The Olympian IWC Watch Designer Who Fought Nazis In The Skies Of Switzerland

This feature was researched with the help of Nic Barnes, who is a pilot, watch enthusiast, and occasional contributor for Watches of Espionage. Our thanks to the Schaffhausen City Archive and Schaffhauser Magazine for providing materials that greatly contributed to our research for this story. It is one about a remarkable man with connections to IWC Schaffhausen who took part in a significant air battle over Switzerland in June 1940.

This is a story about air battles over Switzerland at a moment when Nazi Germany seemed unbeatable. We will get to that tale shortly, but first, allow me to provide some context. Many of you may know that I have a soft spot for IWC Schaffhausen. A member of my family was killed in the US bombing of Schaffhausen on April 1st, 1944. The incident heavily damaged many parts of the town, killing dozens. My grandfather also grew up in Schaffhausen before moving to New Zealand, and he was the proud owner of a few IWC watches, including this IWC Cal. 89. This is a caliber with a fascinating history.

IWC’s aviation tradition

Caliber 89 was developed as a movement for the IWC Mark 11, a navigator’s watch for the British Ministry of Defence (MoD). It was a successor of the Mark X, which was produced during WWII. As many readers already know, pilot’s watches are an integral part of IWC Schaffhausen’s DNA. The Mark and Big Pilot series of watches serve as pillars of the brand’s modern collections. These models stem from the watchmaker’s long record of producing pilot’s watches for military forces.

Much has been written about this history, (here is an excellent article by my colleague Thomas on the subject), particularly the use of the Mark series by various armed forces and civil organizations. This is a tradition of sorts that continues to this day, including with the Royal Australian Air Force. Today, we look into one chapter that, while less known, is no less remarkable. It concerns the ancestor of the IWC Mark X and 11, the 1936 IWC Spezialuhr für Flieger.

