Rolex Watches For WWII POWs And The Great Escape

World War II wreaked havoc around the globe. Many millions died, and at times, it must have felt like the end of the world as nations committed everything to defeating their enemies. Rolex also lent a hand in a small way by providing timepieces to prisoners of war (POWs).

As a graduate history student, I have always had a deep interest in this period. And as a journalist who, in my day job, has worked in conflict zones, something about WWII as a subject has always drawn me in. I think it’s because I hope that by studying that period, we can all take stock of the true human cost of conflict.

Rolex and WWII

This isn’t the first story about Rolex and WWII that I’ve written on Fratello. I’ve looked at how an Australian soldier with the Rats of Tobruk fought against the Axis in North Africa with a Rolex strapped to his wrist. A local collector here in Australia later found this watch and even managed to track down images of the soldier (and watch) in action.

I wrote another story about the role that Rolex and early Tudor watches played on the wrists of many Royal Canadian Navy officers during the Battle of the Atlantic. This included tracking down some incredible historical images. But what follows is a story about Rolex and POWs in particular.

Rolex and POW watches

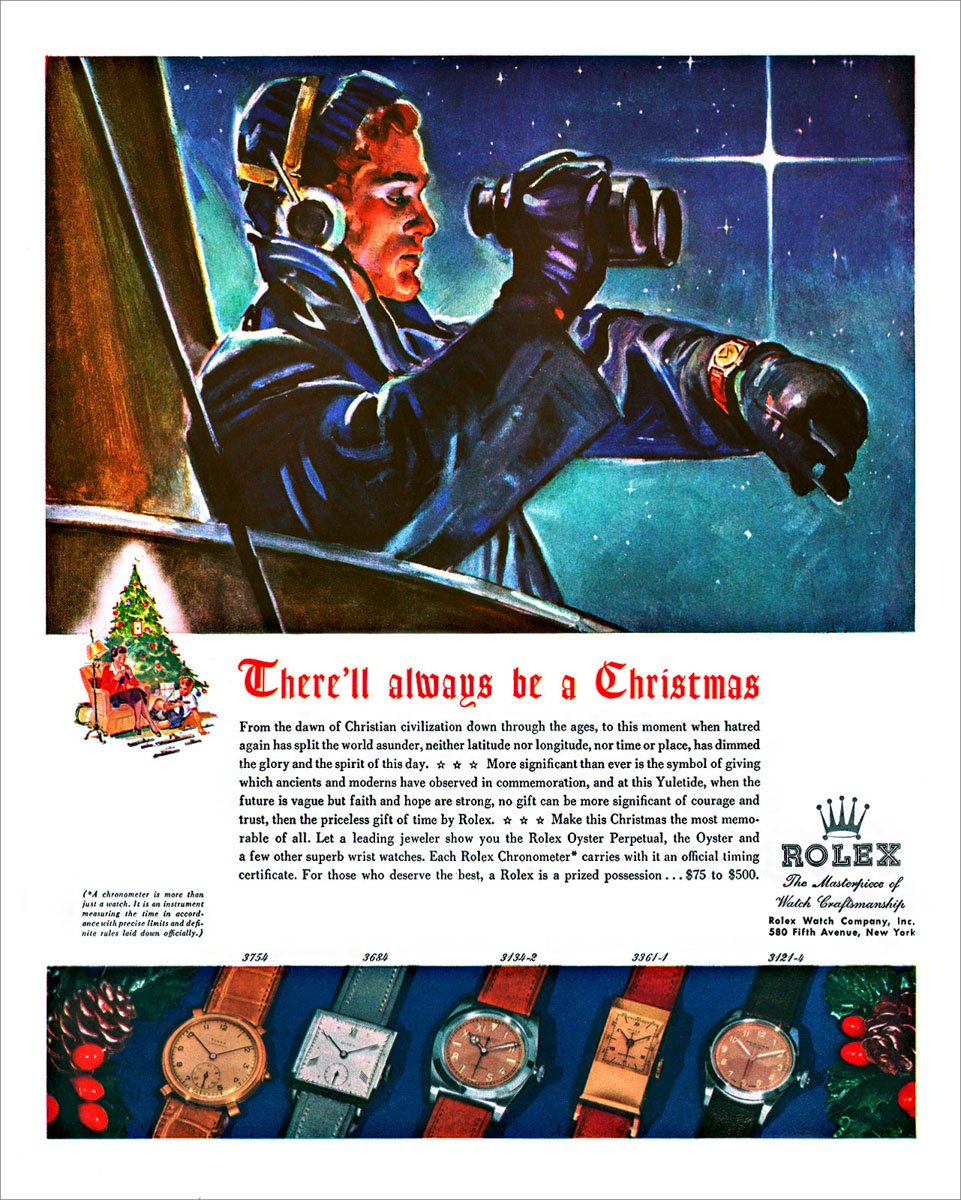

For soldiers who faced internment in a prisoner-of-war camp during WWII, things must have seemed particularly grim. In a stroke of marketing genius, however, Hans Wilsdorf of Rolex decided to provide Allied POWs with watches from his company.

