Watches for the Long (Over)Haul: Comparing New Service Intervals Of Rolex, Oris, Casio, And More

Haute horology used to be simple. Assessing the quality of a watch generally came down to its ability to keep time. In those days, the concept of a specialized “tool watch” was somewhat alien, as all watches were, more or less, tools. The wire-lug-welded behemoths of World War One and the made-for-combat fliegers and infantry watches of WWII seemed to shine a light on the necessity of accurate timekeeping in a way that hadn’t been so keenly appreciated since Harrison’s experiments in marine chronometry, but it was the release of the Rolex Oyster case (in between those two global conflicts) that really set the world on the path toward change…

Released in 1926, proudly touted as the first dustproof and waterproof hermetically sealed watch, the Oyster case made history when it swam across the English Chanel in 1927 around the neck of one Mercedes Gleitze, emerging on the other side unscathed and in perfect working order.

The flood gates were opened, so to speak, and the race to develop watches capable of going anywhere we might try to put our bodies was on with a vengeance. The middle of the century was an age of exploration. Job-applicable movement complications, rotating bezels, and pressure resistance ratings became the measurements of merit for the pieces that were to explore the depths of the ocean and the reaches of outer space.

A new wrench

The conversations about which watch was “better” had now become muddied by the advent of an entirely different scale. Most people concerned with the ephemeral quality of watches maintained sanity by keeping the categories separate in their minds: tool watches stayed “over there” with the mental hierarchy of wrenches and the like. But in 1969, with the release of Seiko’s Astron, the first quartz-powered watch available on the mass market, and the introduction of the argument of whether pristine mechanics or precision timekeeping made for a better watch, the whole fragile logic of watch quality went up in smoke.

(please don’t mention Spring Drives)…

Since then, a lot has changed. Computers have become smaller and more watch-like. Watches have incorporated radio reception for atomic timekeeping. Truly, it amazes me that we still have an intuitive working definition of “watch”. But things have shaken out to an extent: there are commonly accepted lines in the sand demarcating the classic mechanical watches (please don’t mention Spring Drives), and all those others. And within mechanical watches, one steady aspect that seemed mostly off the table for discussion because of its ubiquitousness was the lowly and unassuming service interval: three to five years almost across the board. But I, harbinger of chaos, am here to tell you that this is no longer the case, to our collective benefit.

Chaos unleashed

Rolex, ever the champion of calculated incrementalism, had long been touted as the watch that could be worn perpetually, beyond even the aims of their Perpetual Oyster. Much to the chagrin of many a watchmaker (mine confided in me, unprovoked, his pain of receiving a neglected Rolex; I don’t even own one), the longstanding, mistaken understanding of a type of Rolex owner was that the watch could run just about forever without servicing.

…Rolex ticks everyone else under the table.

Let me clear: this is completely false. As robust as a Datejust may be, no one from Rolex has ever suggested that the brand’s watches could go on indefinitely without servicing. But the proof is in the pudding. There are neglectful watch owners of every brand, over the decades these scientists of apathy and procrastination have been reporting their results: the Rolex ticks everyone else under the table. The more moderate of envelope pushers found that an Explorer and the like would fare just fine (without scolding from their local watchmaker) getting serviced every 10 years.

A rare bit of audience feedback

Well, Rolex recently (and quietly) officially updated its recommended service interval to 10 years. The brand added this caveat: “depending on the model and real-life usage.” Some speculated that this was in tandem with the brand’s most recent caliber releases. Those using either “Siloxi” (silicon) or “Parachrom” (niobium and zirconium alloy) hairsprings, certainly seem less likely to need servicing. However, the recommendation is a blanket statement extending to all models. This move confirms what Rolex owners already “knew”. While the watches are still covered by a five-year warranty only, I’m not sure anyone is balking given Rolex’s track record on reliability.

Rolex may see a handful of extra-worn watches…

This move by Rolex may have in fact been a partial gamble. I expect the Crown is anticipating receiving older models with movements that are now more worn and require more attention. I believe putting a conditional blanket statement on a 10-year service interval is one part brand imaging and one part nod towards the brand’s investment in novel materials and engineering. Rolex may see a handful of extra-worn watches that perhaps should not have gone the full 10 years (though who’s saying any Rolex can’t?) but this tactic may help sell more of the modern available models that can certainly go 10 years without a problem.