The 1936 IWC Spezialuhr für Flieger — Photo: IWC

IWC Schaffhausen and the pilot’s watch

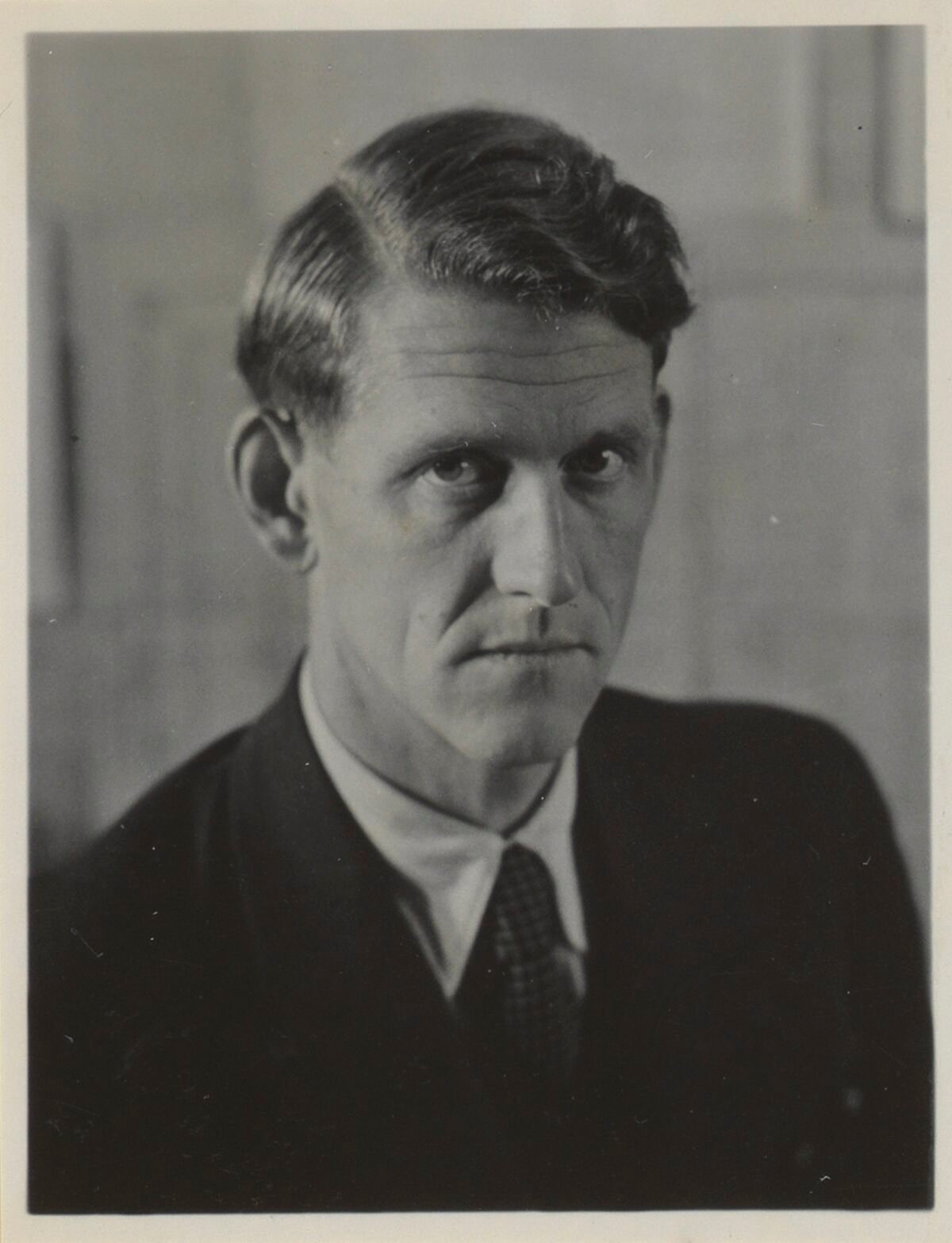

IWC’s first-ever pilot’s watch, the 1936 Spezialuhr für Flieger, was reportedly developed based on the experience of two sons of the then-owner of IWC, Ernst Homberger. These sons, Hans Ernst and Rudolf Homberger, were both pilots. They completed their civil pilot training in England in the early 1930s and were also successful athletes.

The 1936 IWC Spezialuhr für Flieger was a specialized pilot’s watch through and through. With a highly legible dial, it was focused on the demanding environments of flight. The technical features to meet these demanding conditions included an antimagnetic escapement and shatterproof front glass. The watch was also required to work at temperatures between -40° and +40° Celsius. This was considered an essential feature as aircraft cockpits were unheated at the time. IWC would also go on to develop the 1940 reference 431 “B-Uhr.” But while the influence of the two Homberger brothers on IWC’s commitment to pilot’s watches is noteworthy, the backstory of Ruedi’s aviation experiences is more remarkable. This is not a story about those early IWC pilot’s watches but about the man himself. Read on.

Early life and a connection to IWC Schaffhausen

Born in the Swiss town of Schaffhausen in 1910, Ruedi was the middle of three brothers and would spend his childhood vacation time in IWC’s precision engineering workshop. He graduated from university as a mechanical engineer, but besides engineering and technology, his other great love was sport.

Ruedi would go on to represent Switzerland in the men’s eight rowing event along with his brothers at the infamous 1936 Berlin Olympic Games. He was so horrified at Hitler’s Opening Ceremony address that he expressed a desire to immediately return home. The following year, Ruedi completed his military flying training and earned his Swiss Air Force wings.

Dark days across Europe as Nazism grows in strength

In the summer of 1940, the people of Switzerland were on edge. WWII had erupted, and the European superpowers of France, Great Britain, and Nazi Germany were in a vicious struggle (Italy would go on to declare war on the Allies and side with Nazi Germany on June 10th, 1940). By early June, it was clear the Germans were winning. They’d swept Allied forces from Europe with France on the verge of surrender. Switzerland was a neutral nation surrounded by countries at war. Expectations abounded that Switzerland was next in line to be invaded by Nazi Germany and join a host of European nations already invaded, including Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Norway.

In fact, secret plans to enact this, code-named Operation Tannenbaum, had already been drawn up. Swiss Army units were on high alert, and the Swiss Air Force was responding to an ever-increasing number of incursions into Swiss airspace by Luftwaffe planes that were on their way to bomb French targets. On June 4th, 1940, Swiss Air Force Lieutenant Rudolf Rickenbacher was patrolling Swiss airspace in his Messerschmitt Bf 109 aircraft (ironically, manufactured in Germany) when he was attacked by Luftwaffe intruders. That day, Rickenbacher became the first Swiss officer killed in WWII.