A grim conflict

Why not let prisoners purchase new watches on the proviso that they could pay for them postwar upon their release? The notion served multiple purposes. Not only did it act as a morale boost for the POWs, but it was also a good way to raise Rolex’s profile.

In this wonderful article by Rolex Magazine, we can see the personal story of one such POW, Clive James Nutting. For those interested in the story of one Allied POW soldier and his Rolex, please read it. And, as Watches of Espionage noted, this move could not have come at a more appropriate time. The scale of human misery in WWII made every human conflict up to that point simply pale in comparison.

Neutral Switzerland provides an opportunity for Rolex

Now, the logistics for Rolex to deliver watches to Allied POWs in Germany were possible because of Switzerland’s neutrality in the conflict. As I have reported here on Fratello before, though, even if Switzerland was neutral, it still faced accidental bombing by Allied air forces as well as the constant threat of a German invasion. In fact, Nazi Germany had drawn up plans to invade Switzerland but never carried them out.

Packages could be sent from Switzerland to camps inside Germany. Even so, Wilsdorf was taking a risk because there was no way to guarantee that the POWs could pay him back at the end of the war. No one knew who would win WWII (except perhaps in the very late stages of the conflict) or even when it would end. Wilsdorf must have realized there was a chance he would have to write every single watch off.

Thousands of Rolex watches delivered to POWs

Interestingly enough, according to sources like Rolex Magazine, British POW officers ordered as many as 3,000 Rolex watches. Wilsdorf’s decision to let the Allied soldiers sort out payment after the war implies that he believed that the Axis (Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan) would lose, and this certainly would have raised morale among the Allied POWs when receiving their watches. Imagine the feeling of getting a brand-new Rolex watch while stuck in an internment camp. It must have felt wonderful.

