The Origins Of Hamilton Watch Company: The Early Years — 1892–1945

When I started my watch journey 16 years ago, Hamilton was a brand to which I instantly felt connected. There’s no doubt in my mind that was thanks to my grandfather, who was a lifelong enthusiast of the American railroad. He was an honorary member of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, and he had an unrelenting passion for trains and anything related to them. His entire Cleveland basement was filled with locomotive memorabilia, including lanterns, bells, signals, and, yes, watches. Though he collected many brands of American timepieces, Hamilton watches were his favorites by far. Even my grandmother, who knows and cares little about watches, can vouch for my grandfather’s love of the brand.

In my teens, I inherited one of my grandfather’s Hamilton pocket watches, which I foolishly neglected before moving to Japan. It still lives with my mother half the world away, and, these days, I’m aching to go back and wind it up again. But as silly as I was in not appreciating that treasure, my grandfather’s love of Hamilton watches greatly influenced my watch journey. At 18 years old, I bought my own Hamilton Khaki X-Wind, and it was the crowning piece in my collection for nearly ten years.

Currently, I’m studying more about watch brands than ever. As I’ve been digging into the history of Hamilton watches, I can clearly see why my grandfather loved them so much. The man lived and breathed the American railroad, and for so many years, Hamilton did as well. Today, we’ll take our first look at Hamilton’s rich history. I hope you’ll find it as interesting as my grandfather and I have.

The birth of Hamilton

The Hamilton Watch Company was founded in 1892 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, USA. The brand rose like a phoenix from the ashes of several prior watch companies that had struggled to gain traction in the prior two decades. The Adams & Perry Watch Company, the Lancaster Watch Company, and the Keystone Standard Watch Company had all strived for success, inhabiting the same manufacturing facility built in Lancaster in 1875. But a lack of capital and the effects of mismanagement saw their untimely demise, with Keystone Standard finally going bankrupt in 1891. A group of Lancaster-based investors, however, would not settle for less than a high-quality watch manufacturer bringing life to their town. So in October of 1892, the group purchased the Keystone Standard brand and facilities, as well as the struggling Aurora Watch Company of Aurora, Illinois.

The group chose the name Hamilton as a tribute to the original owner of the site of Lancaster, as well as its first planner — Andrew Hamilton and his son James.

The group decided to merge the two watchmaking companies, transporting Aurora’s machinery all the way to Lancaster. Along with it came Henry Cain, the superintendent of the Aurora Watch Company, and former head of Keystone Standard just a few years prior. Cain had also been one of the main investors in the project, and he had plans to develop serious railroad-ready timepieces. The group chose the name Hamilton as a tribute to the original owner of the site of Lancaster, as well as its first planner — Andrew Hamilton and his son James. The group built a new wing onto the Keystone Standard watch factory to accommodate the machinery brought in from Aurora. Hamilton wasted no time in establishing a legacy of tried-and-true timepieces with an American spirit.

The first Hamilton pocket watches for the railroad industry

The late 1800s saw the burgeoning of the American railroad industry, and railroad workers required timepieces of exacting precision. In the times before digital and satellite time references, the accuracy of pocket watches was of the utmost importance. Conductors’ watches running fast or slow by merely a minute could spell collisions and death for a train’s trusting passengers. Hamilton dedicated itself to providing the best pocket watches that the American railroads had ever seen. For several decades, this pursuit was Hamilton’s bread and butter, and it all started in 1893 with the Grade No. 936 watch.

Henry Cain had designed the 18-size (44.86mm-diameter) movement, equipped with 17 jewels, a 42-hour power reserve, and a full-plate design. It was adjusted for accuracy in five positions and featured a lever-set system. This required the user to disengage a lever (usually under the crystal) to set the hands via the crown. As opposed to “pendant-set” (push-pull crown) types, lever-set watches were somewhat inconvenient, but they were much more difficult to accidentally un-set. Lever-set watches became a railroad standard between 1906 and 1908, but Hamilton’s standards were more than a decade ahead of the curve.

Hamilton produced the Grade No. 936 from 1893 to 1915, upgrading its escapement around 1906. Hamilton’s most popular 18-size movement, however, was the 21-jewel Grade No. 940, produced from 1898 to 1928. In that time, over 200,000 movements were produced. Hamilton manufactured numerous 18-size calibers, a dozen or so of which met the railroad standards of timekeeping.