The Swiss fighter pilots battling the Germans

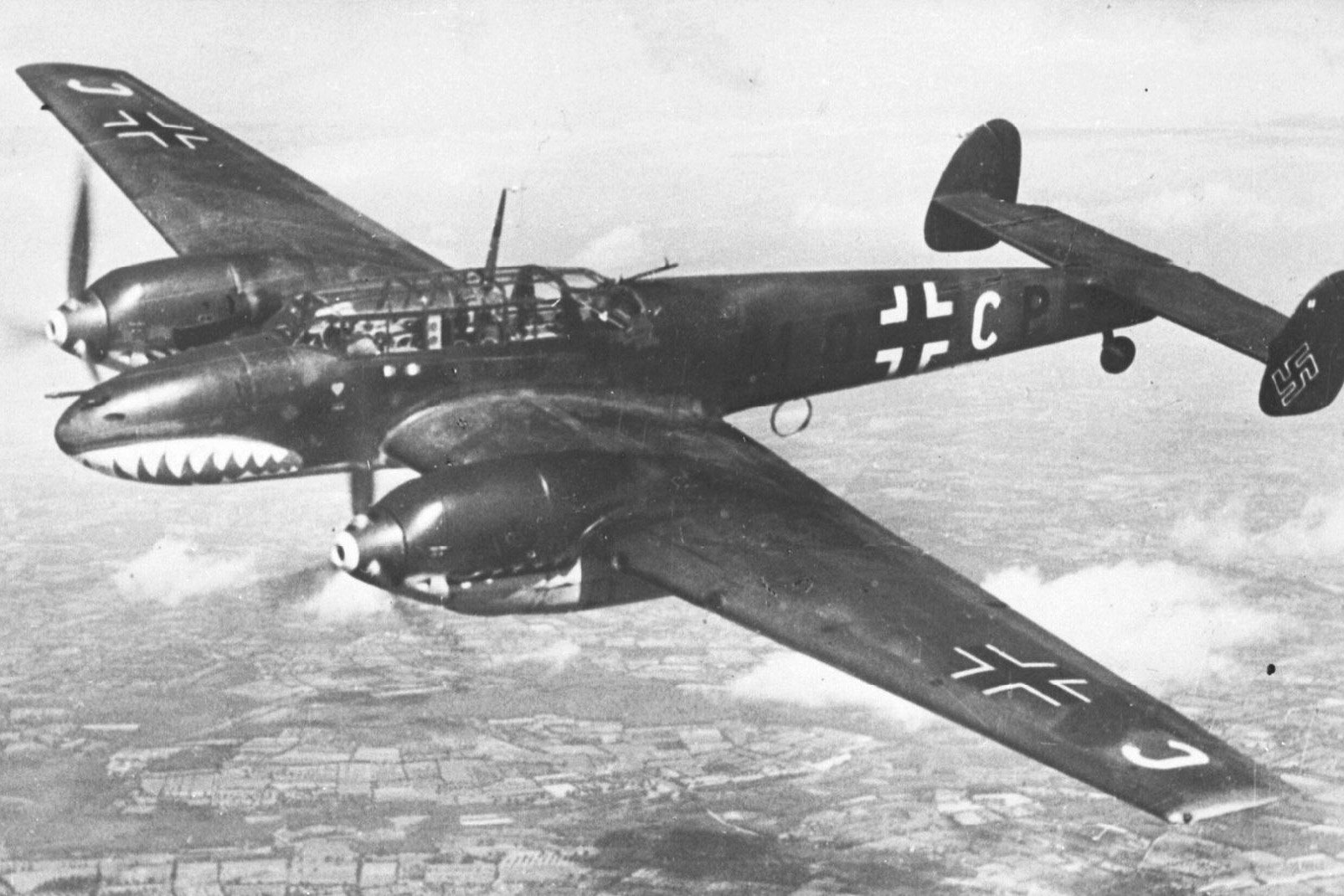

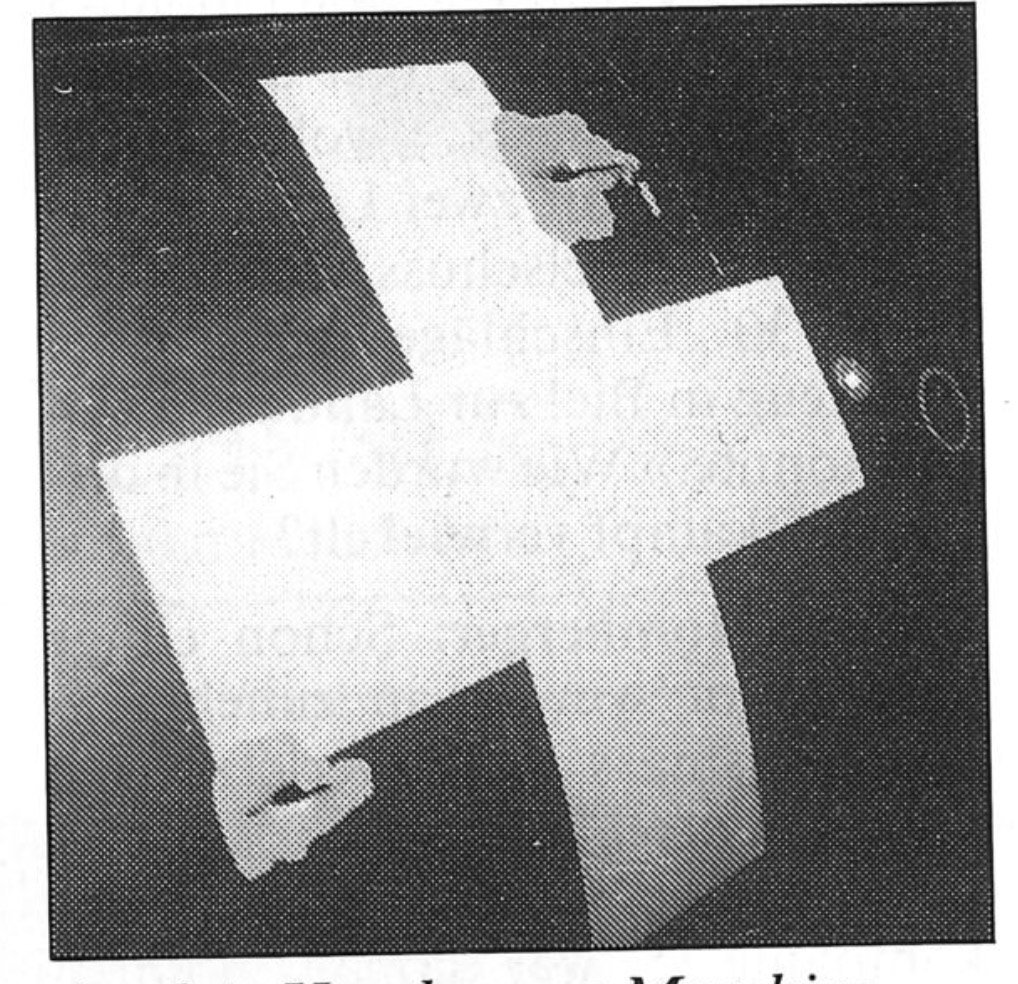

Later that week, on the morning of Saturday, June 8th, two more Swiss aircrew members were killed when their reconnaissance plane was ambushed by Luftwaffe fighters. By midday, the alarm was raised for members of the Fliegerstaffel 15 of the Swiss Air Force to scramble their fighter aircraft. One of the fighter pilots responding to the incursion was the young man from Schaffhausen, Ruedi Homberger. He was flying a German-made Messerschmitt Bf 109. These were the same fighter aircraft that went toe to toe with the Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes over the skies of Great Britain during the Battle of Britain. A few days earlier, there had already been a number of these incursions by Luftwaffe units inside Swiss airspace, so the Swiss pilots knew that they likely had a tough air battle on their hands.

On that day, the Swiss squadron was responding to a number of twin-engine Luftwaffe heavy fighters, Messerschmitt Bf 110s, that had strayed deep inside Swiss territory. The stakes were high, and dogfights would often be a battle to the death. According to Swiss records, in June alone, there were numerous border violations by German aircraft. “Around 30 pilots were involved in the defensive actions of the Swiss Air Force. A number of them returned to their bases with more or less damaged aircraft. But three pilots lost their lives in the air battles; one was able to make an emergency landing with serious injuries.”

