Tough Question: What Makes A Mechanical Watch Movement Good Or Bad?

The movement is one of the most crucial and costly parts of a mechanical watch. No wonder, then, that it is often used to judge a watch’s quality and value proposition. But aside from comparing watches with the same or similar movements, how do we judge them? Sometimes we go by proxies, such as “in-house or not,” decoration levels, or accuracy. But do those really tell you whether a watch movement is any good?

Debates about movements often end up in either anecdotal evidence (“Mine broke down” or “Mine never failed me”) or the spec sheet (“It runs at COSC spec” or “This deviation is unacceptable at this price”). Is there anything more substantiated we could say about a movement’s quality? Let’s have a look!

What constitutes a “good” movement?

I think it is important to start with some definitions. You can already see from the first two paragraphs above that it isn’t exactly clear what “good” even means here. There are, in fact, several different ways in which a watch movement can excel. And they don’t necessarily have to go hand in hand.

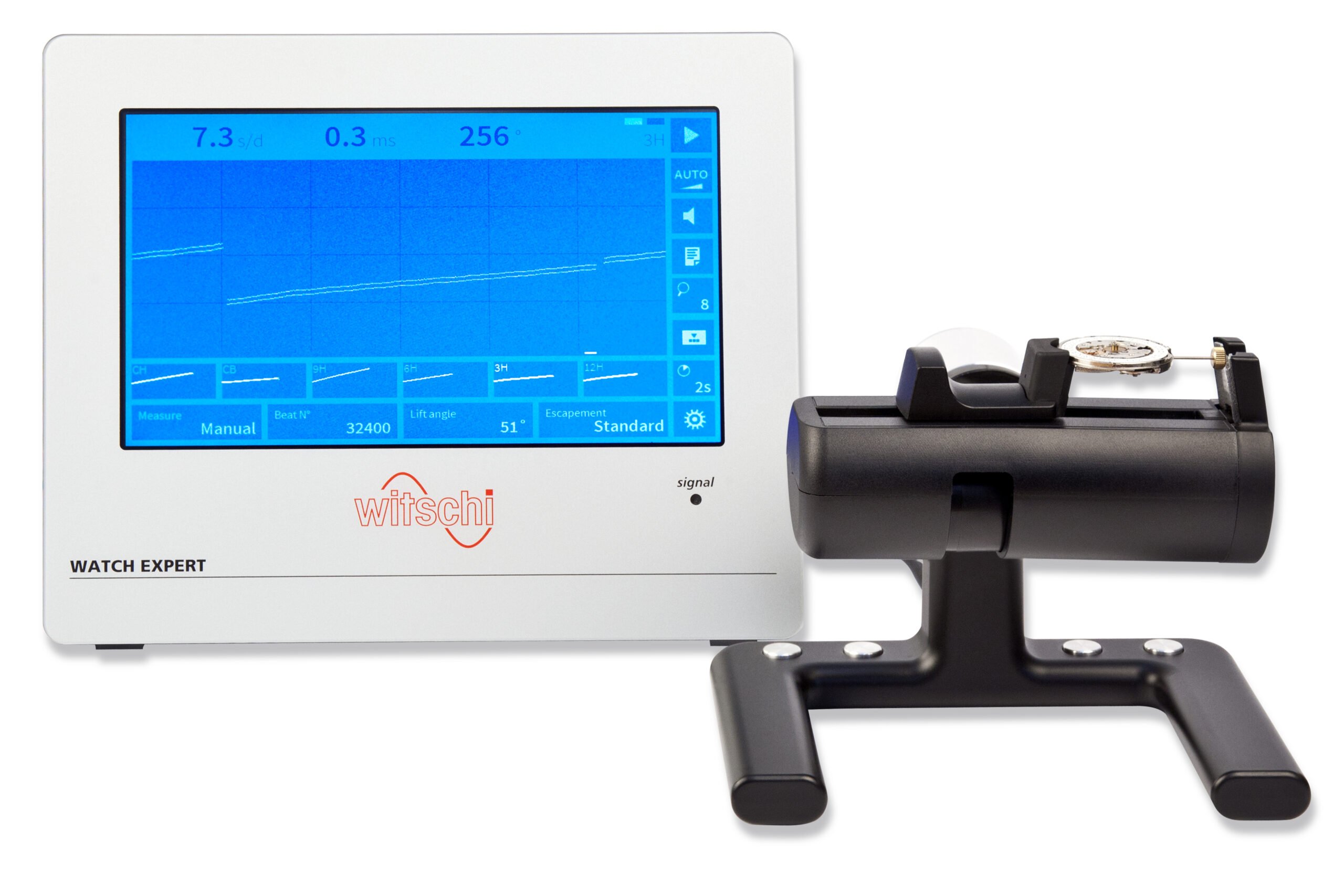

Let’s start with the obvious — specifications and chronometric performance. This is an easy one as you can read them on most brands’ websites. And you can test these claims with some basic equipment or a quick trip to your watchmaker. Arguably, chronometric performance is the core of it all. How well does a movement keep time, and how steadily does it perform? You already see things get a little more complicated here. One caliber can show amazing precision in five static positions. But one that scores lower on the timegrapher could outperform it in the rigors of real life. Resistance to temperature changes, movement, and shocks come into play. And, just as an example, how strongly does it react to depleting mainspring tension?

Since watches are now endlessly compared online, for many watch buyers, the spec sheet has become more important than ever. So you see a lot of effort made in upping the numbers. We have seen power reserves get longer and longer recently. What’s the result? A caliber with a 38-hour power reserve feels a bit outdated now. But unless you need a longer one for your specific lifestyle, it tells you nothing about the quality of the movement. I feel like a broken record player, but I will reiterate: specs matter much less than dwelling forums and social media might suggest.

