Studying The Rado Captain Cook Dive Watch In Bronze

The Rado Captain Cook family first appeared in 1962. It disappeared not long after in 1968. For almost fifty years the Rado Captain Cook collection lay dormant. That was until 2017 when the 37mm steel version was revived. It was joined also by a reimagined 45mm version in a hardened titanium case designed for a modern audience. Nowadays, we have the option of a much more versatile 42mm case to play with, but new for 2020 is the addition of bronze options to the line-up. Sure, it looks great, but there’s more to it than that…

When bronze first became a mainstream thing in luxury watchmaking, there was quite a pushback against it. In fact, despite this rugged material finding its groove in the industry, there are still a great many people that think it has no place in high-end horology. But there certain areas of the craft in which bronze feels more at home. There is an unavoidable thematic link between bronze and the ocean. As such, seeing it used on dive watches always seems a bit more comfortable than when it is applied elsewhere.

Highly resistant

Bronze’s link to seafaring originates in the material’s use for ship’s components due to its ability to withstand saltwater corrosion. Unlike brass, bronze contains little or no zinc and is much better for seawater applications. I say “little or no zinc”, but that is only because there is one type of brass (defined as such by the zinc within it) known as “manganese bronze”. Technically speaking, the fact it has zinc in it means it isn’t really bronze at all and is, in fact, brass. I just thought I’d make that distinction in case anybody has heard (and knows the composition) of manganese bronze.

Brass and bronze

Brass itself is perhaps even more often associated with the sea because it was used for a lot of the more aesthetic fittings one might find about a ship. Bronze, however, is preferred when the components in question come into contact with water. And just as there are many types of brass alloys comprising varying levels of copper and zinc, with other additives like aluminum, manganese, nickel, iron, and even lead changing the end product and its suitability for certain applications.

Typically, bronze alloys comprise a high level of copper…

Bronze can look quite similar to brass but is generally redder due to its higher copper content. That isn’t exclusively true, however, as some aluminum bronzes can be quite pale in comparison to their darker brethren. These are far easier to mistake for bronze. Typically, bronze alloys comprise a high level of copper (close to 90%) and tin. There are other types of bronze that contain things like zinc, manganese, aluminum, nickel, phosphorus, silicon, and, bizarrely, even arsenic…

Different types of bronze

To complicate matters slightly, there are multiple types of bronze used in watchmaking. Perhaps the most common is aluminum bronze (CuAl), of which there are many types also. Aluminum bronze is popular for its brighter hue and aesthetically pleasing patina, while CuSn8 and CuSn6 bronzes are favored by more technical pieces due to their higher resistance to saltwater corrosion.

So what’s the difference? Both CuSn8 and CuSn6 bronzes use a majority copper content with a minority tin component (the rough percentage of which represented by the “8” and the “6”), as well as a dash (0.1-0.4%) of phosphor thrown into the mix. These marine-grade alloys are often used for the production of essential shipping components such as propellers. They tend to take on a really deep, greenish hue over time (verdigris). Verdigris differs from bronze disease (which, admittedly, does look quite similar at stages to the untrained eye) in that verdigris actually protects the metal from corrosion (in the same way the oxidized blue of a heat-treated screw protects the underlying carbon steel from rust), while bronze disease is eating away at the base material itself. That’s bad, in case you were wondering…

…manufacturing with CuSn8 and CuSn6 is considerably more expensive…

Of these two bronzes, CuSn8 is preferred because its higher tin content makes it even more resistant. However, manufacturing with CuSn8 and CuSn6 is considerably more expensive and comes with aesthetic implications that some manufacturers, including Rado in the case of the CuAl Captain Cook dive watch, see as undesirable.

