.

Step into the octagon

One of the most recognizable aspects of the design is the octagonal bezel. While many believe it was inspired by a ship’s porthole, Genta stumbled across the idea when observing a diver’s helmet. He was taken by the raw functionality of the exposed screw heads and decided to incorporate the idea into his design. It turned out to be yet another flash of brilliance. In luxury watches (especially up until that point), designers attempted to achieve the appearance of flawlessness. Watches had to look like they had come into existence without the need for human intervention. By celebrating something as functional as a screw (or, as in the case of the AP Royal Oak, a bolt) Genta kicked down the door that led to the subsequent generations of experimental design.

While many assume that the bolts are non-functional (as the general assumption is that they are screws rather than bolts held in place by corresponding nuts tightened from the underside). The genuine functionality of this design element sends a message — that the process is to be as celebrated as the result. The only design flourish is the positioning of the grooves, which correlate with the lines of the octagonal case. The bolts themselves were made from white gold. This is because steel could not be precisely machined to the correct scale with the techniques of the time.

Reaching iconic status

While the success of Audemars Piguet today is undeniable, back in 1972, the Royal Oak was not a clear-cut hit. The market was not ready for a luxury sports watch in stainless steel that was priced and treated like gold. It was priced sometimes ahead of the brand’s gold pieces and four times more than a Rolex Submariner of the time. This carries over somewhat into today’s market too. It’s an adage that designs can sometimes be “ahead of their time”, but in the case of the Royal Oak, it rings true. Genta’s singular vision was to conceive styles that exude luxury despite the utilitarian material of stainless steel. Fifty years later, the watch’s iconic status speaks for itself.

The Patek Philippe Nautilus is born

From there, the Royal Oak gathered steam with more marketing investment brought in by a young Jean-Claude Biver. In Basel, during the annual watch fair, Genta was enjoying a quiet dinner in a hotel restaurant when he spotted some Patek Philippe executives wining and dining. He requested a pencil and paper from the waiter. In just five minutes, he sketched a new concept that would suit Patek’s lineup. His thinking was to soften the sharp edges of the Royal Oak. The idea was to offer a less masculine watch, more suitable for ladies’ wrists. He shared his designs with Patek, who did not immediately embrace the look. However, the brand did see potential in allowing the watch to be enjoyed equally by both genders.

This notion went on to become the Patek Philippe Nautilus. Given the timing of Genta’s approach, the idea that Patek imitated the Royal Oak concept hoping to piggyback on its success does not check out, as Audemars Piguet were far from seeing a solid return on their investment in the radical release. Rather, it is thanks to Genta’s singular vision and indomitable self-belief that the Nautilus followed the Royal Oak into production.

Patek Philippe’s Nautilus carried over the nautical themes seen in the Royal Oak but significantly streamlined the design. An unusual hinged case (resulting in the iconic “ears” of the Nautilus) set the design apart from its peers. As with the Royal Oak, Genta was keen to blend the industrial with the divine. Thus, he left the screws exposed on the sides of the bracelet, juxtaposing with the luxurious surface finishing of the bracelet and bezel, and the moody, maritime-inspired dial. Forty-six years since its release in 1976, the Nautilus remains one of the most sought-after models the industry has ever seen.

The legend continues

With these two designs, Gérald Genta created tremendous value for the associated brands, but he did not care for the commercial aspect. Genta designed watches for himself as a medium for his art. He was as proud of his Timex designs as he was of any other creations. He ultimately established an eponymous brand in 1983, giving his exuberant designs the freedom for expression without limitations. Genta watches were successful during the ’80s and ’90s. So much so, in fact, that he was permitted to use Disney-licensed characters on the dials. Announcing these designs amongst his stoic contemporaries during Baselworld was certainly provocative. But that’s the kind of light-hearted approach that Genta reveled in. He was excited and felt liberated in his design freedom.

Not all of his compositions were hits. Later in his life, his watches became more ornate and baroque with excessive complications resulting in limited commercial appeal. With multiple creations under his belt, it is understandable that not all would be so well received. With this direction and Genta’s age, his eponymous brand was becoming less feasible financially and the production techniques, core values, and intellectual property were absorbed into Bvlgari. However, watches like the Octo Finissimo carry on his legacy by combining designs from Genta and Bvlgari.

Gérald Genta’s mark on the history of watchmaking is unmistakable. His rule-breaking attitude may very well have helped ensure the survival of Swiss mechanical watchmaking during the downturn of the ’70s to the late ’90s.

Read more about Gérald Genta’s brand here, and let us know your all-time favorite Genta design in the comments below.

Follow me on Instagram @benjameshodges