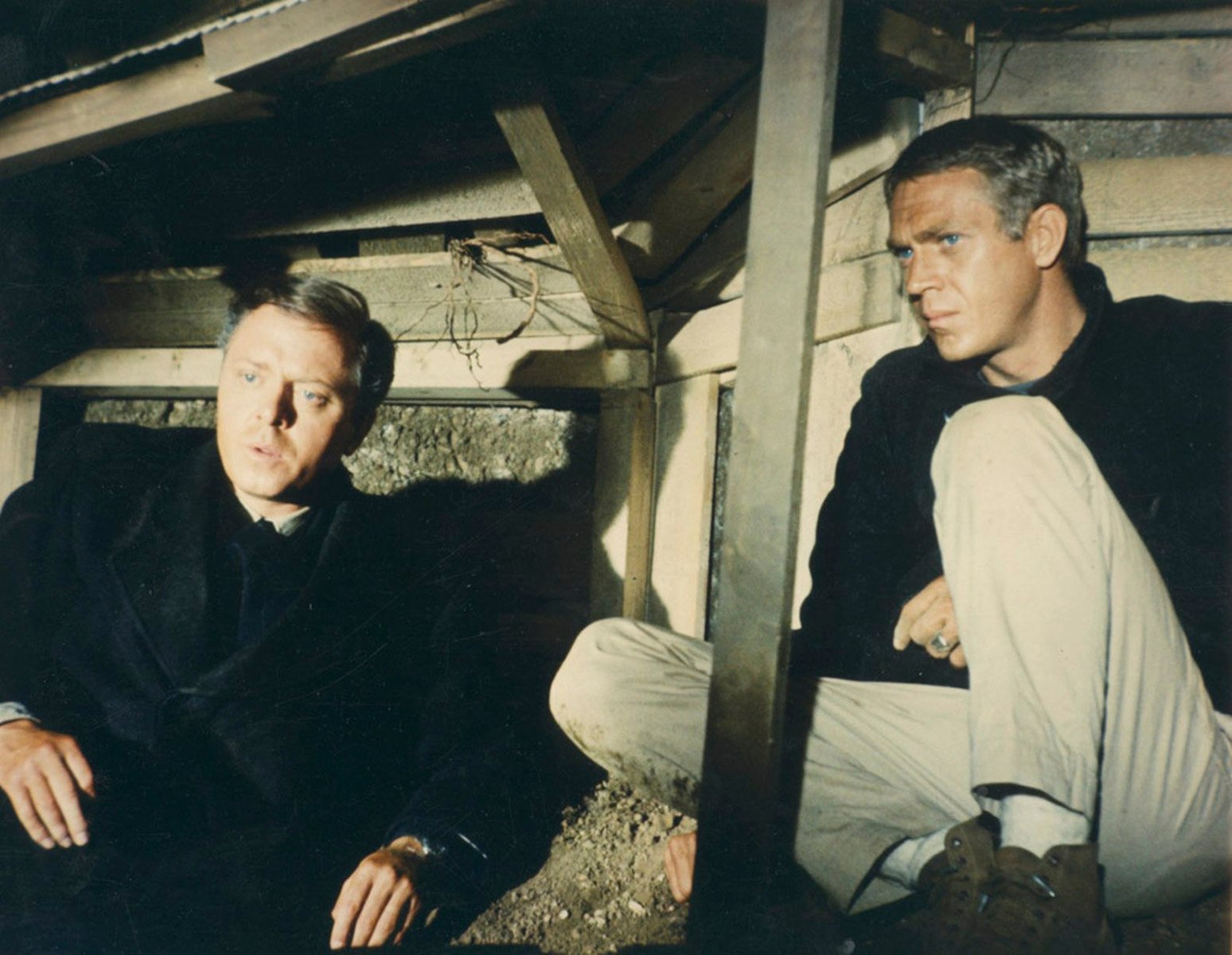

It also turns out that some of those Allied POWs who took part in what became immortalized as The Great Escape were wearing Rolex POW watches. This escape consisted of 76 Allied airmen from Stalag Luft III Nazi Luftwaffe Prisoner of War camp in March 1944. It has since become one of history’s most famous prison breaks and was the subject of the 1963 film The Great Escape.

Rolex watches and The Great Escape

Stalag Luft III was 100 miles southeast of Berlin. The historical escape is incredible when you consider the lengths to which prison security went to keep prisoners inside. These included raising prisoners’ huts about two feet off the ground to prevent tunneling from within and burying microphones 8–10 feet underground along the perimeter fencing to pick up any sounds of digging. The Germans had purposely built the camp on top of a sand base that made tunneling dangerous and unstable. It also made it harder for prisoners to conceal when they were digging.

According to historical accounts and modern estimations, POWs must have excavated more than 100 tons of sand to prepare for their escape. They hid it (just like in a scene in the 1963 movie) by raking the sand into the prison gardens.

The moment to escape comes

The escape was orchestrated by Roger Bushell, a Royal Air Force pilot who had been shot down over France while assisting with the Allied evacuation of Dunkirk. Bushell and as many as 600 fellow prisoners started building three tunnels (with the code names Harry, Dick, and Tom) which would stretch to about 300 feet, which was the distance to forest cover outside the camp fenceline. The penalty for being found outside the camp could be death, so they were all taking huge risks. However, the POWs reasoned that if they could reach the forest, they might just stand a chance. To avoid the microphones, they dug to a depth of around 30 feet. They used a trap door concealed beneath a stove which was always kept lit to discourage their guards from looking underneath.

According to historical records, “Prisoners stripped some 4,000 wooden bed boards to build ladders and shore up the sandy walls of the two-foot-wide tunnels to prevent their collapse. They stuffed 1,700 blankets against the walls to muffle sounds. They converted more than 1,400 powdered milk tin cans provided by the Red Cross into digging tools and lamps in which wicks fashioned from pajama cords were burned in mutton fat skimmed off the greasy soup they were served.”

The end of the “Harry” tunnel, which shows how close the exit was to the camp fence — Image: Wikipedia

The hunt for the escapees

After the 76 prisoners escaped, the manhunt was enormous. Within two weeks, the Germans had recaptured 73 of them. Three ended up successfully fleeing. Two were Norwegians who stowed away on a Swedish freighter, and one was a Dutchman who made it to Gibraltar. Adolf Hitler personally ordered the execution of 50 of the escapees.

Among those who planned to escape was RAF Corporal Clive James Nutting. According to this article by Rolex Magazine, Nutting’s stainless steel Rolex Oyster Chronograph ref. 3525 was delivered to the camp on August 4th, 1943. The construction of the tunnels had already been underway for at least five months by this stage. The Rolex Magazine story notes that Nutting wrote to Rolex seeking his final invoice in 1948.

Concluding thoughts

Nutting was unable to use the tunnel before it was discovered, a sequence of events that most likely saved his life. He ended up moving to my home country of Australia with his family in the early 1970s. His watch and associated correspondence with Hans Wilsdorf were sold at auction by Antiquorum for £66,000 in 2007. Nutting went on to work as a consultant for the 1950 film The Wooden Horse and, over a decade later, The Great Escape. Other POW Rolex watches have also come up for auction in the past.

On behalf of Fratello, I’d like to thank the countless servicemen and servicewomen who served in that global conflict. The powerful stories that came from it continue to resonate with younger generations today.