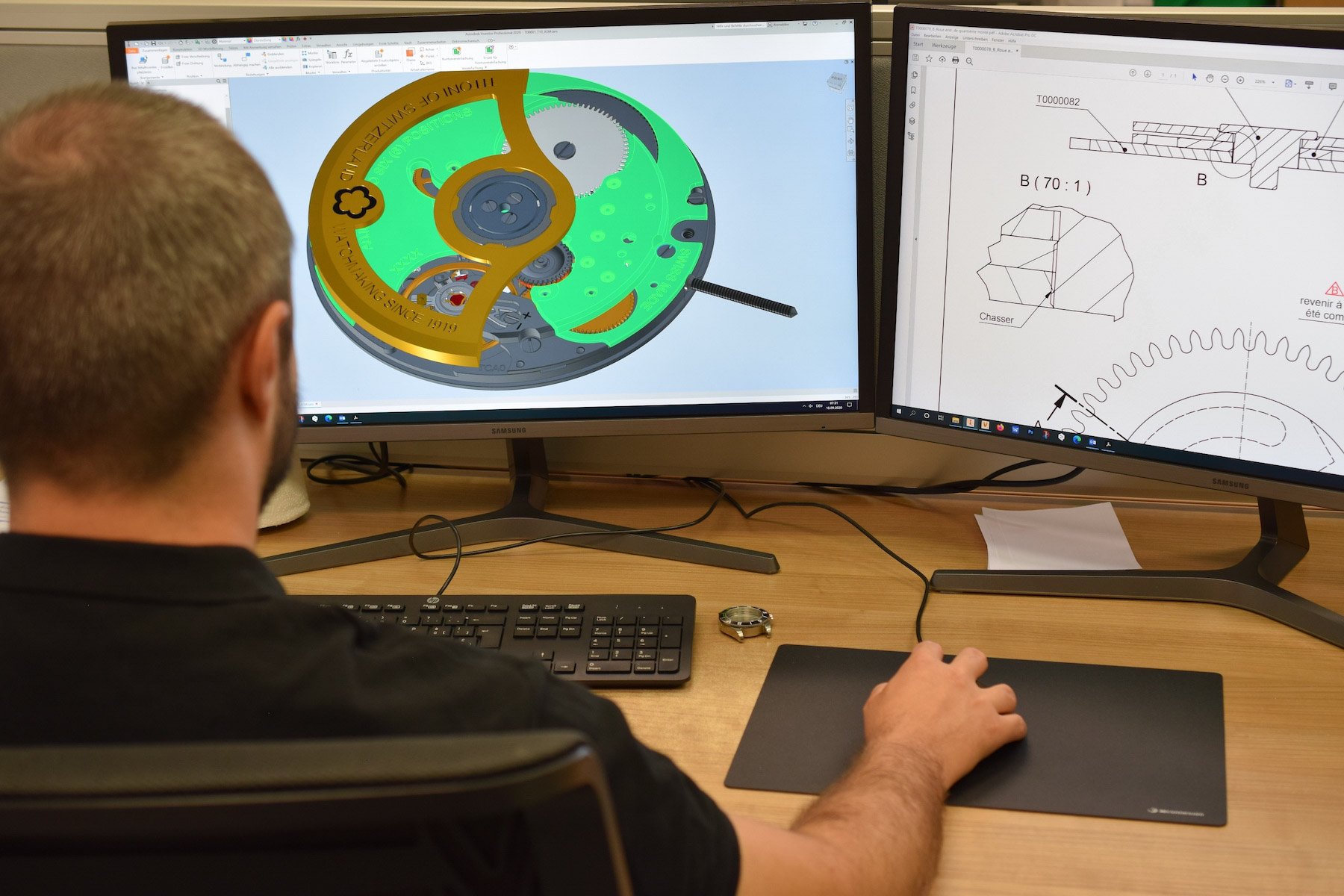

Architecture, materials, serviceability

Things get interesting when you dive into movement architecture. Great movement architecture can refer to a caliber that is built up in stages. When I asked my preferred watchmakers at Tempus about it, they mentioned Rolex. “It is extremely easy to take just the automatic works off or to remove the main barrel. This way, you can make very quick adjustments and targeted repairs,” they told me. “With their overall architecture, Rolex calibers make life very easy for the watchmaker.”

Then there is the use of materials. For example, you could build the same caliber out of two different alloys. One might definitively grind to a halt after five years while the other happily ticks for 20. The thickness of the materials matters as well. Tempus again refers to Rolex’s movements: “They are kind of like tractors. The materials and the thickness of the pinions, for instance, ensure that they just plow on.” On the other end of the spectrum, you find overly complicated movements. If removing a single plate means a bunch of spring-loaded parts fly all over your desk, it isn’t quite as elegant in design. It may serve its owner just as well, but from a watchmaker’s perspective, it is the inferior movement.

As you can imagine, all the above significantly impacts the serviceability of a watch movement. A caliber that is easier to disassemble/reassemble and has less wear on its parts is much easier to service. These qualities are to be expected from slightly higher-end calibers. Unfortunately, there is no way to tell for a layperson. So your best bet is to give your watchmaker a call to see if he/she has experience with the caliber you are considering.

The technical solutions that make a good watch movement

You likely know of several technical solutions in watch movements that affect quality. Think, for instance, of an amagnetic balance spring. Interestingly, the team at Tempus preferred the old-school steel springs as they could be tweaked by a skilled watchmaker. The modern silicon-based ones often cannot. I suggested that there may be some slight craftsman’s bias at play while the modern solution is superior for the watch’s owner. They chuckled and agreed.

“I love to see a Breguet overcoil and weighted screws in the balance wheel for adjustment,” says Mark from Tempus. This solution improves accuracy while reducing wear on the balance staff. When I asked the team about a double (full) balance bridge versus a single (half) bridge, the replies from the team were nuanced. “There is something to be said for both. The half-bridge provides a tiny extra bit of give under shocks. A full bridge is a little more solid and allows for adjustment on both sides.”

