How Watches Work: Fratello’s Guide To Watch Buckles And Clasps

Watch buckles and clasps can take many forms. In today’s market, we are truly spoiled for choice. For some brands, the quest to manufacture the “perfect clasp” is eternal. At times, it can seem as we horologically smitten enthusiasts will never guess what nifty buckle innovations lay just around the bend. As watch manufacturers strive to set themselves apart, buckles and clasps, once an afterthought in design, are now becoming ever more critical to a brand’s prestige.

For these brands, determining what makes the “perfect clasp” may not be as straightforward as one might imagine. The least we can do here at Fratello, however, is to make sure you understand your options and the styles available today. If you know not only what types there are, but also the proper terminology, you can make more informed decisions when considering your next purchase. With that in mind, we thought we’d assemble this handy-dandy guide to buckles and clasps. Though I’m always unreasonably terrified I’ll leave something out, I think I’ve done a pretty decent job at assembling the information we’ll need to make the most educated decisions. I hope you’ll enjoy it!

Tang/pin buckles

Before wristwatches with metal bracelets were “a thing,” leather straps were the order of the day. And if you think about it, what are leather straps, really, if not miniature belts? In fact, here in Japan, watch straps are even called “beruto,” the Japanese pronunciation of “belt”. Therefore, even to this day, the most common type of closure for leather, rubber, and textile straps is the “belt-style” tang buckle.

A tang buckle is pretty straightforward. It is typically made up of a square or angled metal piece that is open on one end, a spring bar or screw to close it off, and a pin, or “tang,” which connects to that spring bar or screw. The tang fits in a notch cut into the shorter end of the strap, and the spring bar/screw holds it in place. Attach the open-ended piece to the bar, and voila — you have yourself a no-nonsense, time-tested buckle. The long end of the strap simply feeds through the buckle, and the tang pokes through a hole in the underside of the strap to close it.

Some buckles even feature double tangs, like the one on the Hamilton Khaki Field. While I don’t think two tangs provide any additional security, I must admit, they do look cool. In this case, the tangs form the “Hamilton H”, which is a nice stylistic touch. Personally, I’m still waiting on a Wu-Tang buckle, but maybe that’s just me.

Single-fold/deployant clasps for straps

Both “single-fold” and “deployant” are interchangeable terms. In some countries, a deployant clasp is even referred to as a “deployment” clasp. We’ll save the discussion/debate about this semantic technicality for another day. For now, suffice it to say that you’ll see all of these names in popular usage. This clasp was designed and patented by Louis Cartier in 1909. It made its debut on the leather-strapped Cartier Santos in 1911. A deployant clasp for a strap is typically made up of two curved metal pieces that are connected with a hinge. The top piece folds onto the other, their curves complementing each other like spooning soulmates.

Variations in design

Designs vary widely from brand to brand. The most common type, however, as seen on the IWC Big Pilot above, features an open bracket at the end of one of the curved pieces. This connects to the shorter end of the strap with a spring bar. On the other piece is a buckle, similar in shape to a tang buckle. This connects to the longer end of the strap with a pin. The pin pushes down through the holes on the top side of the strap. With this design, the longer end of the strap usually lays on the outermost part of the wrist and is held down with keepers. This gives it a no-nonsense, utilitarian look.

Other single-fold clasps allow the longer end of the strap to tuck under the shorter end when closed. This results in a cleaner, more refined look. As seen on the Cartier Pasha above, the pin that connects to the strap is not on the buckle itself but rather, attached to a separate piece on a bracket. This connects to the strap from underneath. In the past, Cartier also used a friction system that let the longer end of the strap fold under itself. Some manufacturers, still use that design today. As you can see, the buckle of this Cartier features pushbuttons. Pressing both of the buttons allows the clasp to open easily when you want it to, while not pressing them keeps the clasp more secure than a simple friction fit would.

Some watches, like the Oris ProPilot above, even use a design with a locking flap. As indicated on this buckle itself, one must simply lift the flap to open the clasp. This utilitarian yet svelte design that I’ve not noticed other brands use.