A railroad staple

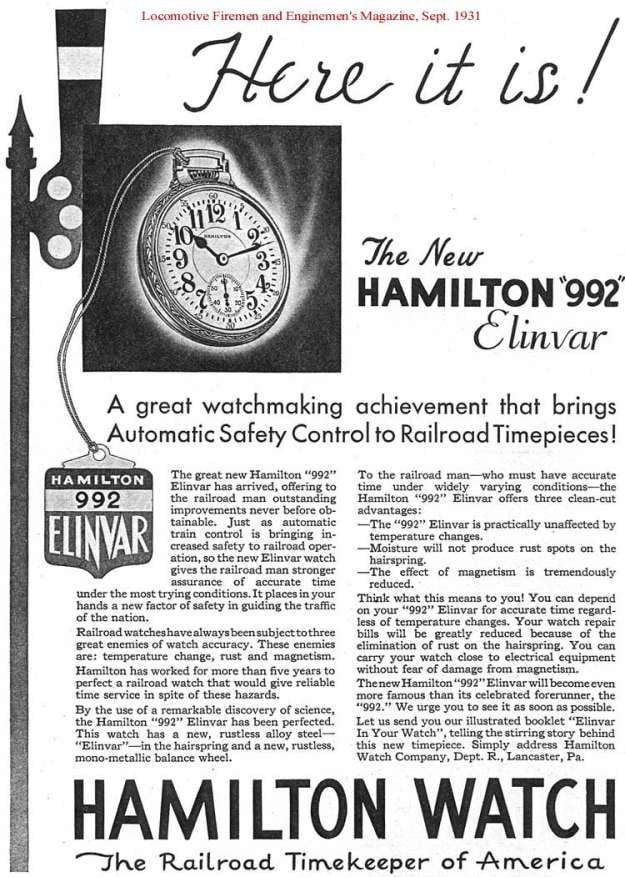

Around the turn of the century, the demand for slightly smaller 16-size movements (43.18mm-diameter) was also increasing. In 1896, Hamilton released its first 16-size caliber, Grade No. 960. This 21-jewel movement was originally pendant-set, but it received a lever-set upgrade in 1904. The Grade No. 992, however, as well as its later variation, would become the most popular Hamilton 16-size calibers by far. In production from 1903 to 1940, the Grade No. 992 saw a gradual increase in quality, including various upgrades to its escapement, hairspring, and balance. In its 37-year production run, Grade No. 992 would see a production of over 600,000 pieces, making it the most popular American railroad watch ever. Its successor, the Grade No. 992B, saw 525,000 pieces produced before its discontinuation in 1969.

There were dozens of Hamilton pocket watch movements, and the watches garnered a reputation as the best in the business. Just twenty years after the founding of Hamilton Watch Company, the brand had staked a serious claim in its chosen niche. In 1912, Hamilton proudly advertised, “Over half (almost 56%) of the Engineers, Conductors, and Trainmen on the railroads of America where official time inspection is maintained carry Hamilton Timekeepers.” The brand’s railroad watches were not only accurate and reliable but they provided supreme legibility as well. Most had beautiful white dials with stark, black Arabic numerals, and high-contrast hands for the best readability. Some even featured the so-called “Montgomery” dials, with both the hours and minutes labeled with Arabic numerals.

Not all of Hamilton’s pocket watches were railroad-approved, and some were built specifically for the general public. In its second decade in business, Hamilton began marketing to the everyday American citizens who simply wanted the best. The brand’s proven reputation for accuracy on the railroads played no small part in winning over the American public. But it also earned Hamilton the role of timepiece supplier to the American armed forces in 1914, as World War I began to throw civilization into disarray.

- Early Hamilton men’s wristwatch, circa 1917 — courtesy of Art Deco Wristwatches

- Hamilton 983 movement from the brand’s first men’s wristwatches, circa 1917 — courtesy of Art Deco Wristwatches