Deadly dogfights in air battles over Switzerland

Ruedi Homberger and his fellow wingman Lieutenant Kuhn revved up the powerful Daimler-Benz engines in their Bf 109s, and the two of them took off from Payerne Air Base near Bern. Earlier that morning, a Swiss observation aircraft, a C-35 of Fl.Kp.10, had been attacked by surprise and shot down by six German Me 110s. Both pilots, First Lieutenant Gürtler and Lieutenant Meuli, were killed, as Ruedi later recounted in a 1998 interview with Schaffhauser Magazine.

“Only the day before, we had buried our cameraman, Lt. Rickenbacher, who had been shot down and killed by the Germans over Boécourt on June 4,’ he said. “The Germans wanted to punish us because we refused to let them fly over our territory when they were returning home from their bombing missions in the Lyon area.” The timing of the scramble was unlucky for Homberger, who was due to go on vacation at 1:00 that afternoon. But there was no question about the importance of defending his homeland’s air space when the alarm sounded at midday.

A heavy fighter force

The Luftwaffe had sent a sizable fighter force to teach the small Swiss Air Force a lesson for earlier interceptions. Historians estimate that 22 to 25 heavy Luftwaffe fighters had formed an attack formation over the Jura mountains. They’d positioned themselves at different altitudes to support each other for the expected Swiss response. “The first patrol to take off was Lieutenant Hans Kuhn and I, followed by Captain Lindecker and Lieutenant Egli. Our mission was to prevent foreign aircraft from entering the country,” Homberger said.