Single-fold/deployant clasps for metal bracelets

The deployant clasp is also very common on watches with metal bracelets, and there are many variations of it. We can see a basic version of the deployant clasp on the vintage Rolex Datejust above. It simply connects to both ends of the bracelet with spring bars and closes with a friction fit. Because the bracelet links are removable, the wearer doesn’t have to deal with any excess material. This particular clasp has visible holes for micro-adjustments as well. Generally, one would leave more links at that end of the bracelet, allowing for better adjustability.

Many modern single-fold clasps for metal bracelets feature sophisticated micro-adjustment systems. An enthusiast-favorite is the Tudor Pelagos clasp pictured here. This design does away with visible micro-adjustment holes, opting instead for three notches machined into the inner walls of the buckle. These allow for three micro-adjustable locked positions. In addition, two springs inside the clasp allow the bracelet to expand and contract freely outside of the locked positions. The clasp also features a folding extension for fitting the watch over a wetsuit, shirt, or jacket cuff.

Pushbuttons

Some deployant clasps feature pushbuttons, like the Oris Divers Sixty-Five above. As on deployant clasps for leather straps, these buttons provide additional security when on the wrist. Because the wearer must push both buttons to open the clasp, the buttons greatly reduce the risk of the watch popping open and falling off. The buttons also allow for easy-opening when taking the watch off. This particular clasp also features visible holes for micro-adjustments.

This Grand Seiko SBGJ249 features another version of a deployant clasp with push buttons. This clasp, while providing a cleaner, more integrated outward appearance, lacks any type of micro-adjustments. Typically seen on dressier watches, bracelets with this type of clasp usually rely on half-links for a more precise fit.

Flip-locks

Many dive/sport watches, like the Wempe Iron Walker, feature a deployant clasp with a flip-lock for added safety. As the name suggests, one must first flip the lock in order to open the clasp itself. This is a rugged, reliable solution that has been in use for decades. Some modern flip-lock deployant clasps, like those on modern Tudor watches, even feature ceramic ball bearings that mitigate the long-term effects of opening and closing it.

The ultimate in security

For those who are either extremely active or extremely paranoid, watches like the Grand Seiko SBGH255 offer the pinnacle of security in wristwatch clasps. Yes, deployant clasps like these feature both pushbuttons and a flip-lock. With features like these, witnessing this bracelet pop open accidentally would be tantamount to spotting Bigfoot in a porta-potty.

The super-seamless crown lock

Last up on the list is of single-fold clasps is a deployant buckle so camouflaged you’ll hardly notice it’s there — the Rolex “crown lock” clasp. You can find these on Rolex “President” and “Super Jubilee” bracelets. They open by simply lifting up on the prongs of the Rolex coronet. While older versions had a friction-fit closure, these days, there is a hinged lock that ensures the clasp stays securely shut. The design is meant to offer a nearly seamless aesthetic to the bracelet.

Double-fold, dual-deployant, or butterfly clasps for straps

These three terms are used interchangeably (along with, you guessed it, “dual-deployment”). As the name suggests, these clasps feature two folding pieces instead of one. In general, these pieces each fold into the center of the long, curved piece closest to the wrist. The longer end of the strap weaves into a buckle, secured with a pin on top or a tang underneath. While the short end of the strap is usually fastened to an open-ended bracket with a spring bar, the Zenith Captain above uses a double-headed screw. The most basic dual-deployant clasps have no pushbuttons.

Some dual-deployant clasps for straps do feature pushbuttons, as seen above. Like their button-equipped, single-fold counterparts, these clasps are more secure because the user must press both buttons to open them. Regardless of whether they have pushbuttons or not, most dual-deployant clasps require the long end of the strap to lay on top of the short end. I have yet to see a dual-deployant clasp that allows the long end of the strap to tuck underneath, though one may (and hopefully does) exist.

This Corum Bubble Divebomber has a dual-deployant pushbutton clasp with micro-adjustments. On this watch, the ends of the strap are likely the same length, and one must hope that the micro-adjustment holes will allow a snug fit.