In terms of longevity, you would prefer a ball-bearing system for the automatic winding rotor over a bushing rotor. But, again, it isn’t as simple. The ball-bearing system distributes the weight of the rotor more evenly, reducing wear. A bushing, on the other hand, is simpler, quieter, and potentially more efficient. So, once again, it turns out to be tough to make hard claims about what constitutes a better movement.

Finishing a movement…and not just for looks

Finishing is another field that deserves dedicating some words to. Of course, aesthetics matter, especially under a display case back, so you would certainly be right to take looks into account when judging a caliber. I do love the old mindset of beautifully decorating a watch movement just for the sake of honor and for any potential watchmakers who might open the solid case back at some point. Today, luckily, we all get to enjoy these works of art.

But movement finishing has its mechanical relevance too. By removing sharp corners and finely finishing the edges and surfaces of all parts, you reduce the risk of parts damaging each other. You also reduce the risk of little burrs or shavings of metal getting into the moving works.

In terms of aesthetics, automated finishing has come a long way in more affordable calibers. You cannot beat the perlage, striping, engraving, and anglage of high-end hand-finished calibers though. If you look at a Breguet or Patek Philippe caliber, for instance, this is where a lot of its value resides.

So, what constitutes a good watch movement?

In short, there are several different ways to look at a watch movement’s quality. You can judge by features, precision, efficiency, architecture, materials, serviceability, finishing, and looks. And then you may want to look at external certification, availability of parts, and even long-term reputation. It all becomes a matter of personal preference here too. Whether you prioritize innovation or a proven track record will dramatically influence your evaluation, just to name one thing.

The one big downside is that a lot of the above is unknowable to the average consumer. So, at some point, you will have to take a manufacturer’s word for it.

I am curious to hear from you, Fratelli. What do you prioritize when judging a movement’s quality? And what currently unavailable information would you wish you had access to in the process? Let us know in the comments below!