Early Hamilton wristwatches

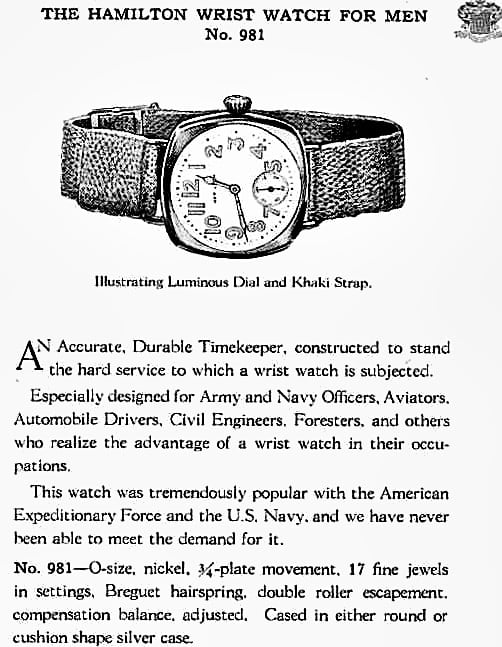

As early as 1912, Hamilton had produced “wristlets” for women using 0-size pendant watch movements. But as the dangers of battle rendered the pocket watch a liability, soldiers began modifying their watches to be worn on the wrist. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Hamilton responded to the demand for men’s wristwatches, producing pieces like the one seen above. These wristwatches, some of the first to see military use, were powered by the Hamilton caliber 983, a 17-jewel 0-size pendant movement.

In 1919, Hamilton began listing its men’s wristwatches in catalogs with the 981 caliber made exclusively for these models. Though many civilians at the time still saw wristwatches as feminine, the cool, masculine image of the soldiers who donned them even after returning home helped the concept catch on. Within a few years, wristwatches were here to stay.

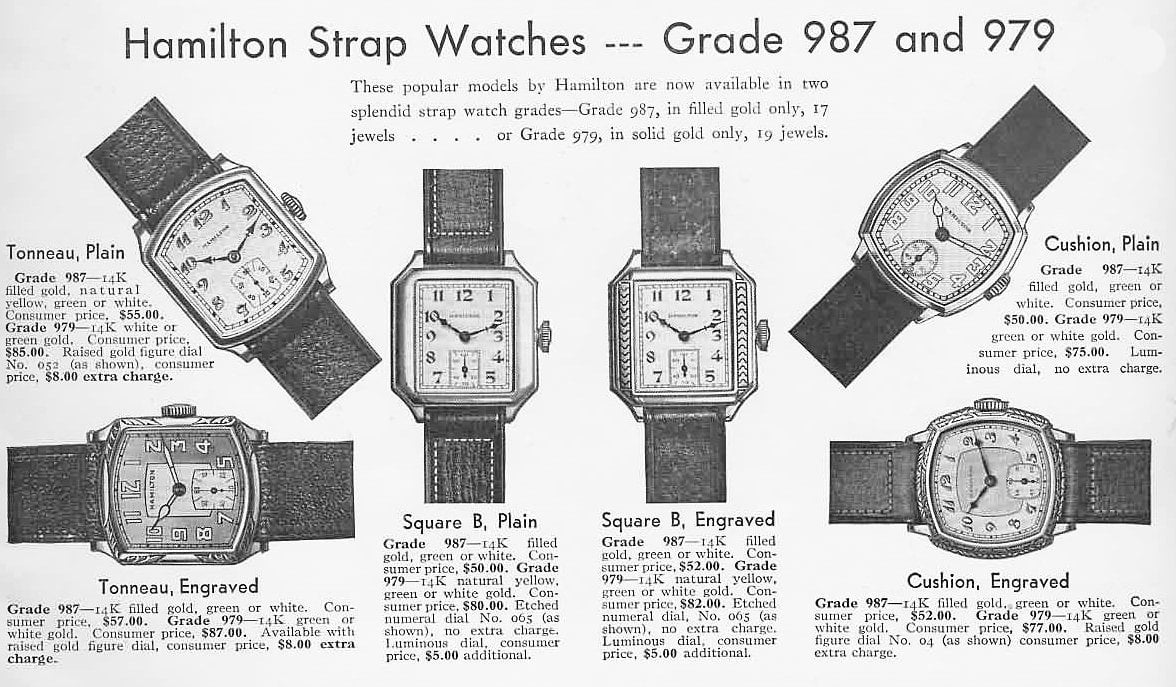

As the popularity of wristwatches continued to grow, Hamilton produced high-end ones like the pieces seen here. The 987 movement found in these wristwatches began its production run in 1924. Over the next 24 years, caliber 987 and its gradually evolving variants would power hundreds of thousands of Hamilton wristwatches, designed for both civilian and military use.