Some watches with rubber straps and dual-deployant clasps, such as the Patek Philippe Aquanaut, require the strap to be cut to size. While this provides an incredibly clean look, many collectors don’t particularly enjoy cutting straps. As they say, “Measure twice, cut once,” or else!

Dual-deployant clasps for metal bracelets

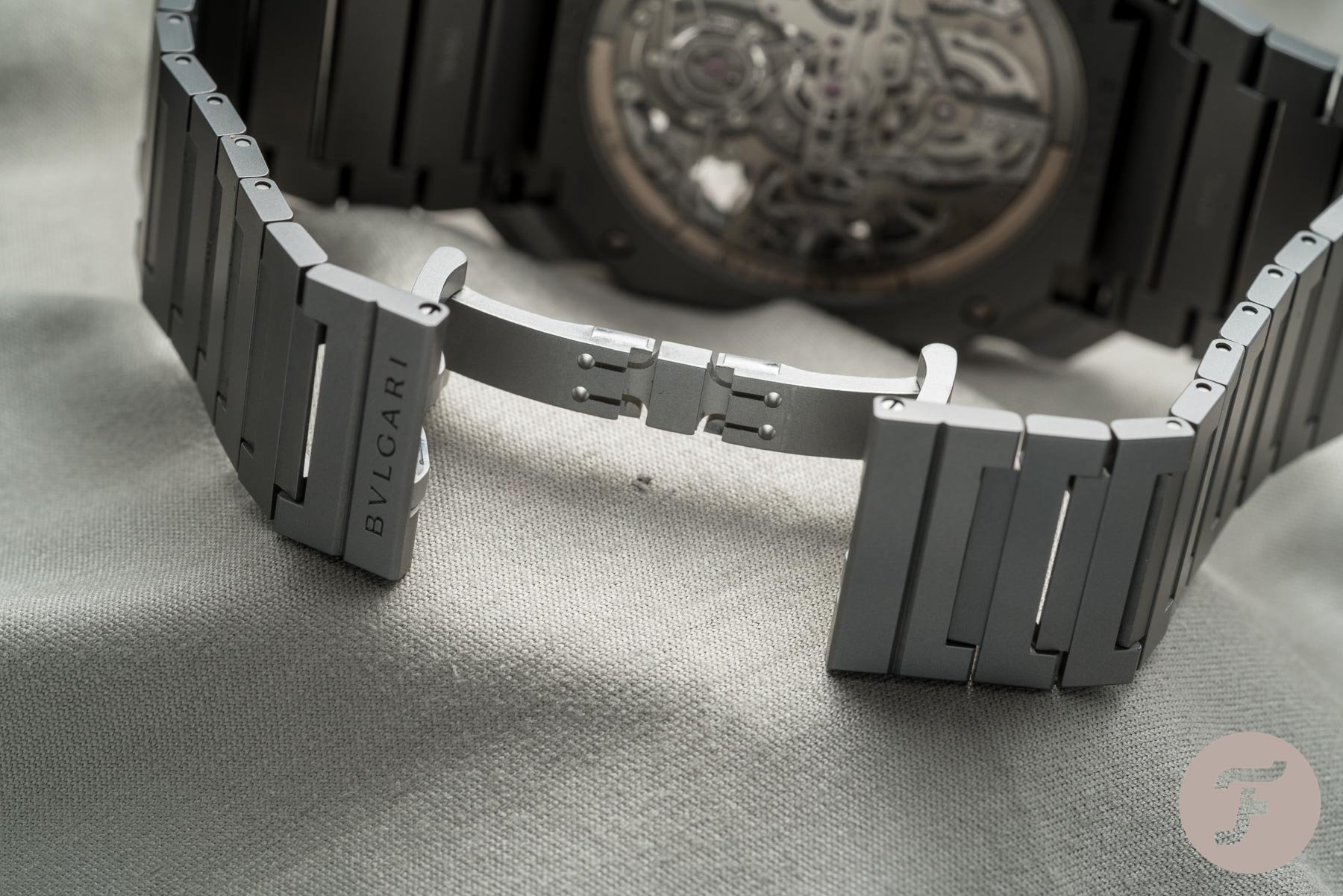

These clasps are the go-to choice for many luxury watchmakers, and it’s easy to see why. Dual-deployant clasps for bracelets are able to maintain an incredibly low profile on the wrist. Depending on their design, some even integrate almost seamlessly into the links of the bracelet. The Bvlgari Octo Finissimo Tourbillon above has no pushbuttons. While perhaps not as convenient to open, this design provides the cleanest look possible.