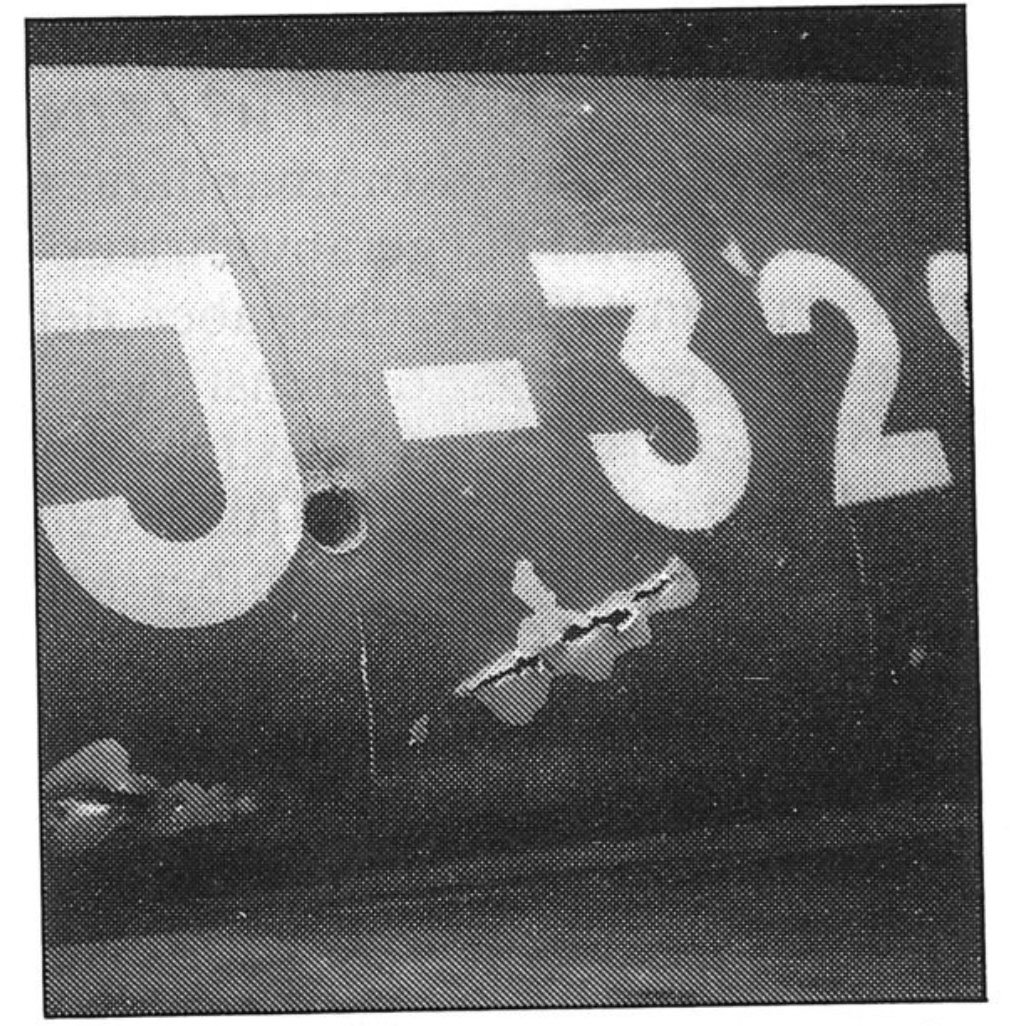

“Lt. Kuhn and I communicated by hand signals, as the radio usually didn’t work. We approached, spiraled higher, and tried to use a cumulus cloud as cover. After flying through it, a German (in a Me 110) wiped me off. Bullets scraped the sheet metal of my plane, and I also felt two blows to my back, but I carried on. By then, the second Me 110 was already attacking me, I saved myself near the ground; I wanted to shake off the pursuers at the height of the church towers. When the Germans had disappeared, I pulled up again but felt that something was wrong with me. I was sweating and freezing at the same time,” he recounted.