Furthermore, and rather simply, it reduces the volume of services coming into the factory by, one can assume, at least half. That’s not to be slept on. Very few after-sales operations run at a profit. Despite scarily high service costs, the processes involved in servicing a watch behind the scenes are vast.

“Luxury workhorse” movements

Rolex aside, with the brand’s anomalous successes and “luxury workhorse” movements, most of the mechanical watch industry has relied entirely on bought-in calibers for the past half-century. This stagnation of innovation, having only survived quartz and the smartwatch/cellphone uprising thanks to Swatch’s masterful reinvention of what a watch could be, solidified the common 3–5 year service interval.

Pushing the boundaries

A couple of brands have stretched the capabilities of these vintage engines to their limits. Sinn has been one to really to push the envelope in unique casing technologies and alterations to standard historic movements, and the brand earns a solid honorable mention among the 10-year bruisers. Their DIAPAL technology (an acronym for diamond pallet), combined with inert gas filling the case and copper sulfate de-humidifying capsules make for some seemingly bomb-proof watches that push the resistance to friction and corrosion to the maximum. Currently, their manufacturer’s recommendation for the DIAPAL models is an impressive seven years, which is the best I’ve come across with “standard” movements.

Really, it has only been the discovery and development of new materials — silicon primarily — and the application of such that has made the jump to next-generation mechanical movements possible and subsequently increased service intervals. Every year we see new applications and improvements with silicon and new surface treatments that blow our minds. Some of the most recent? The pulsing silicon oscillators of Zenith’s Defy Labs took my breath away before seeing the same principles miniaturized further in a Frederique Constant of all things. Silicon’s properties make it an ideal material for mechanical watches: it’s friction resistant, holds its shape, can be manufactured to precise tolerances of shape and elasticity and is not affected by magnetic fields.

Silicon finally accepted

Watchmakers have spent the last decade or so beginning to incorporate silicon into their movements. While it almost feels like old hat now, it is quite possible we are only just seeing the beginning of the silicon revolution. Really, the sky is the limit. But as the use of silicon is redefining the mechanics of mechanical movements, we are seeing a necessary (and welcome) departure from the incremental developments of the 20th-century calibers.

A new player?

One such company to wholeheartedly (and perhaps unexpectedly) embrace silicon and come onto the scene with an entire novel caliber is Oris, the (now perhaps not so) scrappy independent Swiss watchmaker holding its own and increasing market visibility among titans and conglomerates. Released in October 2020, Oris’s Caliber 400 (and now 401) have established a high bar for other manufactures to meet. Calibers 400 and 401, found in their new Caliber 400 Aquis and latest Carl Brashear Limited Edition, respectively, are entirely new movements designed from the ground up.

There’s a wonderful technical review of the Calibre 400 here for those interested in a deeper dive into the specifics, but regardless of what the watchmakers think, Oris is putting its money where its mouth is with a 10-year warranty accompanying its 10-year suggested service interval, which I believe is an industry first. Add that to the anti-magnetism and a 5-day power reserve, all tucked away in an industrially honest-looking caliber, and I believe we have an absolute winner.

At $3,500 USD for the bracelet version of the Aquis Date Calibre 400 with the specs mentioned above, I can’t imagine how Oris won’t quickly become the darling of the pragmatically minded watch wearers if it isn’t already, especially as it releases more models utilizing the Calibre 400’s architecture. I believe history will smile fondly upon this milestone in Oris’s story.

The “shrug equation”

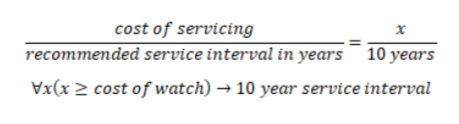

But I know not everyone can afford or even wants a Rolex or Oris. To rank the quality of a watch by its service interval is certainly a perspective of economic efficiency, and to this, I say there are more affordable options. For this we turn not to a specific brand able to guarantee a 10-year service interval for sub-$1000; the wizardry already exhibited by Oris is already extraordinary. Instead, we look at mathematics, and a little formula I like to call the “shrug equation”. I’ll keep this simple for those of you already glazing over from the trauma of calculus class, but it looks like this:

Any actual mathematicians please excuse my fouling and possibly incorrect use of symbols. But it boils down to this: if the number you get by dividing the full-service cost for your watch by the recommended service interval multiplied by 10 is greater than the cost of the watch, you are green-lit for making the decision to wait 10 years to service said watch.