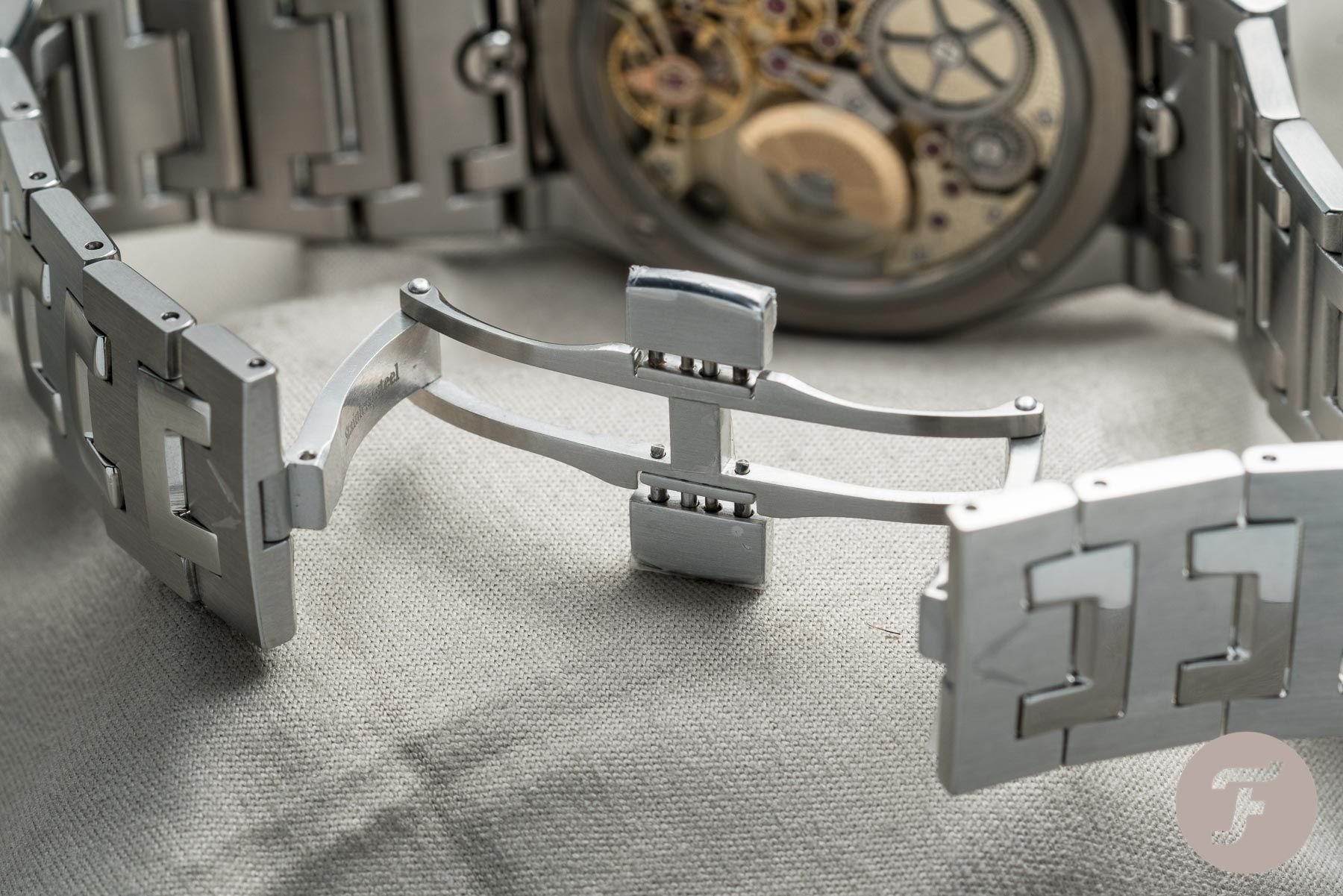

As you could probably guess, dual-deployant clasps for bracelets can also come with pushbuttons. The Czapek Antarctique here is a beautiful example of this. While the buttons protrude slightly on either side of the bracelet, opening a clasp like this is generally much easier than opening one without buttons.