A lucky forced landing

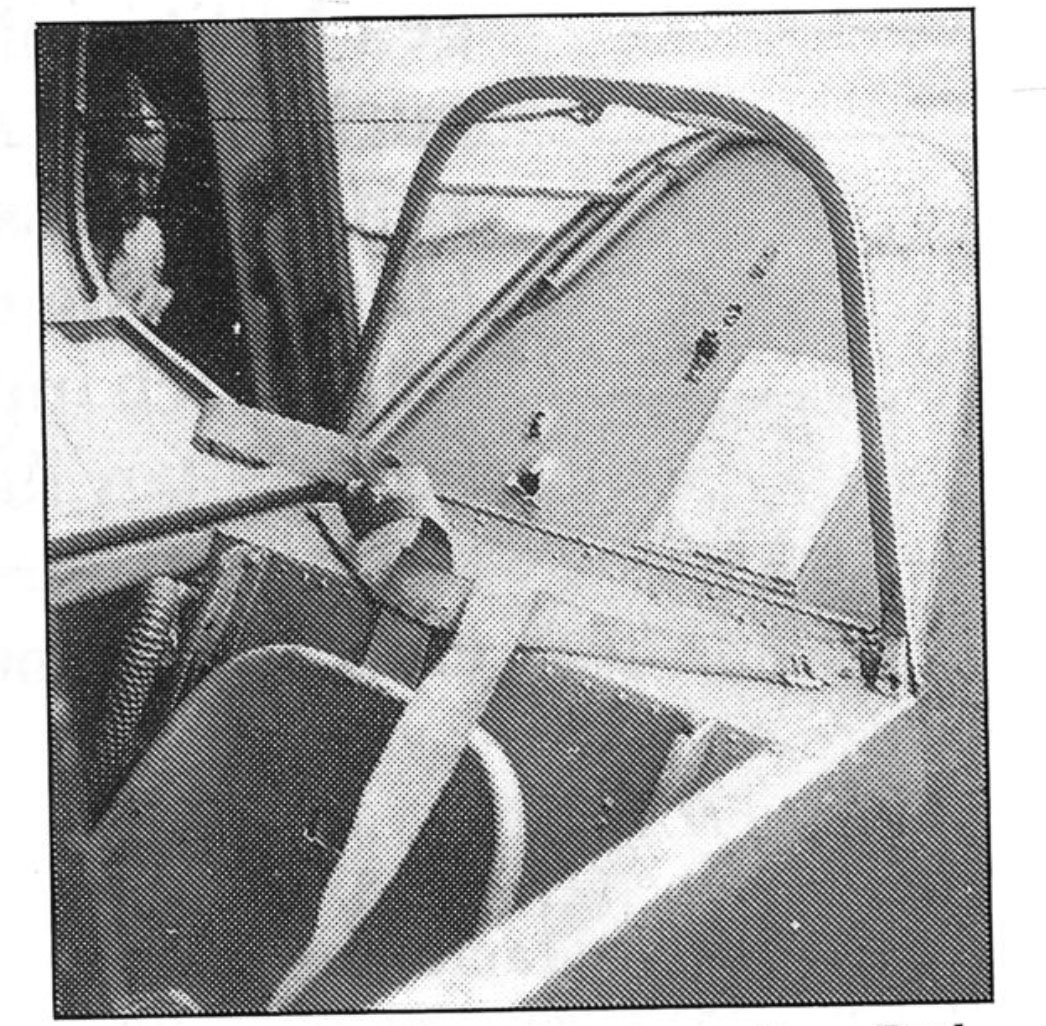

Homberger’s plane had been shot 34 times during the dogfight with the Luftwaffe formation. Two bullets had pierced his back and lung, and another had hit his thigh. He was flying on adrenaline. “I wanted to fly back but realized that it was obviously not going to be enough. So I flew to Bözingen and landed there. My vision narrowed more and more, [and] I could see almost nothing. Only the little fir tree planted as a landmark gave me a point of reference. I landed on one wheel and ground-looped because the other main wheel hadn’t locked due to a blown oil line. Then I lost consciousness,” he said.

Homberger’s wingman had seen the dogfight develop. “Lieutenant Kuhn had noticed what had happened to me and probably thought I had crashed to the ground. He rushed at the German who had shot me down and fired all his ammunition at him. The enemy turned into the valley near St. Imier, and Lt. Kuhn escaped in a daring maneuver through the Taubenloch Gorge. Naturally, the Germans did not dare to go there. In this way, my comrade saved himself from the superior firepower of the Me 110, which, as it later turned out, he had hit so badly that it had to make an emergency landing near Nunningen. After landing in Olten, he (Lt. Kuhn) reported the aerial combat and also informed my wife.”

Homberger wakes up

The blackout can’t have lasted long. When Homberger came to, he realized the plane had come to a standstill on one wing. “Because of the damage, the right landing gear couldn’t lock because of the oil leak, and so it buckled during the forced landing,” he said.

“I heard that the engine was still running and switched off the ignition. Comrades from Fliegerkompanie 13 who were on duty at the time ran over and wanted to help me get out of the cockpit. I remember that I had forgotten to unplug the radio lead in the canopy. My exit became a fall, but there were two men standing below who caught me. They laid me on the ground in the angle between the wing and the fuselage. I was still in a state of shock, but I could still see that gasoline was dripping from the fuselage. You can imagine how urgently I demanded to be taken away because of the fire hazard before I fainted again,” he recounted.

Serious injuries

One machine gun bullet was removed from Homberger’s thigh in the hospital, but the fragments of another penetrated his lungs. A third bullet that entered his back would stay in him for the rest of his life — reminders of a very close call indeed. It would take two years for Homberger to recover enough to report back to active duty. But in 1942, he would join his comrades in the air again to continue to patrol Switzerland’s skies.

Speaking of his experiences years later, Homberger said that the willingness of the Swiss Air Force to respond to Luftwaffe incursions displayed Swiss resolve. “I am still of the opinion today that we were able to convince the Germans of the unconditional will of our army and our nation to resist,” he said.

The battles continue and almost destroy IWC Schaffhausen

As WWII continued, it would not just be Luftwaffe aircraft that fell afoul of Switzerland’s air defenses. Allied planes would, on occasion, come under fire. Others would try to crash land in neutral Switzerland rather than Germany. This happened during air raids if their planes developed problems or were seriously damaged.

The cost for Swiss citizens was considerable, with accidental bombings by Allied forces leading to the deaths of civilians and maiming dozens more during the war. In one particularly notorious incident, Schaffhausen was bombed by US Air Force heavy bombers. The damage to the town was considerable, and my great-grandfather was among those killed. In the image above, we can see the town on fire after the 1944 bombing. A bomb landed in the IWC factory but did not explode.