A working example

We can use a Seiko Prospex Alpinist as an example. The SPB119 will be our model for this exercise. With a 2–3 year service interval recommendation from Seiko (we’ll go with 3) and a service cost of $260 (not including taxes or shipping and handling) for 6Rxx movement equipped models (the 6R35 is in the Alpinist) we get an “x” value of $866.67. Now, the SPB119 retails at $725 from seikousa.com, less than “x”, passing the shrug equation. That is to say: after 10 years of servicing this watch religiously per Seiko’s recommendation, you could outright purchase another one brand new for less money spent.

Now, the shrug equation takes some factors for granted. One, that there’s no emotional or other attachment to the watch itself. It assumes a nonchalance on the owner’s part that they’d be just fine with the watch catastrophically failing before reaching its 10-year servicing date. Also, it assumes that the same watch would be available for purchase at the same price any time during the 10-years.

We know that to not be the case, historically. But assuming the watch is salvageable upon a potential failure and one is fine with that happening, the argument could be made that a watch that passes the shrug equation might better suit the owner only being serviced every ten years. In truth, with entry grade workhorse calibers the cost of replacement can be less than the man-hours needed for proper servicing. And there is plenty of anecdotal evidence out there on the forums of owners of sub-$1000 watches perfectly willing to take the 10-year challenge (and beyond) and appear to have come out on top. Of course, you risk causing a disappointing slow shake of the head from whatever watchmaker does eventually crack the case-back off, but I find watchmakers are generally the contemplative, somber sort to begin with, so it may not be helped regardless.

Turning to Casio…

I know there is a handful of you reading this thinking I’ve forgotten the ultimate watch with a 10-year service interval. Well, I like to save the best for last. Like I said previously, length of service interval is a prudent characteristic to judge a watch upon, and there are many out there that would think even the almost $1000 for twenty years of a Seiko Alpinist with one servicing at the halfway point is much too much to spend; prudent indeed. The Casio A158WA-1, I would posit “The” Casio, with module No. 1271 (an important distinction) proudly advertises a 10-year battery. Sure, it’s a quartz, and it’s only marked “water resist” so there are no seals but hey, on the plus side, there are no seals to service!

With an alarm, a stopwatch, and a backlight available at the push of a button, it has functionally beyond any watch I’ve mentioned thus far. And in the spirit of the shrug equation, at about $20 a piece, it’s perpetually replaceable (water resistance be damned!). I know a medical professional that wore one working in the rigors of the hospital until the screen was so scratched it could only he could decipher the time…

This special Casio A-158W actually has a shorter projected lifespan than the models referenced. Do you know how long it is and why?

Capable limits

Harkening back to the intro of this article, a “tool” watch can only be as capable up to the level it is ever required to be, meaning: 20 bar is wasted on the terrestrial. A basic Casio can be worn to shreds with no pain or problem for one’s wallet. I’ve tried to do just that to mine but it’s a couple of years past the 10-year mark and it’s still “ticking”, as it were. I have that $10 ready for when it does finally need a battery.

Quartz and shrugs aside, I think one of the most exciting things to come from the watch industry in recent years is this step towards the long-lived watch. In my mind, it elevates the watch from an anachronistic trinket (which I love) to a dependable tool. The Haute Horlogerie of yore that lives on today is as pertinent as it’s ever been.

We should still delight in the finesse and exceptionalism that only comes from hand finishing and grand complications. The pinnacles of watchmaking are ever pulling us into the future of what is good, beautiful, and true. But Platonic ideals are dead, and it is now up to the individual to determine what their personal pinnacles may be. For me, it has something to do with honest utility independent of anything but itself, with the je ne sais quoi that is achieved by efficient design. The 10-year mechanical wristwatch takes another step towards that, and I look forward to where it may go. The day they make a watch that can tick forever is the day I can rest.