Hook clasps for textile straps

Hooks clasps are seen a lot these days on “Marine Nationale” straps. Though these have exploded in popularity in recent years, the design was originally used in the 1960s and ’70s by divers in the French navy. Straps like these, seen on the Oris Carl Brashear Limited Edition above, are usually made of elastic cord. They use a unique clasp that I have yet to see on any other type of strap, with a dramatically curved hook that latches onto a keeper. I have never owned or used one of these straps, so I cannot personally attest to their security on the wrist. But hey, if they’re good enough for divers in the French military, they’re probably just fine for a lazy bum like me.

Hook clasps for mesh bracelets

You can find both single and dual-deployant clasps on many mesh bracelets, particularly on the higher end of the market. Hook clasps, however, are also very common, and in my opinion, an excellent choice. As seen on the mesh Meccaniche Veneziani bracelet above, the longer end has a clamp that can snap down anywhere on the bracelet. This allows for practically infinite adjustability. The clamp is fitted with a bar to catch the hook on the shorter end of the bracelet. Since this hook is not as dramatically curved as the ones on Marine Nationale straps, there is usually an additional flap above it, which locks down onto the clamp on the other side. Most on the market today also feature a flip-lock for added security.

Why am I such a huge fan of these clasps? Well, I mentioned their infinite adjustability, and that is a huge factor. Clasps like these don’t restrain my choices to intervals pre-determined by the manufacturer. These clasps also allow the longer end of the strap to slide under the short end, giving it an extremely clean look. The additional thickness that the clasp adds to the bracelet is not too annoying, and being only about a centimeter long, the clasp itself doesn’t take up much space on the underside of the wrist. While these clasps are generally found on mesh bracelets on the lower end of the market, I would love to see someone refine the design even more and put it on a luxury mesh bracelet.

Rare-but-honorable mentions — “seatbelt” and jewelry clasps

These last two aren’t seen very often these days, but for the sake of being thorough, I’m going to throw them in for good measure. The “seatbelt” clasp, as seen on the vintage Omega Ploprof above, works exactly as the perhaps unofficial name suggests — like a seatbelt buckle! One end of the strap has a “male” connector, as we said in the hardware business, which locks into a “female” connector on the other side. To release the strap, one simply needs to pull up on the tab on the female end. This clasp also features visible holes for making micro-adjustments.

The jewelry clasp, as seen on the vintage Chopard Happy Diamonds above, is not a common feature in men’s watches. Nevertheless, I would be remiss not to mention it. After all, wristwatches didn’t start out as rugged and “manly” as they are today. For decades, in fact, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they were known as “wristlets” and strictly relegated to a woman’s wardrobe of jewelry. Using a design commonly found in jewelry bracelets, these clasps feature a buckle that locks around a bracket and pin. While some jewelry clasps have just one folding flap, the Chopard clasp in this photo features an intermediate arm on its buckle. This is a three-position micro-adjustment of sorts, which locks the pin between it and the upper flap. Once closed, both of these pieces snap down onto the innermost piece.

That’s a wrap!

So, did I miss any? That question is probably bound to open a whole new can of worms. The more astute Fratelli among us will most likely find some obscure contraption that I left out. Nevertheless, I hope this guide to watch buckles and clasps has been helpful, informative, and even possibly entertaining!

What is your favorite type of clasp? Who makes the “best” one on the market? Let us know in the comments below. As always, thank you for reading, and may you continue to open and close your clasps in good health!

(Is that a thing?)