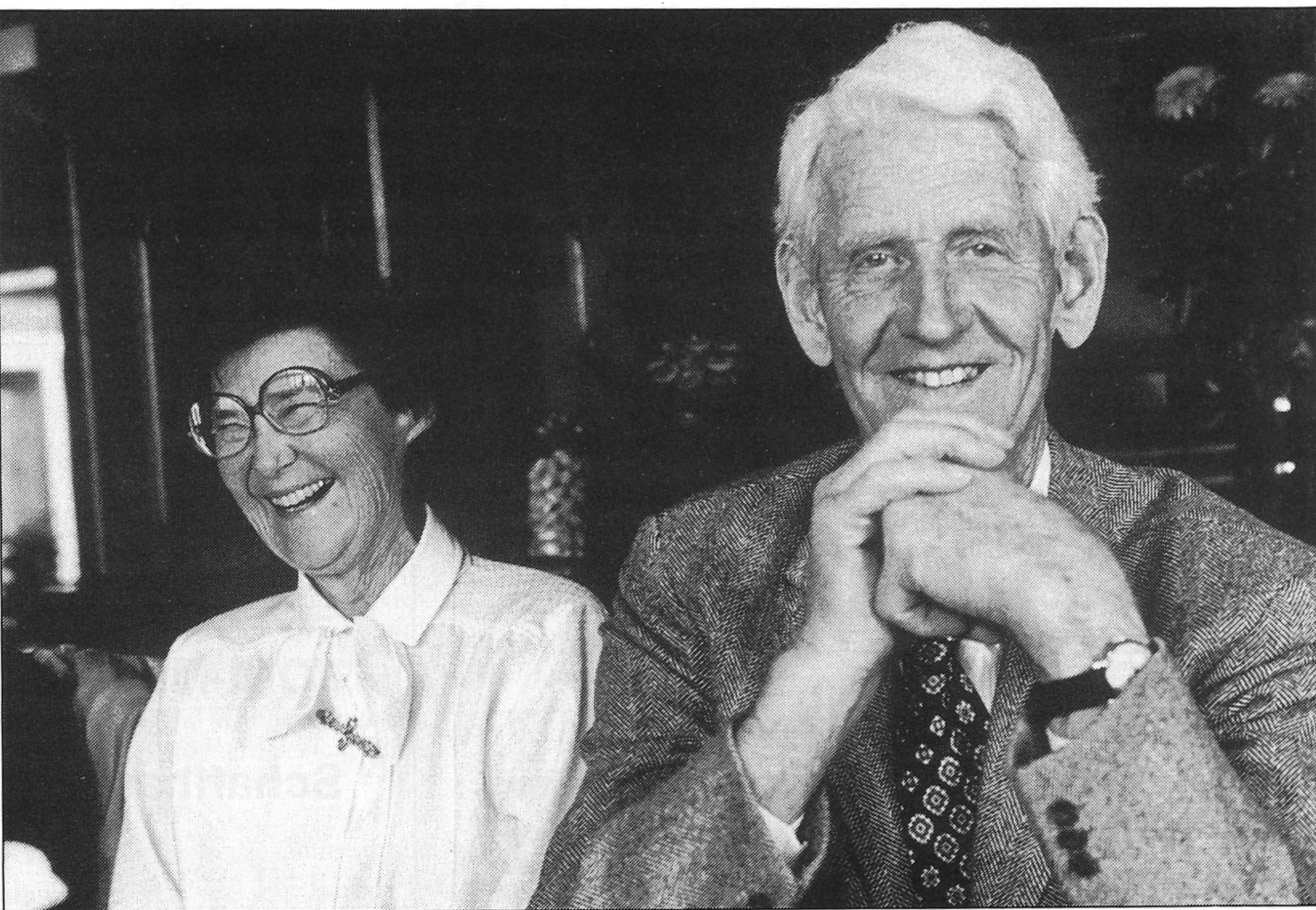

A life well lived and a lifelong connection to IWC

After the war, Ruedi Homberger resumed his work as an engineer at the Swiss industrial firm Georg Fischer. He passed away at the age of 89 in his hometown of Schaffhausen. His 1999 obituary noted he died “unexpectedly and as he had wished, namely without having to burden his family with illness.”

He was described as extraordinarily humble, valuing integrity above all other attributes. It is here that our story ends. I hope you enjoyed this remarkable little tale of air battles over Switzerland at the height of WWII. It shows that IWC Schaffhausen has genuine historical connections to pilot’s watches that run deeper than some may realize.