- 1918 Hamilton Advertisment — courtesy of Hamilton Chronicles

- Hamilton wristwatch with caliber 983, circa 1918 —courtesy of Hamilton Chronicles

Aviation and exploration

Backtracking a bit to 1918, the 26-year-old Hamilton company staked its claim in the skies. That year, Hamilton watches were on the wrists of the pilots who made the first U.S. Airmail run from Washington, D.C. to New York. It was the start of an over-century-long relationship between the Hamilton Watch Company and the aeronautics industry. Hamilton’s ties to aviation carry on to this day, and the brand’s pilot’s watches are a pillar of its modern collection. In 1926, a Hamilton watch accompanied Admiral Richard E. Byrd on his 15-hour-and-57-minute flight to the North Pole. Though there has been significant debate over whether Byrd actually reached the North Pole or not, Hamilton watches nevertheless served as valuable tools in Byrd’s other endeavors.

- Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s 1928 Hamilton watch

- Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s 1928 Hamilton watch

In 1928, Byrd set out on his first Antarctic expedition, with sixty Hamilton watches accompanying him and his crew. Seen here is an official watch from that expedition, powered by the Hamilton caliber 992.

Continued success

But Hamilton’s success was not limited to its association with Byrd. Indeed, the late ’20s and early ’30s saw the brand on a roll. In 1927, Hamilton watches also accompanied pilots on the first flight from California to Hawaii. In 1928, the brand released the Piping Rock, which would become one its most popular wristwatch designs. Its 14K solid yellow or white gold case had flexible lugs and a black enamel bezel with solid gold Roman numerals. When the New York Yankees won the World Series of baseball that year, Hamilton presented Piping Rock watches to all of the team members. Hamilton rounded out the 1920s with the purchase of the Illinois Watch Company for over $5,000,000.

In 1931, Hamilton introduced its patented Elinvar hairspring. The traditional steel hairsprings that had been used until then tended to suffer from changes in elasticity due to temperature. This could cause a watch to run slow on hot days and fast on cold days. The nickel-steel Elinvar alloy negated these effects and was both antimagnetic and virtually rustproof. This innovation showed Hamilton’s dedication to precision, allowing its watches to exceed railroad accuracy standards of the day (±30 seconds per week).

As commercial air travel became more popular in the early 1930s, Hamilton became the official timepiece provider for four of the United States’ major airlines — Eastern, TWA, Northwest, and United. Hamilton watches also made their silver-screen debut in the 1932 film Shanghai Express. The Piping Rock and the Flintridge models were worn by leading actors Marlene Dietrich and Clive Brook.

Hamilton watches of the 1930s

The Hamilton watches of the 1930s were very much inspired by the Art Deco movement. Applied Arabic numeral hour markers were a very common design trait at the time, and many watches featured rectangular or geometric cases. Of course, all were powered by Hamilton’s own calibers. Hamilton watches of the time were available in either platinum, solid gold, or gold-filled cases. As the Great Depression wore on, many people began to see solid gold watches as unnecessary luxuries. As such, less expensive gold-filled models were popular with consumers.

The timepieces of World War II

World War II began in 1939. Anticipating its eventual involvement in the conflict, the U.S. military put out requests to American watch manufacturers to provide accurate marine chronometers for its Navy ships. At the start of the war, the U.S. Navy had just under 400 ships. By the end of it, the Navy would claim nearly 7000 ships. Smaller ships needed at least one accurate marine chronometer, while larger ships required two or more. While Elgin and Hamilton both expressed interest, only Hamilton’s marine chronometers met the accuracy standards of ±1.55 seconds per day. It is said that Hamilton’s averaged half a second per day, making them the most accurate marine chronometers of the time. By the end of the war, Hamilton had supplied nearly 11,000 marine chronometers to the U.S. Armed Forces. These timepieces serve as inspiration for the modern-day Hamilton Khaki Navy Pioneer collection.

In 1942, Hamilton ceased the production of watches for civilians. Instead, the brand turned its complete focus to supplying the military. Throughout the war, Hamilton would deliver over one million military timepieces. In contrast to the solid gold models of prior decades, these military watches were much more utilitarian in nature. Many featured chrome-plated base metal cases, radium lume, and variations of caliber 987, Hamilton’s finest wristwatch movement. Pictured above are examples of the standard-issue wristwatch (left), the Army Ordnance Dept. watch (center), and the water-resistant canteen watch supplied to Navy demolition divers (right). Hamilton’s quality products and dedication to the cause earned the brand the Army-Navy “E” Award for excellence in production.

Halfway there…

Amazingly, this takes us only halfway through Hamilton’s long and, as you have read, storied history. The second half of Hamilton’s history was markedly different from its first, and we will be sure to cover it in due course. In the meantime, however, if you’ve enjoyed this article, please check out the other Hamilton reviews we have on Fratello and visit the official Hamilton website to learn more.