Brighter is better

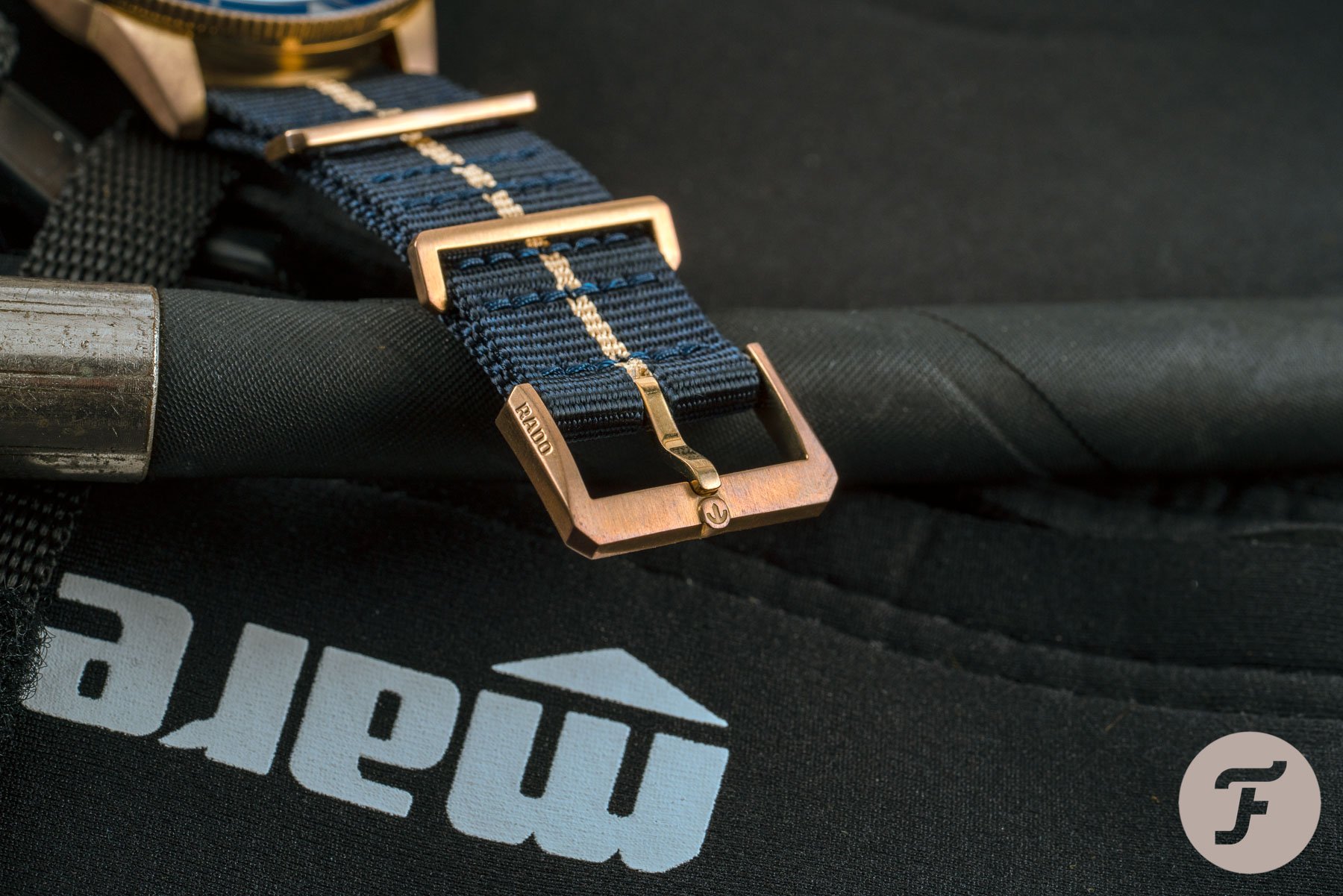

Aluminum bronze replaces the tin content with aluminum. This changes the appearance of the bronze significantly, making it lighter and more golden in color. The wear resistance of aluminum bronze is still very good, but it is far more cost-effective to produce. Also — although this is a matter of taste — its patina notably differs from tin-rich copper alloys. It tends (depending on the Ph level of your own skin) to go a reddish-brown color rather than the murky green or deep-brown of its tin-rich alternatives.

The Captain Cook debuted as a contemporary, functional dive watch in the glorious golden age of seafaring timepieces. This modern reimagining is the jewel in the Rado catalog. As such, it makes sense to me that the brand opted for the brighter, more golden tones of CuAl. I wear a lot of diving watches and own one or two bronze pieces. The difference in the way my CuSn8 and CuAl pieces age is apparent.

…CuAl takes on an altogether more vibrant hue.

After a while, CuSn8 looks like it has more in common with the Antikythera mechanism than modern watchmaking. Meanwhile, CuAl takes on an altogether more vibrant hue. Some will prefer the dull, ruggedness of CuSn8. Some will fawn over the flashier CuAl. I think there’s a place for both in anyone’s collection.

Patinas are cool

Watching your watch patina is great fun. It’s even possible to force your watch to patina faster and in different ways. Our very own Bert tried it himself, with pretty interesting results. I’ve even stripped back the patina on my CuSn8 watch myself, but I must admit I instantly regretted it. I immediately missed the stories behind the origin of the watch’s original patina. It reminded me of all the things I’d seen and done with that watch on my wrist. It made me feel ridiculous. I’d never expected to have such an emotional reaction to the removal of something that I had before seen as nothing more than, well, dirt…

…let it age naturally and gracefully with you.

Since stripping my own, hard-earned patina, I’ve taken pains to put that watch through its paces. It has started accompanying me on runs, in the pool, in the ocean, and in basically any environment that might encourage a reaction. The results are different from the first time around, but I am starting to love it again. My advice to anyone that buys a Rado Captain Cook in bronze is to let it age naturally and gracefully with you.

Messing with patinas is more interesting than it is fun. Sometimes, it can be downright stressful. Occasionally, it could be devastating (as my own experience turned out to be). Instead, wear it, enjoy it, and heck, even dive with it! The presence of a nicely-lumed ceramic bezel insert (the bezel numbers glow blue while the dial markers glow green) makes that even more enjoyable! That’s what it was designed for and it’s never looked more at home beneath the waves as it does in its modern CuAl skin. Caps off to the Captain — a timely and contemporary update for a watch that was certainly ready for it. Learn more about Rado here.